Early in the pandemic, Rashid Johnson fled New York City with his wife, Sheree and their son Julius, and settled into their weekend home in Bridgehampton. The six-acre, wooded property was not a bad place to be, but still, events in the world outside left Johnson wracked with anxiety.

In the studio, he returned to a motif that had first entered his work in 2014, a time when America was turning towards right-wing populism and videos of police violence against Black people were being shared with increased frequency on social media. Johnson was grappling with parenthood, his newfound sobriety and the demands of his career. The motif that emerged was a cartoonish face with wild staring eyes and grimacing jaw that Johnson repeated, contained within rectangular cells, over and over across his canvases.

Made during the early months of the pandemic, his series of “Anxious Red Paintings” debuted at Hauser & Wirth in London in October 2020. Fast-forward almost a year, and the world seems a very different place. “Black and Blue,” Johnson’s new exhibition at David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles, is his latest reckoning with himself, the world, and his place within it.

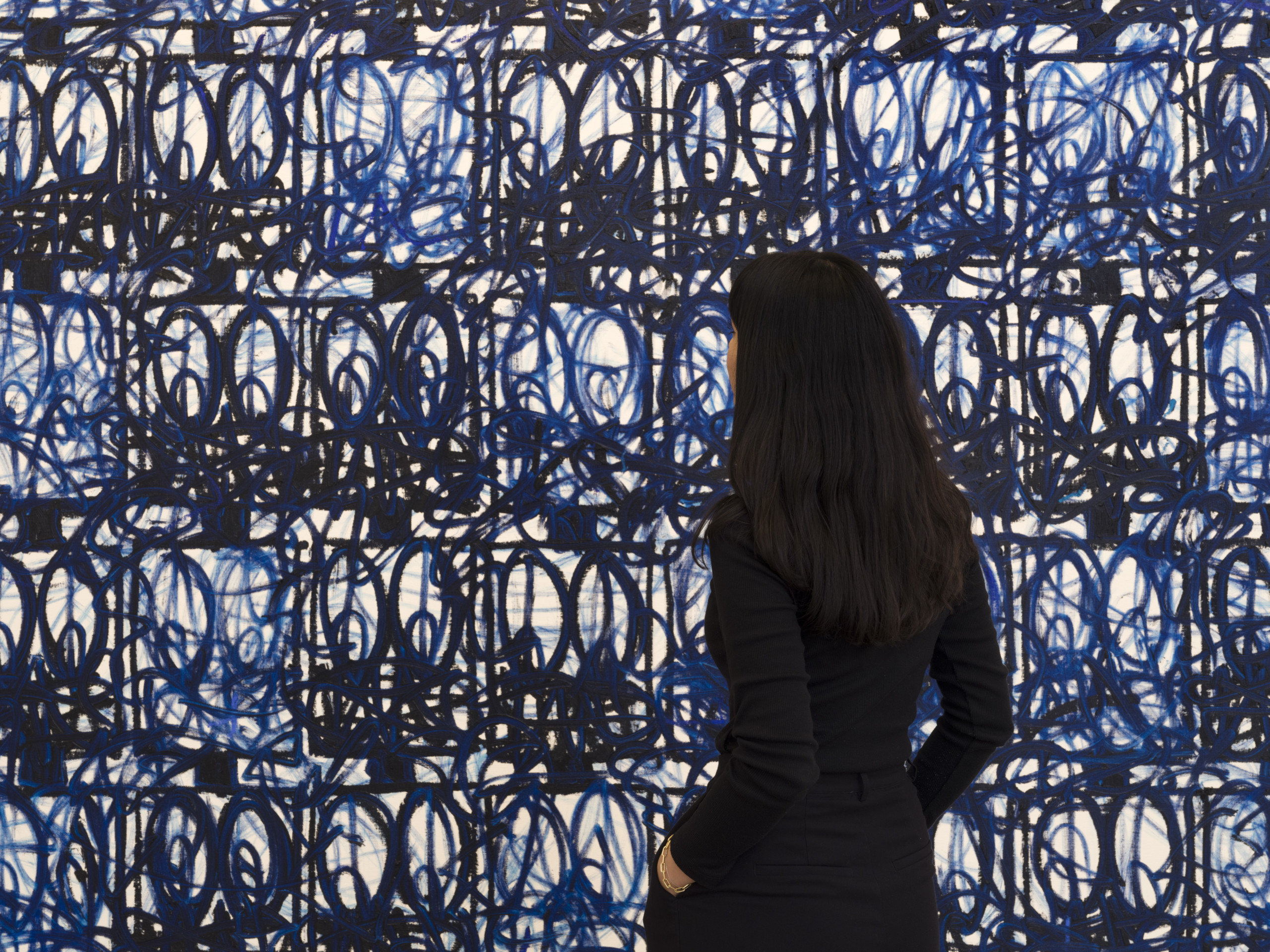

The tone is set by six large “Bruise Paintings”—all iterations of the “Anxious Man” motif, here rendered in shades of black and blue. The bruise, Johnson tells me as we walk through the gallery, represents “a liminal space between the blunt force trauma and a potential opportunity for healing.” Although, he adds circumspectly, “whether that's actually going to be what we get out of this or not, in all honesty, I'm not sure.”

While painting, Johnson listens to audiobooks and music. In the lead up to this show, he returned to a record by Louis Armstrong: “My only sin is in my skin / What did I do to be so black and blue?” Casts of vinyl recordings of Armstrong’s rendition of Fats Waller’s “Black and Blue” are inserted, like circular blades, into large bronze planters brimming with succulents and cacti, their churning surfaces expressively worked by the artist in clay.

Oyster shells, another recurring motif in Johnson’s work, appear on the planters too. In her 1928 essay “How It Feels to Be Colored Me,” novelist Zora Neale Hurston states she is “not tragically colored.” Hurston writes: “No, I do not weep at the world—I am too busy sharpening my oyster knife.”

While not all of Hurston’s polarizing text reflects his own relation to race, Johnson particularly relishes that line. In a short 35mm film, also titled Black and Blue (2021), we see Johnson in his comfortable home, going about his day: waking, brushing his teeth, reading while his son does his homework and, in one memorable scene, shucking oysters at his dining table.

“The interesting thing,” Johnson says with a smile, “is you don't sharpen an oyster knife! It’s meant to be a blunt instrument. So what is she doing? Is she making a weapon?” He enjoys the ideological ambiguity. “That’s where the power is.”

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.