There is something so wholesome and grand about a biennial that it doesn’t feel sufficient to write a sole critique to describe it. To measure up to all the work that went into it by curators, artists and handlers, the critic must come to some larger conclusion, whether praising or scrutinizing the final result. The writer is given a couple of days. The biennial team is given two years. Neither timeline seems sufficient to produce something that lives up to the expectation of spectacle and premise and this thought makes it hard to want to do much more than admire the handiwork of what was possible and buy the catalog as a time capsule.

Walking up to Whitney Museum of American Art’s 2022 Biennial I felt tight, like buying a ticket to a horror film I might not be able to sit through. Never have the contents of any biennial ever revolted or terrorized me—maybe apart from Jordan Wolfson’s Real Violence—but the aftermath has, when the show gets teethed on by press and art viewers who try to get their mouths around a survey that is designed to be too large to swallow. Inevitably, a biennial’s insides can never be bombastic or radical enough to hold all the discourse that will be placed on top, let alone the hurt feelings of those not included and the chips of more generalized haters. This year’s edition, “Quiet as It’s Kept,” curated by Adrienne Edwards and David Breslin was so economical, my objections turn to the setting itself.

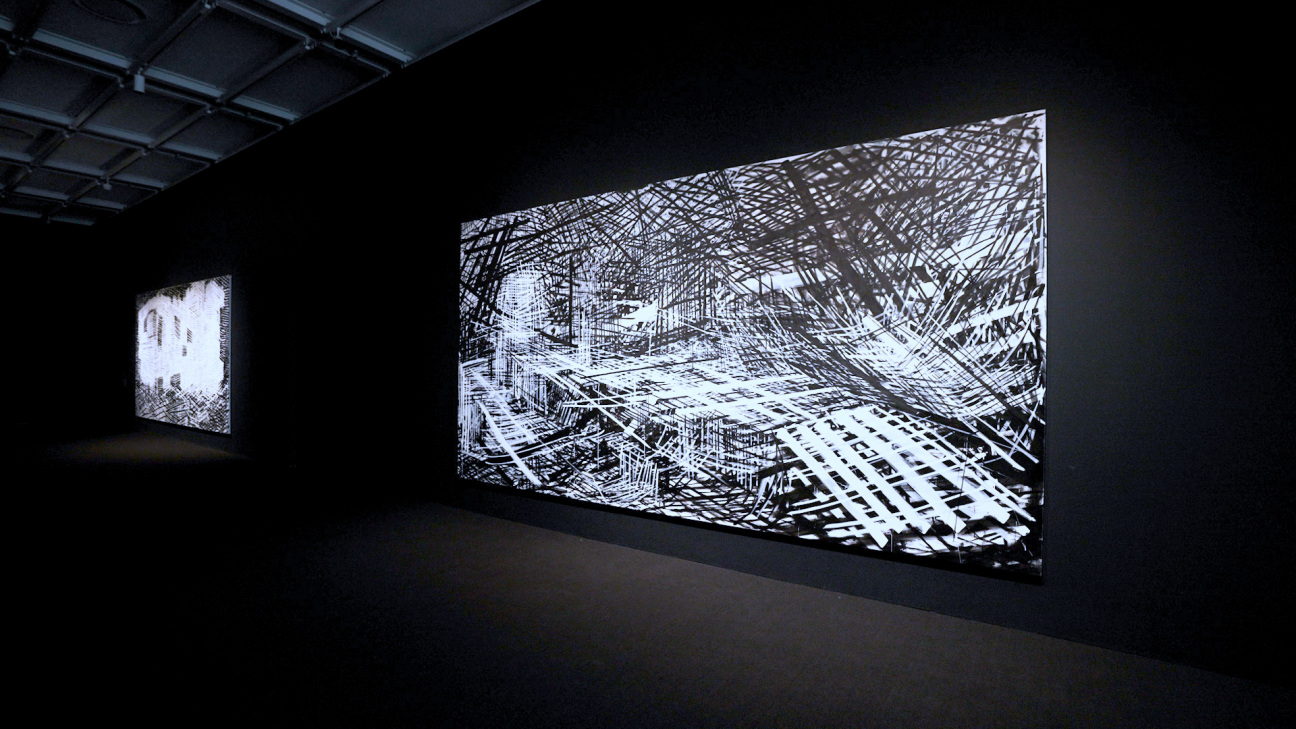

My initial thoughts are always about what I would've wanted as a participating artist and are, therefore, often about real estate: the dark black box theater of the sixth floor verses the open plan lightness of the fifth or the infamous stairwell, the third floor in between or the wide tongue of the lobby. On any day, I would choose cubby intimacy and labyrinths over the hygiene of daylight. The black walls did little favors for the paintings and sculptures put up there except Denyse Thomasos’s gigantic cross-hatched landscapes, which draw a silent ‘wow’ when the elevator doors shush open. I like the way you walked between this diptych about confinement to see Thomas Edison’s bottled last breath on a pedestal.

Even if you can’t hear it, the language of confinement is pushed beyond itself in these rooms and the juxtaposition set me up to be excited about the rest of the floor. I sincerely enjoyed fumbling for more secrets in the velvet light; I wanted to linger to read all those glowy Jonathan Berger texts and wait for the green light to indicate that Alfredo Jaar’s film had started.

Meanwhile, the fifth floor inspired the opposite effect: I was confronted with everything all at once. It forced my eye towards the things I knew: Sable Elyse Smith’s now signature prison table, Harold Ancart’s oil stick terrains, Alex Da Corte’s slickened Pee Wee playhouse, Woody de Othello’s oversized ceramic props, Rose Salane’s poetic lists. I even mistook some artists for others in my quest to orient. I saw Andy Robert’s zombies and though Ed Atkins. Art fairs often generate similar snafus as the ubiquity of content blinds me to the details. Out of survival, my brain is subconsciously simplifying what I am trying to keep complex.

I jumped into Rodney McMillan’s stairwell for relief where his hanging painted column disrupts architect Renzo Piano’s idea about institutional transparency. You can’t see the other people looking at the same thing until they turn the corner. It is a communal viewing experience where everyone is given the privacy to look alone—a luxury I appreciate more at museums than other places.

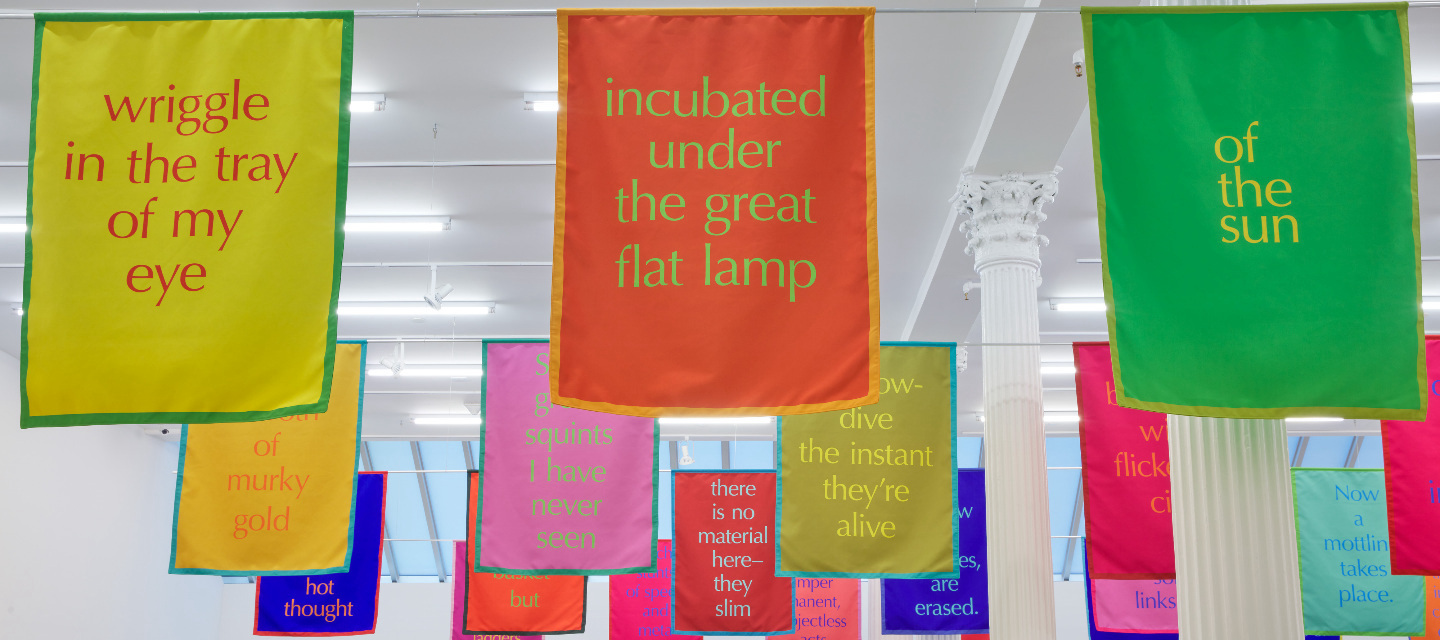

Respite was also found in the Cassandra Press reading room replete with Barcelona chairs in fetish red and all the tomes I then immediately regretted not already having at home. Texts made their way into this biennial in a natural way without ever leaving the physical world behind, from the title—a reference to Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye—to Tony Cokes’s digital screens and Renee Green’s banners, read aloud by rubbernecking viewers in the lobby.

I left the show with a sense of pride for artist friends who had made it to this professional height, and a question about biennials and how they could be reformatted to meet their grand expectations. What I admired of “Quiet as It’s Kept” were the spaces where artists were truly allowed to take over the architecture and make their own context. Their individual takes felt more important than a thematic whole. Perhaps that is what we should come to expect.