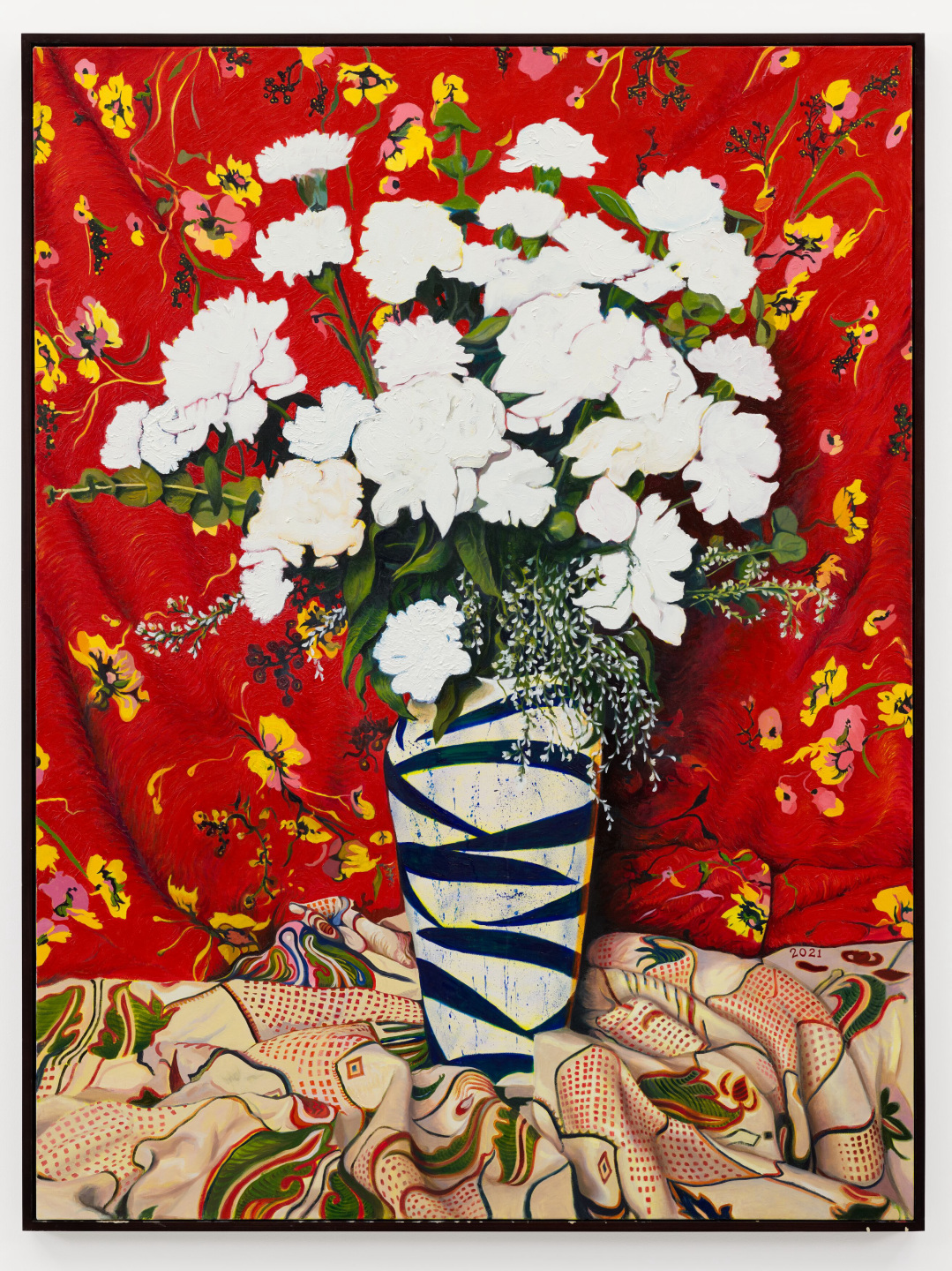

It feels strange to call Keith Tyson a still life painter but his latest Hauser and Wirth exhibition in New York elevates the most seemingly basic of content, that 16th-century Dutch mainstay—flowers—to lusty, conceptual delight. Of course, there’s also much more to Tyson than his floral explorations. Unconfined by a signature style or medium, the self-taught polymath and 2002 Turner Prize-winner’s work spans installation and sculpture, drawing on a range of influences, from science and algorithms to poetry and mythology.

“Although they’re all still lifes, each one is its own separate universe with its own separate reason for being,” says Tyson of his new paintings, made mostly in social isolation, which he describes as upending his normal practice of embarking on numerous projects simultaneously. Given the restrictive space of the shed-cum-art studio opposite the house where he was staying for the pandemic, he tackled just two paintings at a time. “My fundamental principle is that if you’re going to be honest about creativity, we’re different people at different times,” he confesses. “A lot of the art world tends to be about branding. I’m more interested in how complexity emerges from different activities.”

Consider Still Life Floating in Space, 2020, in which crude bionic limbs clench the stems of a minimal floral bouquet. “That is a painting which I conceived fully from the beginning, while others emerge from a process,” explains the artist. “I set up a whole structure with little robot arms and made a still life, which was very much like a Japanese ikebana arrangement, almost mathematically delicate.” He then photographed the simulation, before realistically representing the creation on canvas, adding: “There was almost a film production quality in terms of the production of that picture.”

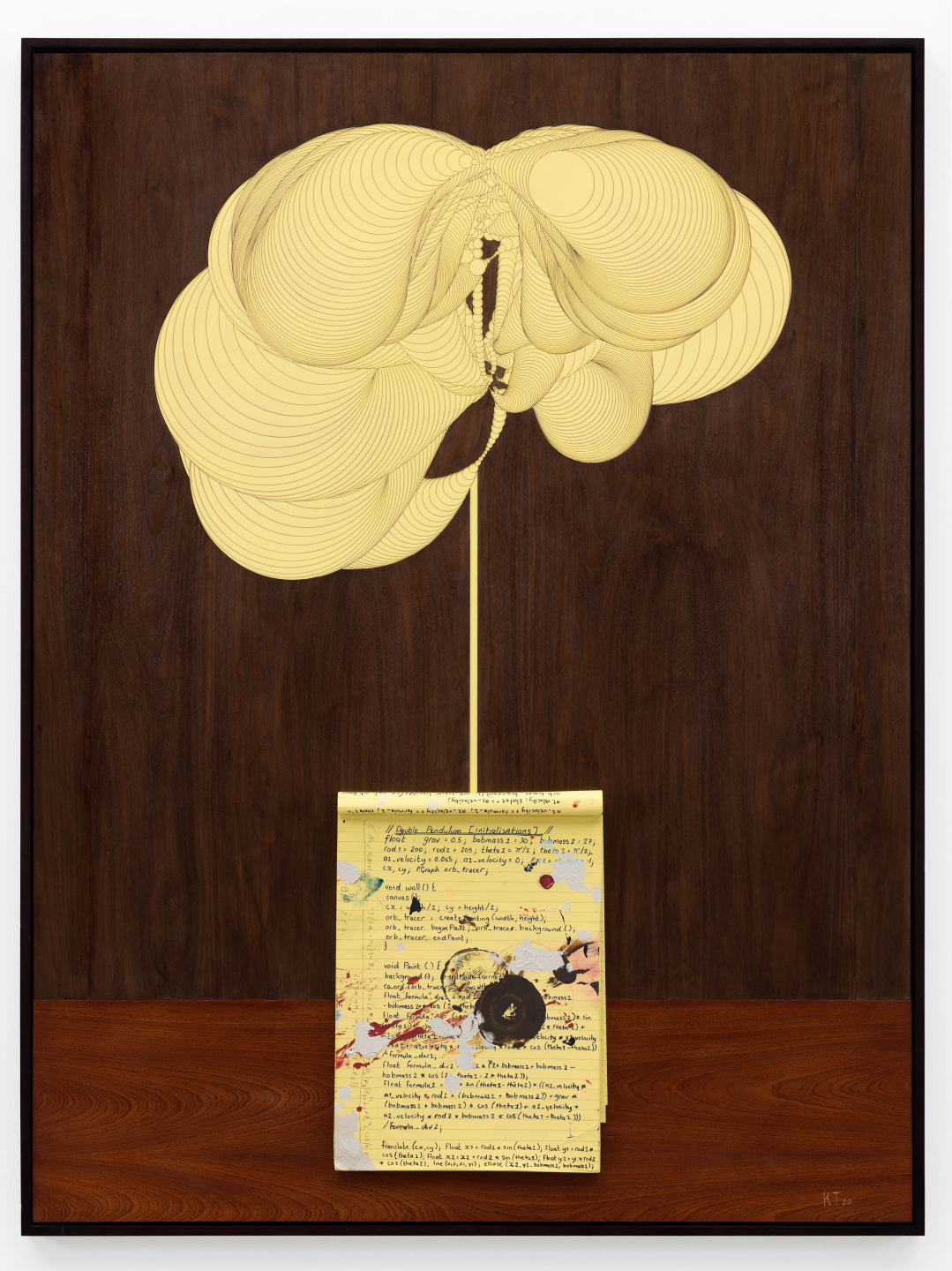

In contrast, Still Life with Double Pendulum, 2020, springs from the physics of the double pendulum (a pendulum with another attached to its end), whose swings become unpredictable once set in motion. The composition evolved as Tyson worked. “I coded a double pendulum into my computer and saw the blossoming of this shape, and so I inverted it and created this piece that looks like a still life,” he explains. “The wood grain in the background of the work has a similar gradation.” But instead of being based on chaotic mathematics, they are based on the complex weather conditions and dendrochronology of the trees from which the wooden inlays are derived.

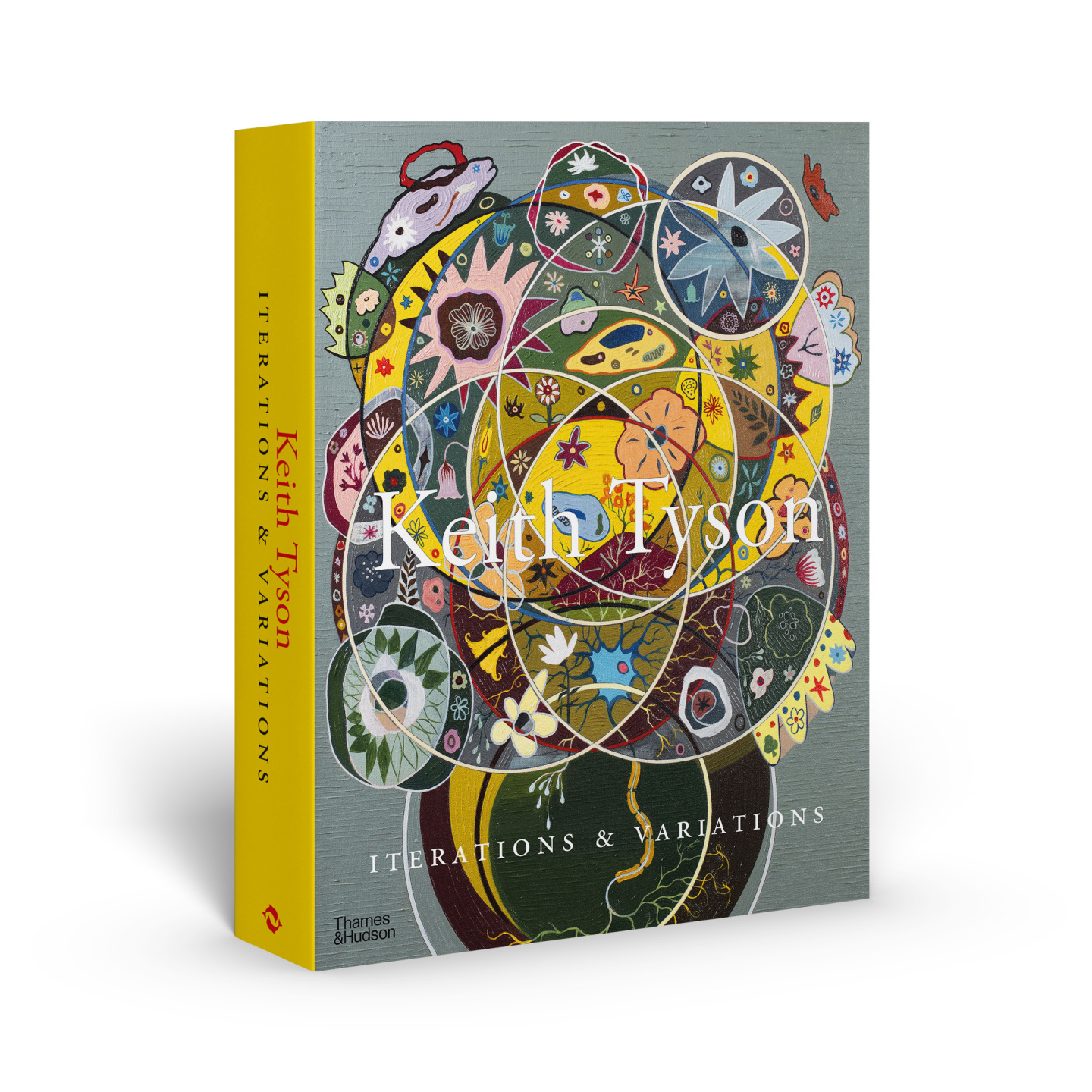

In May, Thames & Hudson will publish the artist’s first monograph Keith Tyson: Iterations & Variations, a magnificent, mammoth compilation celebrating the artist’s disparate 30-year career. The floral paintings will be well-represented. “It was a big challenge to put all of this work that’s had so many different approaches into something that makes sense,” Tyson says of the process of making a book. “I guess if I had a mid-career retrospective somewhere and they made a catalogue, then this would be it.”

in your life?

in your life?