Often commenting on conditions of displacement, the work of Tehran, Iran-born multimedia artist Hadi Falapishi questions the ability of representation to convey truths, revealing the gaps between public perception and personal experience. Most interestingly, his photographs are made without the use of a camera, but in his darkroom where he employs a flashlight and exposes objects, ideas, concepts and, perhaps, even dreams to photosensitive paper. The result? Beauteous creations that, through their colorful visual storytelling, inspire contemplation and serious yet humorous (at times) consideration of the universe that surrounds and engulfs us.

I first became aware of the artist’s work last summer in the group show “A Love Letter to a Nightmare” at Petzel Gallery in New York. I was intrigued. Since then, he has gained quite a bit of art world attention through shows at Efremidis in Berlin and Andrew Kreps in New York. Soon, Falapishi will open a new exhibition at London’s Rodeo Gallery and is currently working on a limited-edition project with New York’s SculptureCenter. His book Truth Has Four Legs will be published later this spring by Zolo Press. On a recent chilly afternoon, I traveled to Falapishi’s Red Hook, Brooklyn studio for an intimate, socially distanced sit-down with the artist and the writer Sascha Behrendt.

Ricky Lee: What’s the process and inspiration when you make these images?

Hadi Falapishi: The basic process is that as an artist, I go into pitch darkness without vision and draw with light on photo paper. The color darkroom is fully dark and the images are made with a flashlight actually burning the paper. It becomes conceptual and political, and there is this beautiful promise, or dream, that you go through darkness, not able to see anything and you have full freedom to do anything. Questions come up: Are you going to paint your dreams? Are you going to paint your fears, memories, desires? Ultimately, I am interested in how I can play with that situation, how I can politicize it, how I can conceptualize it. But also, in some ways, this photographic process of making the work with a flashlight could be seen as being really cheesy, like how sometimes photography is called “painting with light.”

RL: But you are literally painting with your flashlight.

HF: Exactly. I am actually exposing the paper and painting with a flashlight.

RL: What are you painting? Your dreams? Your fantasies? Or are you telling stories?

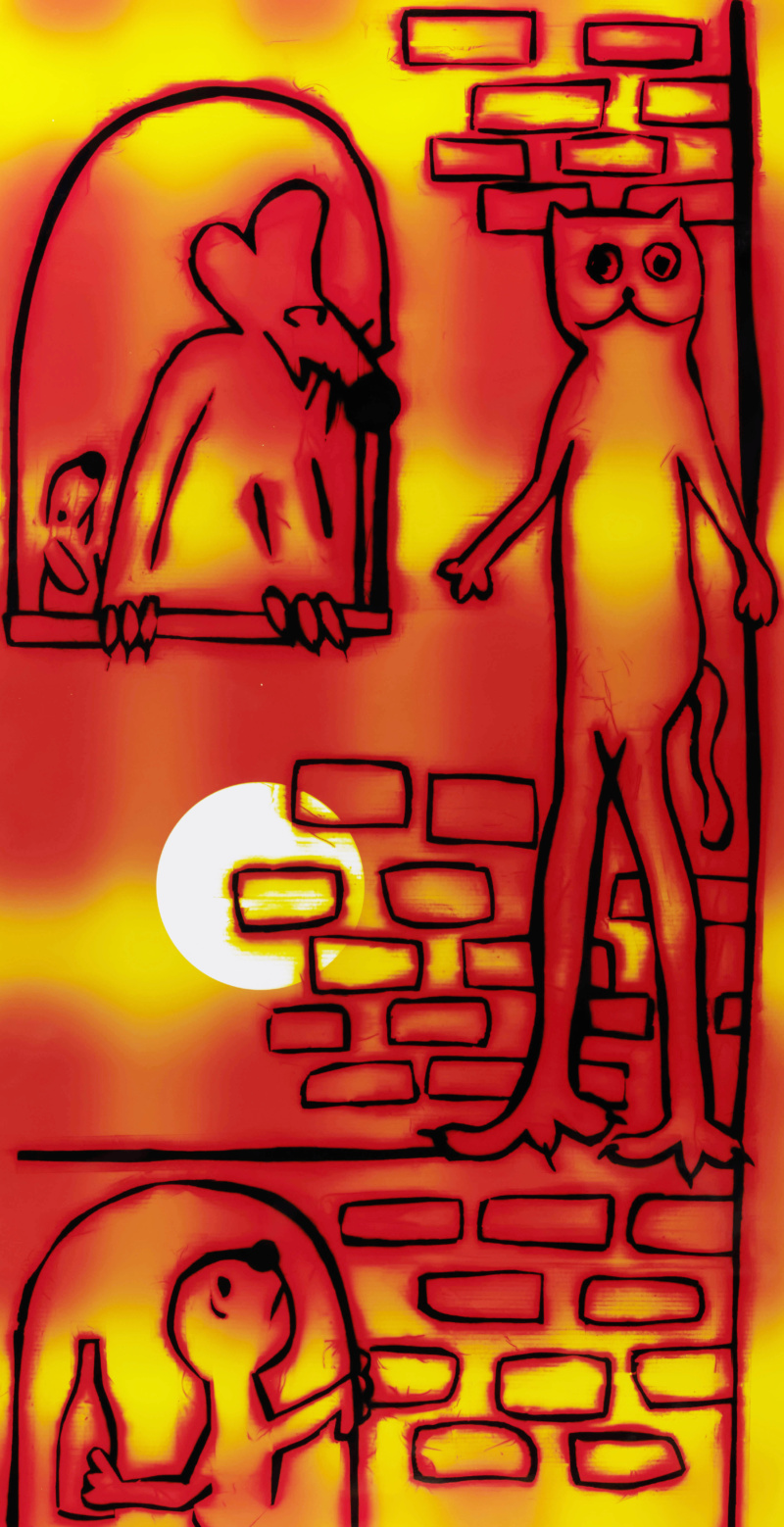

HF: I think none of those and all of those, but I am not doing any of them. I use the human figure and animals to create a visual language within the works, knowing that a viewer subconsciously will look for a storyline. I consciously avoid any narrative structure, but am aware that the repetition of form and figure will send a signal to the viewer that there might be one. In this way, all the figures are treated in a formalist manner, whether it’s a human, a cat or a mouse hole—these elements are treated as forms within a larger composition. To be clear, the rat, or cat does not stand for something specific, but altogether each time, in each work, in relation to one another these forms point to so many things. I don’t have much interest in taking an audience to simply come sit and see my dreams so I decided to make work that would allow the audience to project onto it: you look at this image and you spend some time to see what is happening. As a viewer, you end up completing the story or giving it a story and all these possible scenarios come through because of the way the work is operating between the author and the audience.

RL: It’s open-ended but then there is a certain specificity that you create?

HF: I’m conscious of the images I’m making. I think there always has to be a mix of freedom and full control, so the control I have is that while I’m free to do whatever I want in the darkroom, I’m going to twist it and mess with it. In this body of work, I’m just using four components: a human, a dog, a cat and a mouse. Between these four, subconsciously, we think that one deserves more power than the others. I consciously switch their positions, so normally if a boat in a waterfall is going to be capsized and wrecked then it’s the sailor that’s going to save the boat and not the dog but here the dog is the one that is dragging the boat to safety. By switching the power play, it becomes symbolic and starts referencing other things in our lives.

RL: You have very interesting titles for your work. Does the viewer get all that information from them?

HF: I try to play with the titles, too. But these are issues I feel as a thirty-year-old person in America; I’m not forcing the audience to receive or understand a particular set of information because that’s not the point. I’m putting these ideas in the work and then allowing them to be received and interpreted and projected upon. I grew up within a totalitarian country and they really tried to force us to see everything based on their perspective and that’s clearly not the way. It’s a visual experience and then the hope is that maybe your mind can be changed. I think it’s possible that you will enjoy the show a lot because you might find it beautiful or cute or funny and then maybe later on someone will write about it and that text will also open other doors to it and describe it as ugly, irritating or inherently sad and you might still like it.

RL: Is there anything specific about these colors that you’re using?

HF: The color of each work is almost entirely based on chance. My belief is that when you allow chance to play a role you are choosing to give up the idea of perfection, accepting that it might not be perfect.

RL: Your works are unique. They’re kind of like happenings.

HF: Yes, it’s like a performance happening in the darkroom but it is private; it’s a one-person performance and the viewer can’t see it. Even if the viewer shows up in my darkroom they wouldn’t be able to see anything because it’s happening in pitch darkness. It’s made 100 percent without a visual sense, but the sense of touch is there. And time is there; they often take upwards of six or seven hours of darkness to make. Often, I won’t see the result for a couple of days, not until I chemically process the photo. For me, this delay is a privilege as I am aware that probably if I could see the result right away I would want to remake it, and I don’t think that’s the best approach to art making.

RL: At the show at Petzel Gallery, you have to walk up to the installation and look inside. Do the installations that you do around the photographs illustrate what is in the image or just to add to it?

HF: It’s an extension of the work in the three-dimensional world, and it allows me to play with the idea and understanding of the position of the viewer in the room. For the piece I did at Petzel I made a figure that was placed within the work and from outside there was a feeling of wanting to see inside the installation.

RL: To me, there’s a lot of violence in your work. Is that your humor or is it tension?

HF: I don’t think that the job of an artwork is to make you feel good, I feel like it should bring some questions or make me feel uncomfortable. You know people have become so comfortable with seeing cute, beautiful or happy art. I would not say my work is violent, but instead that it alludes to violence. I’m not placing an actual bomb in the middle of the room, but still there is a feeling that something has happened here, that something could have been blown up. On the other hand, in my work there is this sense of territories being agitated somewhere between satire and stereotypes. I want the viewer to have room to experience different types of emotions: superiority, discomfort, identification and alienation.

RL: To me, without it, it would lose a lot of power. The work is all about the tension.

HF: It becomes more clear in the sculptures, because the viewer subconsciously gives a body to the sculpture. But, in reality, this photograph is also made through a kind of brutal act: I burn the paper; I walk on it; I’m not being gentle with the material that usually is very delicate or treated very carefully.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.