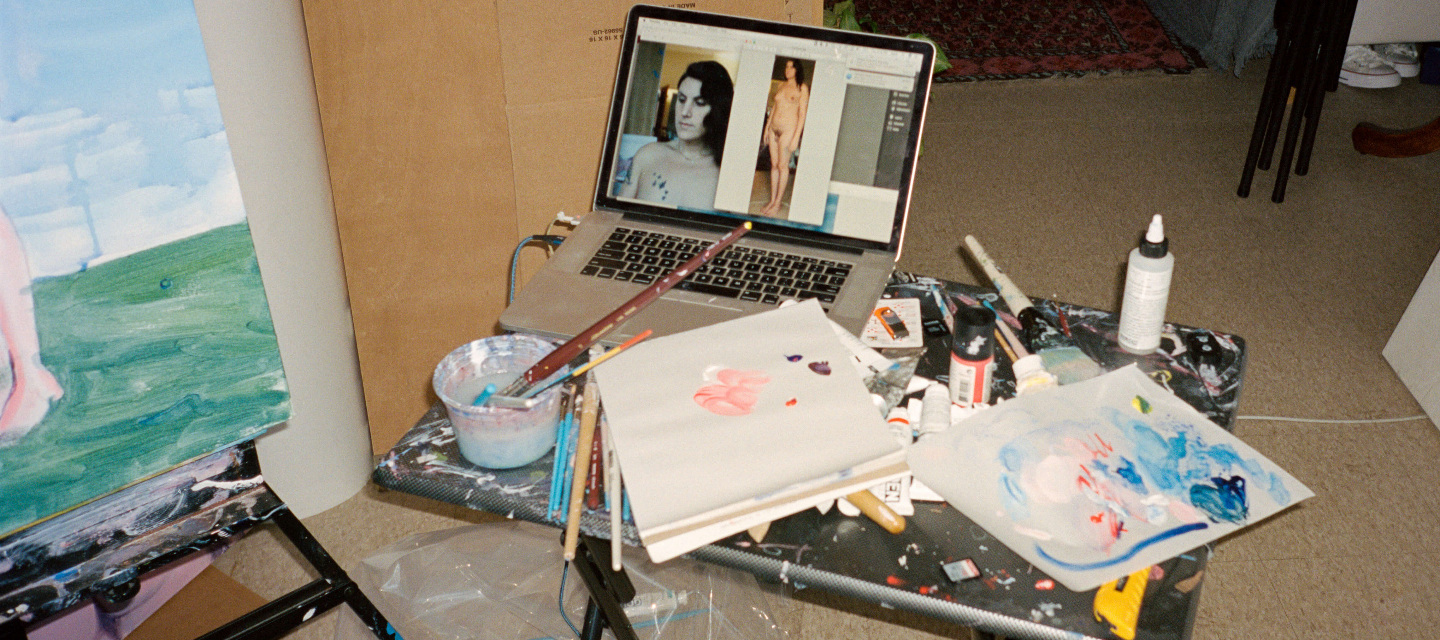

The figure is Glynn, and she is painting when I arrive. Her apartment is warm and clean. There is goopy, colorful art on her walls, but she says it’s all her partner’s. “It used to be bare here when I lived alone,” she tells me. “I need the blankness to work. But it’s nice to have stuff around.” Next to her easel is her laptop, an iPhone tripod and a bottle of water. Untitled is in some ways a signature painting of Glynn’s: a self-portrait of a naked figure in an ethereal, natural setting. In a bigger version, like Self-Portrait with One Foot Forward and One Hand Reaching Out (2020) the figure steps into a colorful, idyll nature scene with tufted, violet clouds and green-yellow fall foliage. She is barefoot, a giant goddess—the trees come up to her ankles. She neither springs forward nor sinks into the foreground, floating on the surface. She beckons you into her world. These natural scenes often have ruptures, if you look closely. The little circle at the bottom left of Sunset (2021) is like a little glitch in her matrix. While these landscapes may appear to be placeless, like stock images, they are usually based on a picture of a place she has been. “I was feeling sad in Vermont,” Glynn tells me of the circumstances that led to the picture in the background of Self-Portrait with One Foot. Life, heartbreak, betrayal and friendship seem to press themselves just beyond the frame of her Eden, lying in wait like shared secrets.

Glynn learned to paint at her father’s set construction company in Miami, Florida. Her brothers would get sent to do construction and she would get sent with “the one other woman and the gays” to the scenic department, where she painted sets for plays, theaters and amusement parks. Eventually she joined an arts-focused Miami public school, primarily to continue art, but also because she learned she wouldn’t have to take gym, and the thought of being in a boy’s locker room terrified her. During her undergrad studies at School of the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University, she stopped painting, before picking it back up in grad school at Columbia. Even now, Glynn feels a primordial draw to painting describing it as a “survival mechanism.” “I wasn’t planning on going to grad school. I also wasn’t planning on transitioning. I thought about putting grad school on hold because I wanted to hide. But then I needed to paint again.”

At yoga two weeks later, we lie next to each other in shavasana and talk about how hot the guy behind us is. We also talk about the conflicted burden of representation, the types of visibility that institutions ask of marginalized people. She wonders out loud if she can ever just be “a painter,” or if she’ll always have to be a “trans painter.” Self-portraits have been a way for her to take charge of her own image. But sometimes she can be interested in more fundamental things—like time and space, she tells me, or more formal concerns: “How little does it take to signal an inside and an outside?” In her recent works at Vielmetter in Los Angeles she’s testing these waters. The show consists of two paintings, Interior #1 and Interior #2 (both works 2021), which depict the front and the back of a self-portrait, displayed on two sides of a column in the center of the gallery. Here, the wall became a sort of minimalist sculpture, an extension of her interest in the binaries that construct architecture, painting, but also heterosexism.

In a spare, wistful painting like If You Were A Cup (2021), the canvas is white and the only object is a wine glass with pink and blue flowers. A soft, blue line connotes something like a table, floor, or a wall. This economy imbues her surfaces with a certain mystery. Like, who is she??? Glynn has been doing self-portraits since an early age, and they’ve become a way for her to celebrate her visibility. But these still lifes are also very intentional. The juxtaposition between still lifes and self-portraits in her oeuvre imbues each genre with the aura of the other—is the flower Glynn? Is Glynn a flower in a landscape? In this light, paintings like Before (2020)—a knife with an apple—and After (2020)—a knife and a sliced apple—take on metaphorical resonances. Are these about surgery? Are we extrapolating from her identity in a way that oversteps? It could also just be the passage of time, as expressed through painting. Ultimately it’s both. “I named my tits form and content,” she tells me, succinctly wrapping up her philosophy, “because you can’t tell the difference.”

In the next few months, she’s preparing for a big solo show at Vielmetter set to open next fall 2023. She’s not exactly sure what’s next, but she knows that she wants to work more intuitively, to not have so much of a framework all the time. After yoga, she drives me in her tiny car and we go to an opening downtown together. This fall feels like winter. “I just want to play more,” she tells me, and we step into the crowd to look for our friends.