Trying to get a handle on the unwieldy Cuttica family at times feels like I’m trespassing. Maybe it’s because they live together on a 40-acre former duck farm turned nature-preserve-cum-artist’s-compound in Flanders, New York, along with guests and tenants like driftwood horses, massive acrylic portraits and two Boston terriers.

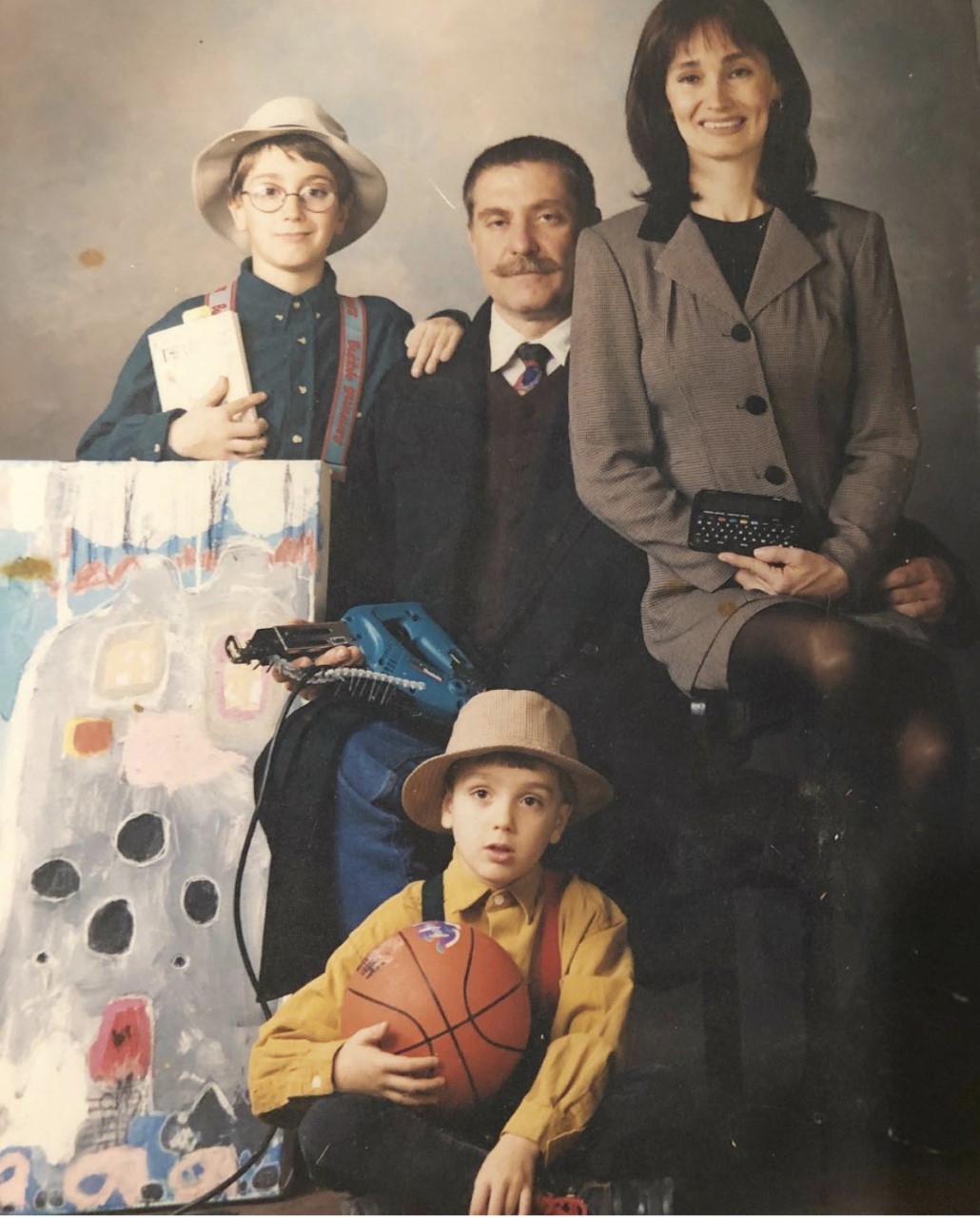

The family’s story, however, does not start on a sizable retreat down the street from the Hamptons, but rather in Buenos Aires. Eugenio Aldo Cuttica had a burgeoning painting career when he crossed paths with Ruth Elizabeth Keudell, a businesswoman, in 1982. The couple was married two years later and together ran a successful clothing company in Argentina, while Eugenio continued to paint.

To escape political turmoil the family, now including sons Lautaro and Franco, decided to move to the United States in 1996. They took a leap of faith and sold all of their belongings to lighten the load. One of the few traces of their former life: a wooden sign that reads, “Trust your crazy ideas,” which now hangs on the front door of their mostly glass home, which the family refers to as the “tree house.” The Cutticas settled in New York City, a nexus of opportunity, art and world culture. Of course, artists move to New York to become known, but Eugenio was already a household name in Argentina.

Even after Eugenio left, it was important for him to stay connected to his Argentine roots, so he maintains a studio in Buenos Aires. While travelling back and forth between his studios in Argentina and New York, he has compiled quite the resume, including “Ataraxia,” a 2018 exhibition at MAR Museo de Arte Contemporáneo in Mar del Plata, and a retrospective, “La mirada interior” (The Inner Look), at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires, in 2015.

Only after coming this far, did Eugenio realize a higher calling. To him, the logical conclusion of a lifetime in and of art was to help others actualize their own artistic dreams. Together with his family, he conceived the idea of an artist residency, where artists would create and live at Campo Cuttica under the guidance of Eugenio. While the residency program is still in the developmental stages, Eugenio of course has some experience, already having raised two creative sons who grew up putting their little feet in paint buckets around their father’s studio.

Franco, now 30, gives me a private virtual tour of Campo Cuttica. Opening the doors to the largest studio on the property reveals a 30,000-square-foot stable full of Franco’s life-sized horse sculptures. Each caballo is pieced together from meticulously chosen driftwood he finds on beaches around the world.

Franco purposefully leaves gaps within each horse’s form, creating the illusion that they naturally washed up on shore this way. While some horses end up in collections as stand-alone sculptures, to Franco, they are actually only half-completed. His signature performance is arranging these horses on a shoreline and setting them aflame. He likewise sources baby grand pianos from listings in surrounding neighborhoods and gives them the same treatment, a performance-art reminder of life’s impermanence. I can tell that Franco’s favorite tool in his belt is fire; he refers to his blowtorch as his “brush,” which he uses to burn portraits onto large canvases.

This year Franco’s main project was the construction of a tiny house on the property using materials sourced from local listings. One seller even agreed to give up hardwood flooring in exchange for a portrait of his cat. He listed the tiny house, built with his own two hands, on home-sharing sites, and it became such a popular rural escape that Franco now finds himself a proud part-time property manager.

Across the campo, we run into Lautaro, 33, at work in his studio. Although now a painter, Lautaro studied architecture at Cooper Union, a training reflected in the sense of space and perspective in his work. Lautaro’s latest collection of paintings is more energetic and expressionistic, as Franco describes it. He uses a technique involving layering and mixing heavy brushstrokes of oils and acrylics to achieve a vibrance that neither medium on its own could deliver. As I should have expected, Lautaro’s wife, Isadora Capraro, is yet another artist in this family of artists. With meditative mindsets and vibrant colors as inspiration, Isadora, working in acrylic, depicts people in yoga poses along with the animals they mirror.

Who you won’t see roaming the studios happens to be the engine powering the Cuttica family’s operations. Ruth is the impetus behind this family’s business endeavors and their lives outside the studio. Her upbringing instilled in her productivity and pragmatism, both things she brings to the Cuttica family table. When the family moved to the States, she ran three Tasti D-Lite frozen-yogurt locations in lower Manhattan, which became the family’s financial engine. From selling art to finding new clients and organizing gallery openings, Ruth makes it possible for the Cuttica family to live a life of art.

Despite the family’s resilience, even they felt the effects of the pandemic. Franco describes artists as “already being in quarantine” by nature, so lockdown orders felt like “double quarantine.” The job of an artist is two-fold, Franco explains: “That’s why quarantine is hard for artists... The whole other aspect to our career is getting out, meeting people and making connections.” Although the individual members keep to their own projects, the family had been all-hands-on-deck before the pandemic hit, helping to actualize their dream of creating the residency program on the campo. They plan on jump- starting this endeavor as soon as they possibly can.

Concluding the tour, we come to the main studio, housing some of Eugenio’s most famous works and his collection of classic cars. The recurring character in Eugenio’s multilayered acrylic paintings is a young girl named Luna. She perches herself on high chairs while looking out onto expansive pastures, changing leaves and grandiose seascapes. Luna embodies Eugenio’s philosophy, perhaps something not told often enough, that “everyone is born an artist.”