Winfred Rembert’s complex, autobiographical paintings over 25 years tell the harrowing story of the Jim Crow South and its racial violence through the traumatic memories of an artist who survived near-lynching, captivity and Georgia’s barbaric chain gangs to create a joyous family with his wife, Patsy, in New Haven, Connecticut. “Winfred Rembert: 1945-2021,” which opens today at Fort Gansevoort’s Meatpacking location in New York and is on view through December 18, is a raw and urgent posthumous exhibition of 23 figurative, tooled leather works by the still relatively unknown artist. His images are a record of the racism that imbues the nation’s fabric, one that every American should see. But the compositions are also a portrait of profound human dignity, a celebration of Blackness and a display of the technical mastery of a prolific painter whose artistic legacy—alongside standard bearers like Kerry James Marshall, Jacob Lawrence and Faith Ringgold—merits a major museum retrospective, with over two hundred works to draw upon.

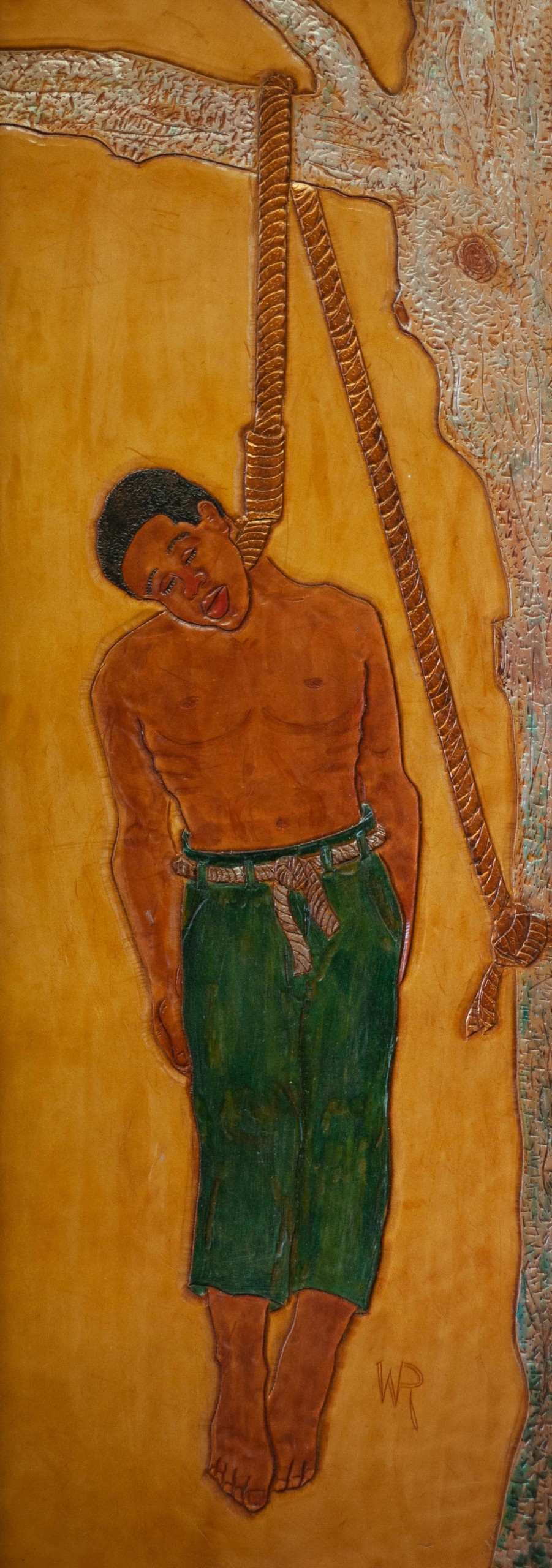

Born into poverty in the rural midcentury South and given away as an infant to his aunt, Rembert grew up toiling in cotton fields with minimal formal education. In 1965, at a Civil Rights protest in Americus, Georgia, police arrested Rembert, who, after over a year in jail without being charged, escaped his cell by clogging a toilet with a roll of paper and causing a flood. He was caught, stripped of his clothing, hung from a tree by his ankles and knifed in the groin by a mob of white men. Rembert survived only to be put back in prison and on a chain gang until his release in 1974. While incarcerated, he learned to tool leather from “T.J. the Tooler,” who was allowed to craft items like billfolds and belts. But it wasn’t until the age of 51—living in New Haven, with the encouragement of his wife Patsy—that Rembert began documenting his life and mining his memories through art, carving vivid, emotional scenes on hide.

The New York exhibition coincides with the recent publication of Winfred Rembert’s autobiography, as told to his co-author Erin I. Kelly, Chasing Me To My Grave: An Artist’s Memoir Of The Jim Crow South, by Bloomsbury, and the gallery provides narrative excerpts alongside each artwork to contextualize them. Visitors also have the chance to hear audio recordings of the text from contemporary artists such as Dread Scott, Hank Willis Thomas and Tschabalala Self. “It almost seems like Winfred has a photographic memory,” says Adam Shopkorn, who cofounded Fort Gansevoort with his wife Carolyn Tate Angel in 2015. “It’s a miracle that he lived through all of the events of this exhibition. When you get to the top floor, the wall text from his memoir reads: ‘And when I die, I didn’t die by the rope. I just died from being an old man. I lived my life out.’”

It was six years ago at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art that Shopkorn encountered the painting The Dirty Spoon Cafe (2002)—a saturated, intricate childhood memory of a juke joint in Rembert’s hometown. “It stopped me in my tracks,” he recalls. “That’s where it all started, seeing that painting in the flesh.” Eventually, Shopkorn approached the Remberts to curate a historical exhibition, but one with the courage to display traumatic, terrifying pictures—the nightmares, as he describes it—that haunted Rembert. “That’s not to say that I don’t think the juke joints and the billiard halls and the cabaret scenes are fantastic,” Shopkorn adds. “But the more horrific things that happened to him in his life really need to be brought to the forefront, no matter how hard it is to process.”

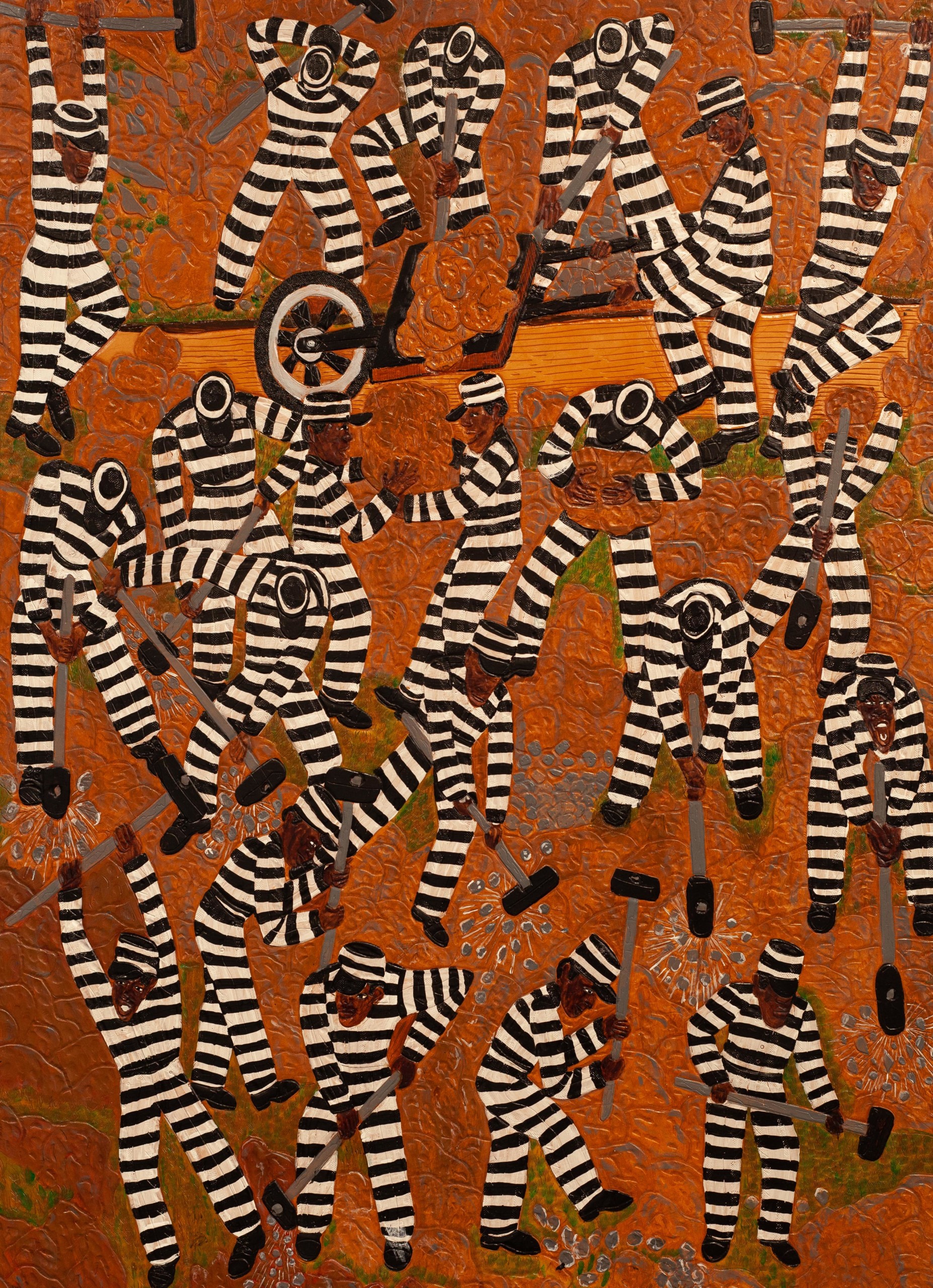

Two paintings in the gallery show stand out most vividly: All Me (2002) depicts a semi-abstract mass of figures in prison stripes that blanket the surface, an allegory for the multiple personas needed to survive the brutalities of prison. In Rembert’s words, “[E]ach person in the picture has a role to play. I didn’t want to play any of the parts, but I had to be somebody. I couldn't walk around and be nobody, so I became all of them. It’s like I was more than one person inside myself. In fact, I think if I hadn’t decided to play the All Me role on the chain gang, I wouldn’t have made it. Taking that stance—All Me—saved me.” Yet the work has a ghastly universality that echoes modern forms of dehumanization, recalling the mounds of eyeglasses and shoes from Auschwitz, and the tangled piles of bodies in mass graves. The other is the exhibition's final painting, Almost Me (1997), which serves as homily and epilogue: a single limp body hanging from a noose, what might have been—and what has been throughout history—a fate narrowly escaped.

The artist’s medium, too, serves as metaphor. “My pictures are carved and painted on leather, using skills I learned in prison,” Rembert writes in his memoir. “Leather takes a beating, and whatever you do with it, it will hold its shape. You can carve it up and it will hold your picture.” Several days before the show’s opening, I viewed the exhibition with Patsy, who described her husband’s process of sketching his scenes first; then, with surgical precision, he would select from a hundred instruments in his toolkit and begin his meticulous draftsmanship, chiseling his story onto cowhide. “It’s no surprise to me what I’m reading or seeing now,” she says of the current artworks on display and his writings. “I’m just so glad and proud that he got the chance to put down the things that he did, to talk about his life and all that went on in it. He didn’t hold back on anything.”

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.