Whether it is a door wearing gloves, a painting of a man hanging laundry made of fabric or a performance thatching window frames together to make Louise Bourgeois-like cells, to speak about artist Devin N. Morris’s work it’s best to talk about distinct characters.

You can start with the ones that informed him back in his hometown of Baltimore: his mother, his grandmother Betty and her husband, his grandfather Nate (“who everyone wanted to be when they grew up”), Grandma Carol; and then move onto the ones that Morris actively chooses to keep walking alongside like fellow artists serpentwithfeet and Campbell Addy. But what most people dawdle on, to Morris’s chagrin, is guessing the origins of the figures that appear in his sculptural paintings because, “I prefer to talk more specifically about the how than the what,” Morris says. The “how,” as Morris has taught me, is where you find the most important characters. In lieu of a step-by-step, Morris’s process could be depicted as a cast of archetypes, whose personalities are summoned for different perspectives. “I have to take on roles to make the art,” he says.

The Predator

“The predator is the one who goes out and seeks vulnerable objects in neighborhoods that then become materiality,” Morris says. “The predator found a gate here.” Morris is in the Brazilian countryside, two hours from Rio de Janeiro tidying off a two-month residency at Residencia São João. It’s his second time after almost a decade ago when he dragged a damaged palm tree back and wrote a poem about it. “This time was more of a cleansing than a rediscovery,” he says. Morris made the decision this winter to pack up the studio and be nomadic for a little while. Let the predator drive. “The way that I had been deriving attachments to space was coming from a lack of perspective as opposed to abundance,” he says. “In my twenties, I had such an improper foundation. It was built not in the image of my own theory or my own practice, but my survival.” The Brooklyn home he tucked away in a decade ago is now too small for him, yet the city kept haunting him during his first weeks in Brazil—like an anxious ex. “I’ve been drawing graduation hats and burning gates, thinking about this false narrative of New York being filled with gatekeepers,” Morris says. “To me, that gate is typically of the mind and not necessarily of the expectation or the physical.”

The Salon

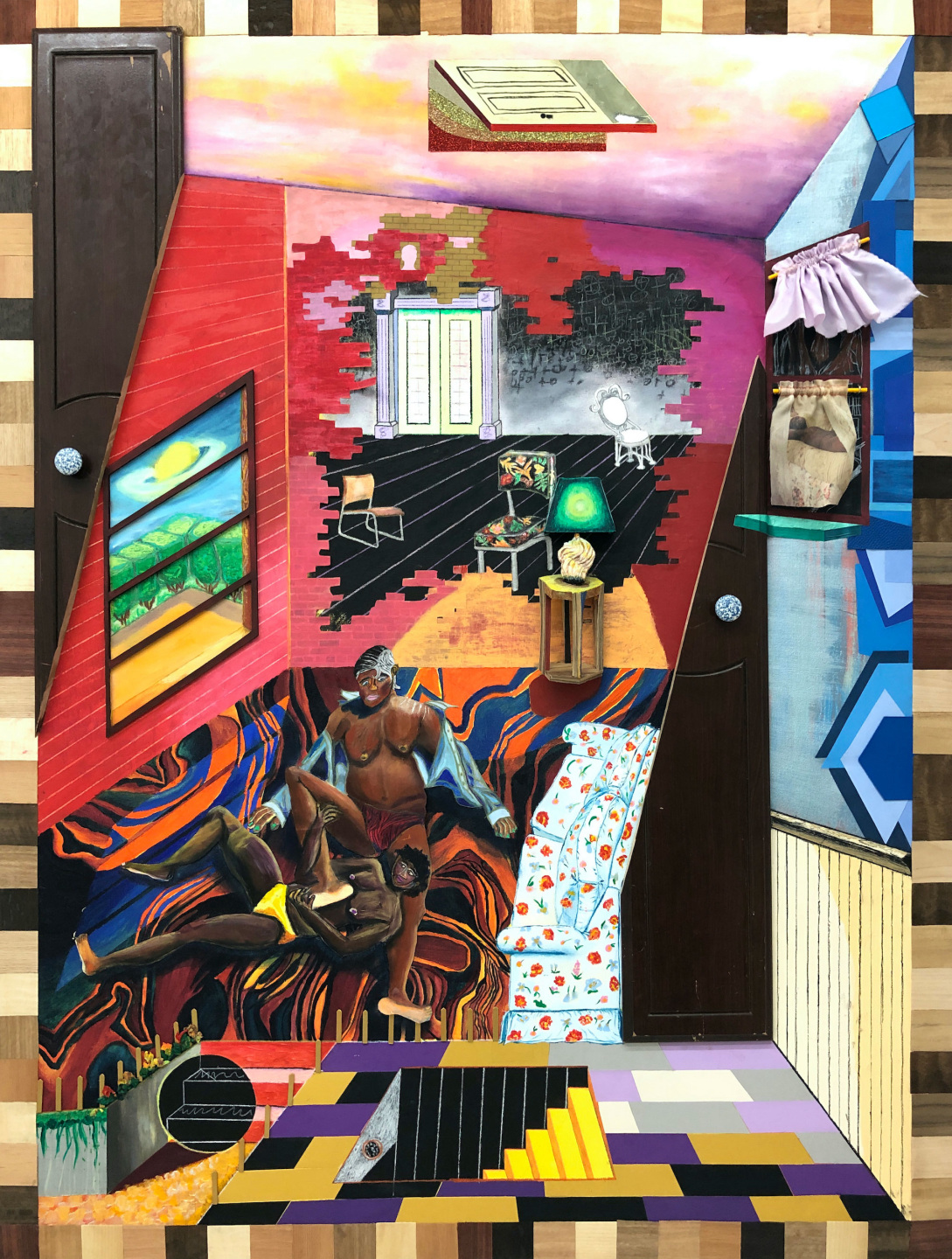

Morris spells fashion with a capital F. “I only want to go to New York for fittings,” he wrote in his diary recently. In the last of his teenage years, in the alleyways of Baltimore, he dreamed about fashion as a way to tell his stories. “Color, presentation, expectation and the histories of costume are always present a little bit for me,” Morris tells me about his native tongue. “My studio is an atelier.” Each work is a new client in need of dressing even if that client is a door or a gate—it often is. “When I take a door and dress it, I’m literally trying to deal with how space and presentation of the body is so inherent and interconnected,” he says. The metaphorical atelier extends to all materials in the studio. If you see the same found fabric or wood veneer pop up in different works again and again, it’s because they are part of the same collection, one that isn’t finished until the material runs out. Morris once dated a fashion designer and came home to cut-outs of sleeves, pant legs and torsos laid out on the kitchen table. Pattern-making has always captured his affections because Morris is a quilter at heart. Everything he makes is a quilt. Even his most esoteric performances are given their form by a rigorous ritual of dismantling and mending. “There’s an overall energy of Black women’s knowledge that is everything,” Morris says. “Everything I learned is from the quilt, because my work is based on the poetry of collage (utilize what you have to make what you need).”

The Publisher

3 Dot Zine, Morris’s independent art magazine, catapulted the artist into microcelebrity before his paintings ever did. The magazine hosted salons—which Morris simultaneously curated, hosted and documented. “It was definitely a wonderful space for the Black L.G.B.Q.T. folks,” says musician and Morris’s confidant serpentwithfeet who used to attend 3 Dot events. “3 Dot Zine always felt like a circle where everybody was part of that process. Devin was collaging the conversations that were being had. He has a way of making everyone feel special and that’s what I think about when I think of 3 Dot days, just how alive those spaces felt, how he helped build community. We were all, all young Black artists on the come up, you know, and it was just great to sort of build with them in these spaces.”

I remember 3 Dot as an anchor for the Bushwick Art Book and Zine Fair at Signal gallery in 2015. But in recent years, Morris, too burnt out on the media circuit, is turning his attention towards more personal projects. In the mythology of Morris, the zine-maker is a tragic figure because it represents the time the artist first encountered scarcity, the art world’s false prophet. “[Financial realities] veered me off the wanting to produce zines, I want to be able to pay everyone,” he says. “I needed to think about what that looked like, and then also make money to be able to publish other people.”

Serpentwithfeet offers another way of looking at it: “The sign of great work is if you can really pour, if you can spill on the page or the canvas or the stage. Perhaps when Devin is being private it is his way of preserving that for the canvas or for whatever medium he’s working with. It’s letting the tank fill up.” These days Morris has been saving the tank for painting but he foresees a return on different terms. The magazine, as a format, lends itself organically to a material practice rooted in collage. “If you come and work with me or 3 Dot on a publication, we are making an emotional object that is strong, smart, interesting and distinctly for you,” Morris says. “When I was doing all that 3 Dot stuff, [the collaborations] were fully based on my friendships at the time, and now the goal is, ‘What does 3 Dot Zine for Devin look like?’”

Morris sees a return to publishing as inevitable. The right opportunity hasn’t hit yet, but the foundation work is done. “Now that I’m moving from a place of self-agency, it is going to be so easy for me to edit in the way that I know myself to be an editor,” he says. In the meantime, Morris is thinking about one of his earliest catalysts, the late fashion editor and creative director André Leon Talley, more than ever. “Growing up, reading André Leon Talley in Vogue, reading his books in high school, reading about the Gucci family, those things made me want to be opinionated,” Morris says. “That was the first gift to me as an artist, these opinionmakers, these statement people, statement objects.”

The Editor

“I’ve always wanted to be the editor. When I’m at the studio, it’s like: ‘Are we doing that? Are we doing this?’ I’ll grab a door and hold it up to the piece-in-progress and ask: ‘Is this it?’ The elegance is what attracts me to some objects. For instance, this iron gate is gorgeous, it’s gorgeous. It reminds you of a solid sturdy home that doesn’t exist, that will never be built again.”

The Caretaker

At home, there is no women’s work, there is no men’s work—it is just care work. Morris learned this from childhood, watching the ways his mother, grandmother and grandfather took care of each other. “Through their care, they changed me,” he says. To watch, in Morris’s world is not a passive process but an active, fire-breathing one that he describes as almost osmotic. In his childhood house, the how was maybe explained once and the why was reserved for those dedicated enough to the cause. His grandmother Carol and Morris used to watch Martha Stewart together and make dinner. She called him Martin Stewart. Home was a classroom and he learned to concentrate on your gaze remembering to look close at the things the eyes tend to skip in their haste—the maintenance, the plumbing, the bones, mom.

“A lot of people overlook mom because she’s there every day. She’s there in every way. We don’t glorify how much she sacrifices. We are just annoying little pests and she’s just there, typically in a good enough mood.”

Bowls of cereal scraped with spoons for last bites. Kids making a general mess. Grandfather relaxed with his paper. Mornings at Nate and Betty’s table unfold like a ballet with music, separate acts and interludes, the gestural shorthand of emotion.

“You sat there, and she got your ass together. Don’t be playing on her table. She watched her TV and the paper and would make herself a more adult breakfast. If you wanted it, you could have some, but I always wanted cereal. Me, my cousins, my brother, we would do that. That’s when we had our society moment. I think of the studio as a society.” There is less cereal now but the simple fixings of good manners, empathy and care paired with self-possession inform Morris’s methodologies for working. The foundlings the predator carries ome get what they need according to their ailments but always with inflexible love and devotion. “I remember the day when I realized that cleanliness was an affirmation for living well,” Morris says. “I preach cleanliness to you because I want to affirm how to live well, how you can have a good day, how you can smell the breeze, open your window, clean your floor so that you can see the shifting light throughout your day so that you can feel the energy of whatever God presence is that exists. And we can transfer that to so many parts of our lives. The actual process of cleaning your body, cleaning your home, was my first understanding of spirituality.”

The Parishioner

“I always felt pride in my family at church. At his family church, I was like, ‘This is actually holding everything—my whole family structure is here.’ A lot of young Black people, if they experienced church, know church was not only about God. Church was about Black culture. It was about living. It was a part of how you lived,” Morris says.

Church’s spectacle, especially the Baptist ones in which Morris grew up, the attention to the details of the day and the essential belief that physical objects carry emotional weight, all infiltrate the artist from a top level. I think about the work of Thomas Langain Schmidt (his soup can angel altar pieces and aluminum foil chalices). Morris is less literal in his nods to religion but they are there in the pageantry of his compositions and his love of baroque textures, and in the reliquaries. “Sometimes I might write a very personal message in the piece, and then paint over it. Then add so many things that you never knew were there. I send them out into the world at times as charged objects.”

When describing the charge itself Morris chooses the word spirit, which is as nebulous and infinity-reaching as an overmind, yet it is never spoken about in the abstract. The spirit lives in the bounds of physical reality, objects, structures, roofs—not because it has to but maybe God wants to be close to us too. “I am interested in connecting to transcendence,” Morris says, pausing. “I’ve experienced a lot of death in my life and, at first, I thought that mourning was a burden, but I think I am made to be close to mourning because I can share what I’ve learned about that transition of energy. That spirit would allow me to get through some of the hardest times of growing up. I found it in the transitional objects around me, the doorway or the window [of my house]. These things would help me find hope. I’m always trying to allude to this bigger thing.”

The Big Brother

“It wasn’t an emotional opening night,” Morris’s mother, Angela, says of attending one of her son’s exhibitions. “But then another night when I got off of work, I rolled by the Baltimore Museum of Art, and I just pulled over and started crying. I was like, ‘My son has his work in the museum.’ I just was crying, and crying, and crying. Tears of joy. Devin, being an artist, has opened the door for the kids, and the family, to see that there are other avenues. You don’t have to do the traditional things that your parents are doing. You can do something else and be successful. It was important to me, for the kids and the family to see that somebody in their family has work in the Baltimore Museum of Art. I tell strangers on the street that my son is a successful artist with work at the Baltimore Museum of Art.”

The Pioneer

Morris plans to spend the summer in Baltimore as the pilot resident for Derrick Adams’s new art space, The Last Resort. He doesn’t need a home yet but when he does all he wants in it is a globe and a dictionary. At The Last Resort, he conceded to pencils. He’s been making more with them lately because they are easy to pack—and so primary in their actions. “Dimension has always been present [in my work], but I also wouldn’t mind a graphicness so that it feels like things come off the canvas a bit. I’ve been playing a lot with shading and shadow,” Morris says.

The Artist

There is this Louise Bourgeois sculpture of two hands touching, their enveloped forms resemble an informal yin and yang. Someone asked Bourgeois what it meant. She said she couldn’t answer the question. The gesture spoke for itself. This is the kind of work Morris wants to make: “a gesture that is so strong that I would never have to explain it.” I tell him about Heidi Bucher’s “Skins” series, how she would pour latex all over her childhood home to try to make impressions of it. I think his work is like that, especially the performances. Something about home and trying to channel that energy through lavishing the memory with abundance. Something about trafficking exclusively in the emotionally loaded. “I start every work wanting to cry a bit,” he says. “I thought my crying and even my honoring others was due to mourning, but it is not. It’s just that I am interested in sharing and pulling emotion, navigating it as textural material.”