In 1975, towards the end of the nine years that he spent living in Europe, Paul Thek went to Paris to stage an exhibition at Galerie Alexandre Iolas. Although the show was postponed, Thek stuck around the French capital and produced a series of 28 etchings, all of which are on view now in an online show titled “I Am, Am I?” courtesy of Alexander and Bonin. These are the only etchings Thek is known to have made after his student years at Cooper Union. The copper plates were discovered in a box of books in his storage unit in 1989, a year after his death, where they were hidden between the pages of Emile Durkheim’s Suicide: A Study in Sociology and Nino lo Bello’s The Vatican Empire.

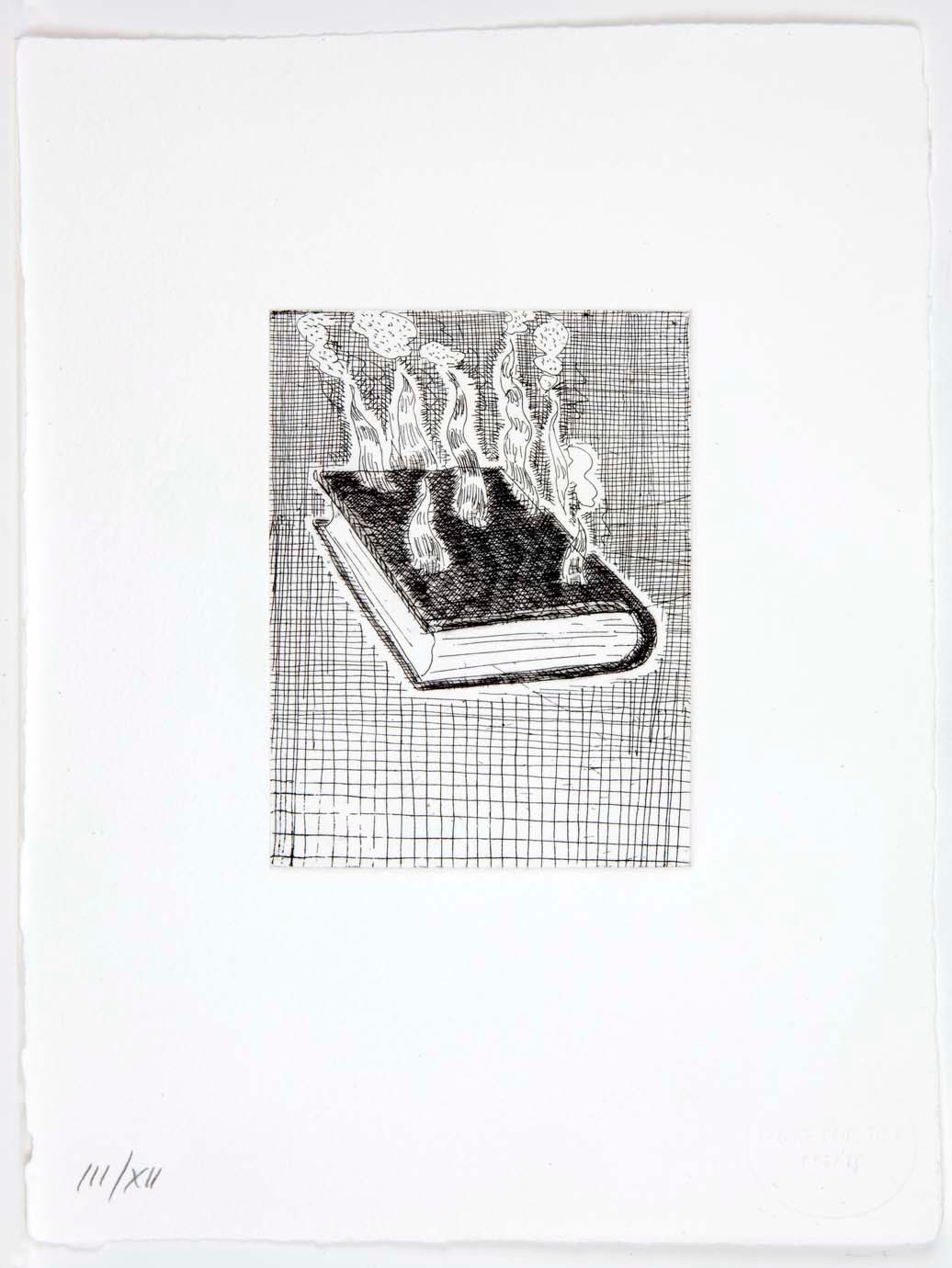

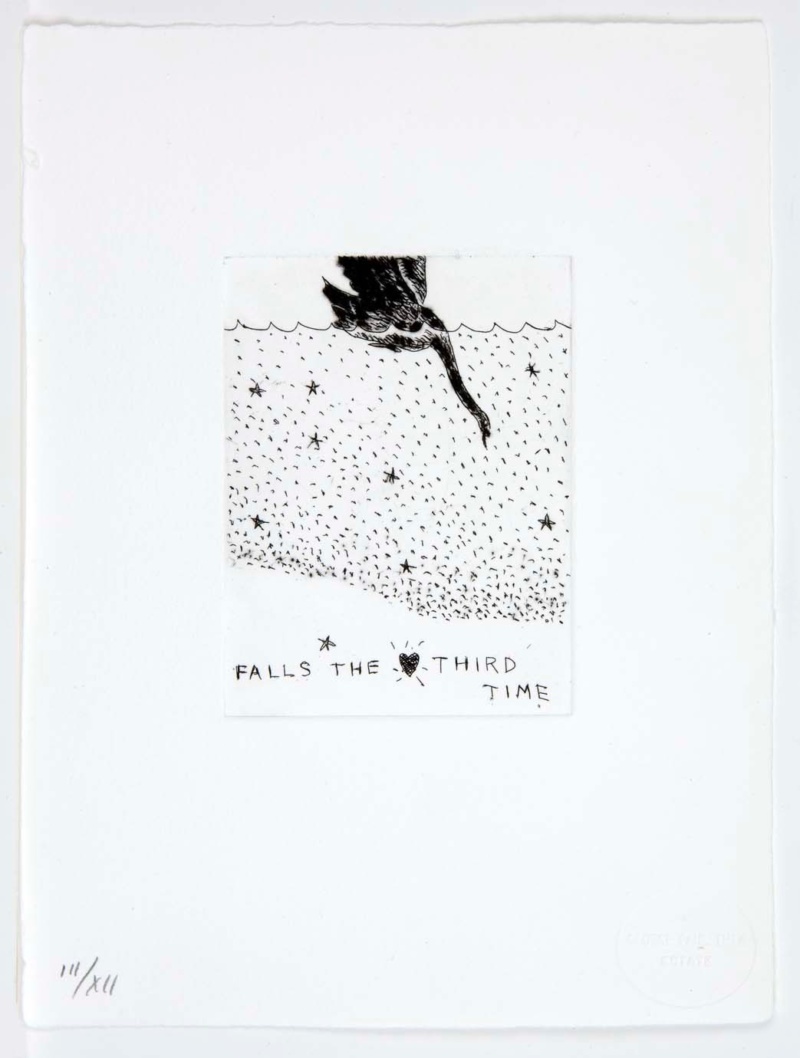

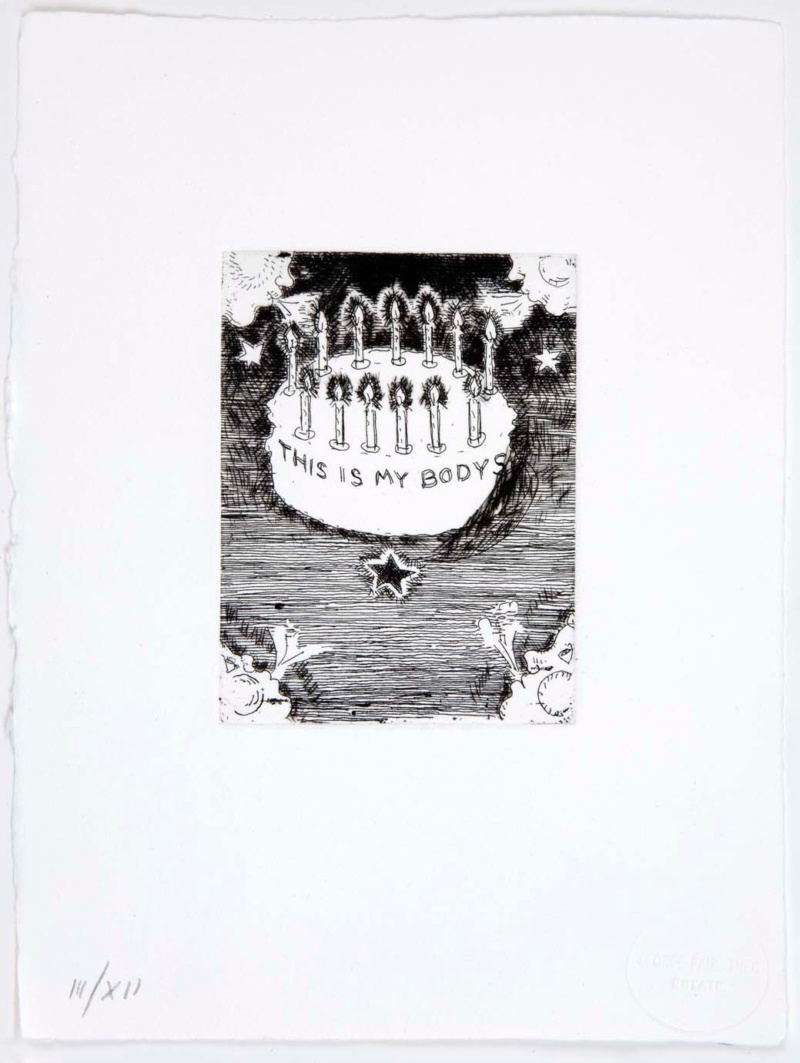

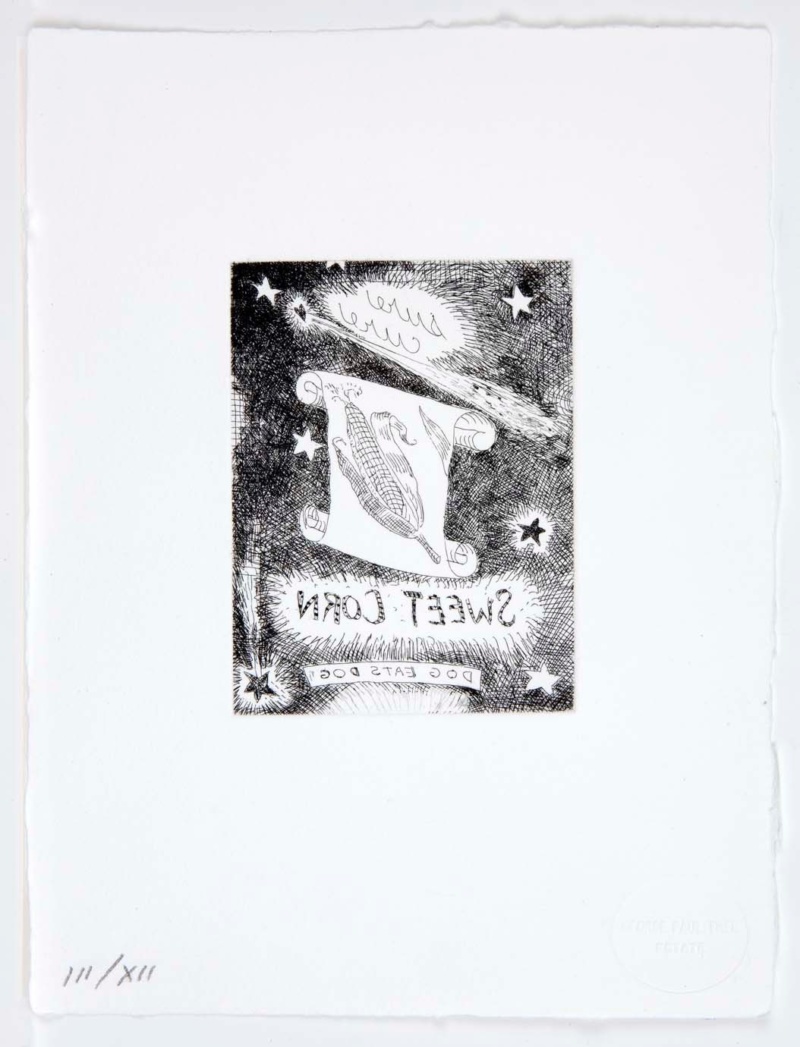

Though Thek is most widely celebrated as a sculptor, it’s his drawings, paintings and notebooks that I return to again and again. The immediacy of these mediums made them ripe territory for someone with a mind that moved as fast as his. These etchings now join the other flat works as a place where he managed to capture and hold the contradictions that make life what it is. A devout Catholic who struggled to bridge his faith with his homosexuality, a man in love with life and hounded by death, Thek brought all of these messy paradoxes into the work. A number of the etchings include biblical references: Untitled (Falls the Third Time) alludes to the third station of the cross and shows a swan dipping its head below the surface of water. It recalls his Diver paintings, from 1969–70, which depict a nude man diving into a body of water. The water in these works is often read as symbolic of the afterlife; that the swan and diver are both partially submerged suggest a transitory period between life and death. In Untitled (This is My Bodys), a birthday cake floats in space with four cherubic faces blowing out its candles, an allusion, I assume, to the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation. Who wouldn’t rather be a birthday cake than a stale wafer?

As Thek aged and as the AIDS epidemic—which would ultimately claim him as well—wove death more firmly into the fabric of his life, his work became more and more childlike. In 1988 this culminated in the final show of his lifetime, for which he made crudely rendered paintings on recycled newspaper, hung at the eye-level of a toddler with kindergarten chairs placed before each one. A number of the etchings on view in “I Am, Am I?” presage Thek’s subsequent drift into these childlike, faux-naïve tendencies. This instinct, which arrived with death in the rearview mirror, makes me wonder if Thek didn’t have yet another parable from the gospels in mind: Christ telling his disciples, “unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.”

in your life?

in your life?