“The spaces Black people inhabit are at once physical, immaterial and carried thru our bones, thru time and back out into the world thru velvet, wood, lace and plastic. Devin N. Morris prefers glass. Thru drawing, collage, sculpture and a variety of works that swing between those spaces, Devin N. Morris provides us with a look at the entirety of a language at once gay, Black and deeply personal, while maintaining a familiarity that makes his grandmother’s house in Baltimore feel like my grandmother’s house in Westbury, Long Island. How do you create a home to live in when the idea of home is an idea that lives in your bones? What do bones look like when wrapped in lace and how do the spaces we are afforded affect our attempts at materializing the immaterial?”

—Azikiwe Mohammed

Azikiwe Mohammed: Can you tell me a bit about your last show, “Play Too Much,” at Company Gallery’s Baby Company space? Seeing it in person I was struck by how the entire show presented itself as a protected space.

Devin N. Morris: Once I made that space, it felt like the center became a public environment while the perimeter became more intimate. The chairs that were grouped in the center pushed you up against the works that hung on the walls. The various fabrics separating the chaired interior from the wall works allowed the viewer to stand back, almost as if in a different space, while still interacting with the entire installation.

AM: I don't feel that natural push and pull in galleries very often.

DNM: Right. I went to see a lot of shows before “Play Too Much” opened and there’s this strange occurrence where all this work concerns itself with identity, but the gallery feels so stark that nothing can really populate; when I went to St. Louis for “Soft Scrub” at The Luminary I was thinking about these relationships within my legacy—the relationships within my family and the spaces they hold.

AM: Your family is from Baltimore, yes?

DNM: Yes, my family is from Baltimore. I was looking at how I could make a living room that's also a gated area. I created a living space that you can only access from a distance. The intimate act of staring out the window.

When I was on the phone with the curator for “Soft Scrub,” Katherine Simone Reynolds, she asked if I would be bringing the chair installation for that show. I told her that it took ten years to compile the chairs for “Play Too Much” and I had since gotten rid of most of them. At the time, I felt done with the desire for the presence of those objects, as more recently I've been drawn to doors. I did this performance last year in SoHo at Agnes B. Gallery for their “Auto Body” show. As part of the show’s programming, two of the artists who participated in the show, Hayley Martell and Asa Thornton, invited me to take part in a happening—a night of performance. My performance and resulting sculpture is titled Four Door Coup. I kept thinking about me not necessarily being a performance artist but if I don't think of it as performance then it works for me. I challenged myself to see the performance as a personal act of care. I questioned; what does it mean to build a space? What am I going to do in this space? The end result had me building a room out of four doors and dressing two of the doors from that sculpture with curtains for privacy and tending. I realized I wanted a space for privacy, as I think a lot about the performance of self and how even in domestic spaces we are confronted with the need to create a projection of the self. In the environment I created, I had no one to show up for—it was just me in my four walls.

https://vimeo.com/447870020Bushes Low, 2019.

AM: All of the objects and experiences that you are speaking of feel like they live in the same family, both visually and viscerally: intense feelings of intimacy from afar, your body living inside a space that was built for it—but maybe for a different version of it, a version you are in constant negotiation with. This to me feels like some of the realities of being Black in America.

DNM: It doesn’t matter what I do in the space I built for Four Door Coup, because ultimately that space is entitled to me. I made it for myself, and as such I don't have to define how I use it.

AM: When sitting in the chairs at “Play Too Much” and looking at another person (and even when there is no other person in the room at the same time as you), when going to look at something behind me (the viewer), instead of getting up to do it, I would stretch my arm over the chair to peer over at the work behind me. This is an action I take in my home. Now you have fully placed me in a home. I try to put chairs in as many places as possible where I am showing work to allow for this possibility, because it forces your body to be part of the viewing process, not just your eyes.

DNM: Chairs are performative objects. Objects that can make you believe. A chair makes you think about being supported. As well, the viewer could give in to the chair and do the thing that it's calling you to do: sit. To be still. For a long time, that's what I wanted that environment to beckon. Maybe I spiritually needed that kind of access. These chairs provided me a space to hear, the works a chance to speak, and welcomed the viewer to come in and do both.

AM: Because we don't have that, right? How many times has a security guard come up and said something to you while you watched them say nothing to anybody else?

DNM: All the time. Even though I will say now, in museums, I've been having good conversations with security guards where they're able to speak about the work or about the wall text and be like, “I don't believe that this is what the artist is trying to convey.” They spend these giant chunks of time with the work. Often during our exchange I will ask, “who's the curator?” Maybe I can talk to the curator as I have more questions. Look, whenever you find out who is behind the curtain you can talk to them. They’re just a curtain away.

AM: How long have you been in New York?

DNM: Going on 10 years.

AM: Okay, now you're local. That's the rule, right? 10 years?

DNM: Yeah. And that's probably what sent me into the emotional arc I went through in 2019, realizing, "Am I a New Yorker? Do I relate to these ideas of New Yorker-dom?" I don't know which side I came out on, but I know I questioned a ton of other things truly about my relationship with this place, which has been my home, but can New York ever be my home home? I don't have roots here. I can't go to my families’ houses. I don't have any memories of high school or memories of my youth here. New York is where I came primarily to learn how to work. If I had kids, I could be more present in New York in a way I haven’t been able to yet, which would make me more indebted to the city.

AM: When I think about kids, I think about physical scale. Imagine everything as five times the size of you. Walking right under a chair. Choosing to get on it or just go right under it.

DNM: That kind of wonder is a wood-shingled roof in Baltimore. Walking past a dump truck and feeling entirely too small because you're smaller than its tires. New York and I don’t have the same relationship to memory just yet.

AM: But I think that a lot of the work you make does.

DNM: Yes. It’s creating a window, a portal of sorts, but then placing things in motion as if they are on their way out of the space because they could fall out, or they've been projected into the space. I love thinking about the relationship to that feeling of movement and picking up pieces of memories as they swirl around and within me. I work at a scale now where objects can be collaged, which I think adds to the power of their presence.

AM: I’ve heard you mention queering space before; what do you mean by this? Do you feel that happens as much in the flatter works as it does the larger sculptural works?

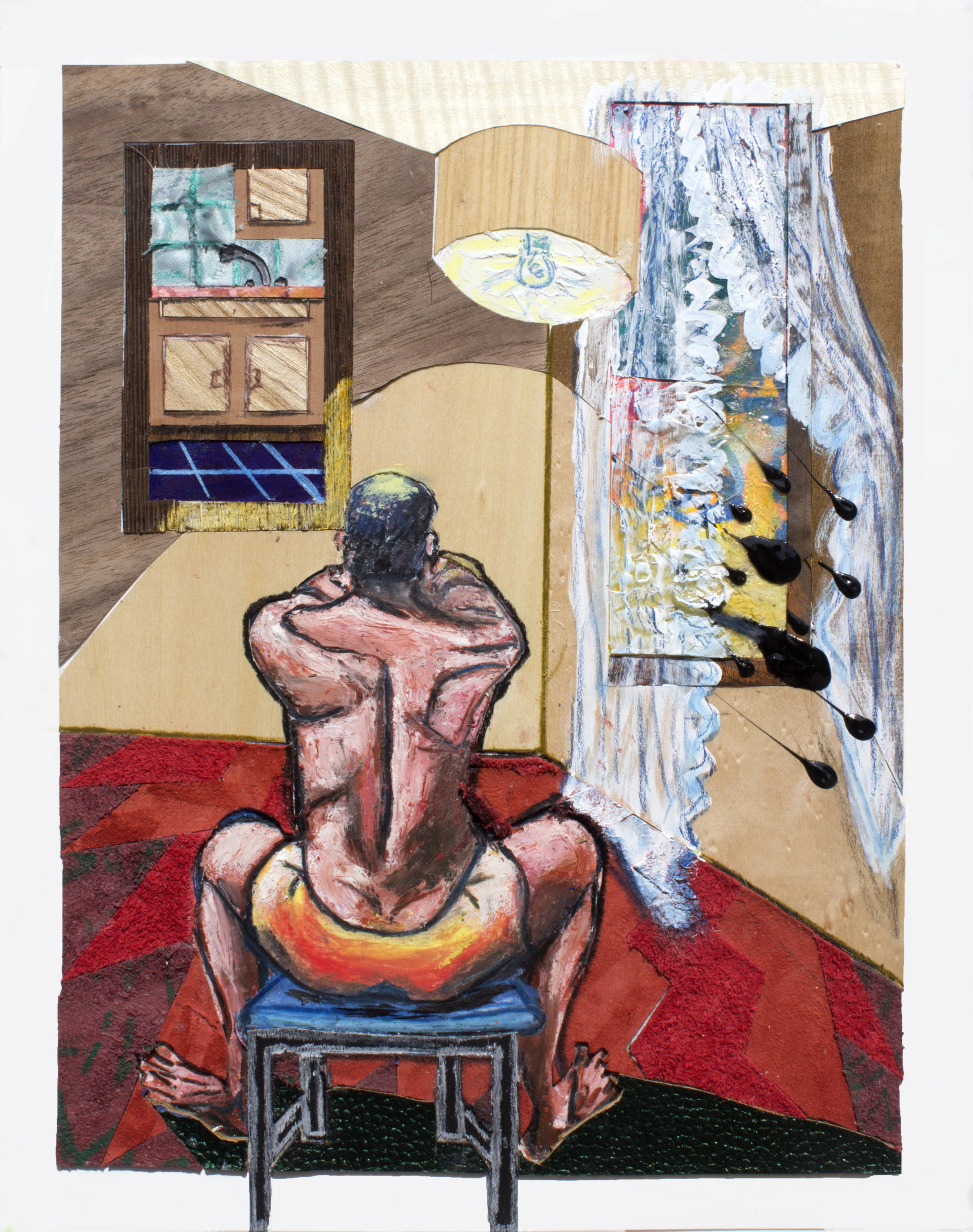

DNM: I feel like it might happen more figuratively in the wall-mounted collage paintings. I typically depict acts of kindness, acts of care between men or genderless bodies. As well as taking physical objects and realigning their purpose or how they are remembered by their inclusion within these works, the spaces that all elements of the work are in tension with are queered, peculiar and hopefully provide access to a feeling of transcendence.

AM: Is this the departure point for the work in the New Museum show, “Transgender Hirstory in 99 Objects” as part of “MOTHA and Chris E. Vargas: Consciousness Razing—The Stonewall Re-Memorialization Project” from 2018?

DNM: Right. The work for “Transgender Hirstory in 99 Objects” was a way to answer a question from a different perspective. I worked at a tiny scale, which I feel helped me focus on the importance of the sculpture and encouraged the viewer to look closer.

AM: What was the question?

DNM: The question was how to re-commemorate by making new sculptures for Stonewall Park: to propose monuments that sought to illuminate the Black and Latinx trans women whose work and efforts began the LGBTQ rights movement. Chris E. Vargas invited me to take part in the exhibition. He is the founder of the Museum of Transgender Hirstory & Art (MOTHA), a semi-fictional, transient institution that serves as a platform for exhibiting trans history and cultural production. I designed and created a line of chairs that would replace the current sculptures in Stonewall Park titled A Seat For Sitting. Each chair honored a different trans activist or creator who helped widen the visibility of trans bodies. The line centered domestic comforts, as I wanted to uproot the uses of this very traditional public park.

I don't really relate to Stonewall as a place, but, for the 50th anniversary I was invited to be in this show. I thought of the experience of the West Village—how some people have a very Black and queer relationship, if not with the Stonewall Inn, then to nearby Christopher Street and down to the piers. I spent some of my early days in New York in the village and back then it felt like a haven. But there is something about mainstream gay culture and its whitewashing of Stonewall that doesn't fully vibe for me.

AM: As somebody who works across a very wide variety of mediums, do you find yourself taking lessons learned from the last work made and applying those things to the next circumstance/creation?

DNM: Yes, but often it is less of a lesson and more of a feeling, an emotion or a form of emotionality that is reached and then can be applied again. To make a work, I must understand what draws me to do it, and then it teaches me over time, over the years. As those years pass and I accumulate more understandings, the time passed allows me to experience other people who might deal with a similar kind of concern. Making is a largely spiritual process for me and I listen very quietly to know what needs to be added to my understanding of working with objects and surfaces.

I think of Blackness like a family myth. I know I'm not the only one going through it. I know it's different in every household. We know that each Black person can more specifically identify how this happens for them/us as we familiarize ourselves with each other's families’ tales. But, like my use of that door, this isn't my door. It's everybody's door. We all got doors, we all got clocks. We all got walls.

AM: Visual language.

DNM: Yes.

AM: There are certain things that you will find in our homes—Black homes—that you won't find anywhere else. There are some things I need to explain to certain people that I can't explain to others because they don't have that shared experience. If you haven’t been in that room, you haven’t been in that room.

DNM: Everybody knows a door, everybody knows a certain care that goes into these homes. We are the IKEA generation. We are a post-HGTV generation that had to reinvent how to do your house. We had years where people weren't really renovating, just buying these pre-fab pieces from IKEA that act as sets. They act as an idea of a home without one having to make the decisions one would have to make when building a home from scratch. IKEA and HGTV made it so you could buy a language, but Black folk already have a language. A language we fought for. Our renovations exist within our bodies.

AM: Renovation within walls and we are the walls.

DNM: There was no changing the space. It was buy a living room set, buy a dining room set, because that also spoke to how much legacy is present in our environments. The legacy we are denied in public we build back into the Black home. The thing about Americanism is, we can all identify as American, but, within that is a wide variety of visual languages, many of which are object-based. Sometimes we have objects changing over and becoming vulnerable (removed from domestic use) to natural environments (found in nature). Some of these objects live primarily outside—I call those natural objects—but once moved inside they become natural domestic objects. Natural domestic objects should be protected by walls and roofs so they don’t rot or age. A chair shouldn’t be rained on, but, if you move it outside, it becomes natural and then it becomes vulnerable to nature. You have to allow for an object to exist in both spaces.

AM: The way you invite people into the spaces you build allows them to live alongside, but, at the same time, inside of something. You make that duality natural.

DNM: I love dualities and juxtaposition. Also, I like to mentally and physically alter how a person feels when they are near my work. I think that speaks to the feeling of living alongside and inside of the experience at the same time. The viewer is immersed but also a part of the work. For instance: when a memory is too viciously recalled, when I can't get away from the feeling of it, because I always feel like I could cry at any second, tears growing from the weight of mourning, processing. I carry loss. I'm dealing with that as I make the work. People deal with many losses, whether it be the loss of a physical life or one of the many other ways that things just exhaust themselves. I don't know if it drains me to work through mourning, but it might drain you. I'm working through it, I'm giving it away. As much as the object is there to remind us of our human physical experience, spirit is also present and my intentions are for these intimate spaces to speak to how we’ve lived and provide a space for contemplating our relationships to things we need to learn from or let expire within our lives. I see duality in how I see death, which is a celebration, or how I see love—if you love something, you have to love it in all its forms. In life, death and the liminal spaces we inhabit between these time markers, you gotta let it be. If you truly love it—and not a capitalist love, which is much closer to romance—a love that lacks the capitalist mentality of ownership. I'm not trying to romance you. I want to make work about the actuality of love which, for me, is about freedom. Love is a state I'm happy to inhabit.

AM: Standing between the glass framed doors and under the chair of the work titled, Moving away from up there. Broken easily as brown skin does walking through brown stone. From Somewhere and Me at the base of stairs treading rows perfectly soiled for blossoming lunacy, from your show “Noplace” at P.P.O.W. Gallery this summer, the viewers trust you in a physical way that has always been part of the work but less spoken about. Can you speak to the shift in a more direct ask?

DNM: I love how you phrase the experience of standing under that doorway as asking the audience to trust me. That is something I had to ask of myself, if building this doorway made of doors would work, as I could not physically lift the work or fathom how I would construct it. About a year ago, I drew the idea for the doorway with the chair lamp on top and I knew that I was creating a communication with a feeling. Thinking about bodies in transitional states; life, living, death, spirit and the physicality and performative presence of a door (opens or closes, provides access to a barriered region that you must traverse the door's threshold to access), each door with its great paned window provided a slippage, a view to the other side. The potential for panorama and a variety of physically temporal possibilities. I wonder if the viewer feels that they need to trust me, or, if in that moment where trust needs to be exercised to walk through that threshold, is it then that the windows with their provisions of access might trick the viewer into a sort of belief that is bigger than trust in me? I want you to believe that you can and should engage in this experience.

AM: A lot of the work says 2020—was this made during COVID quarantine and, if so, do you feel that has any bearing on the work?

DNM: The wood veneer collages were made during quarantine. Those collages and thinking through using wood veneer, intarsia, leather, knitting, puzzling and mixing those materials and processes with more traditional mediums like oil pastel and acrylic helped me think more intentionally about surfaces. I can now see any object and turn it into a surface or puzzle piece that can, once included in a larger grouping of surfaces, create a new surface entirely. A fabric, a family, a Black life is a collage. That's what 2020 helped me make sense of, the ways in which the many different mediums I work in come together as one larger framework. A breaking of any constructs of form that I believed I needed to align with.

AM: I know a lot of your works live as drawings, first, before they become more fleshed out. You mentioned going to technical high school in Baltimore; has that influenced your practice? Has that helped this breaking of constructs in relation to form when your drawings, collages and sculptures all share the same space?

DNM: I attended Baltimore Polytechnic Institute. On my first day there I was late because I took a Hack and it got into an accident. Hack was essentially an early form of Uber for us in Baltimore. It was a way of ride sharing that is similar to hitchhiking, but for shorter distances, and there were understood rates for the distance you were going but you could haggle a bit. On my first day of school we began learning about bridges and drawing what would become models for bridges. Poly school focused on engineering and science. I studied engineering, as my dad had when he went there. What I learned was to see to the end of any process of building in relation to structure. If I can imagine the process that it takes to build something, I can also take it apart, which allows me to draw an image of an end point and then work backwards from there. I was always a builder and, as a kid, I could be found creating my own play environments everywhere. I had my bedroom where I played, building house structures and parking lots, my basement where me and my siblings’ toys were, my grandparent's house and a tree house. I had many places to play and expand and no one stopped nor questioned my play. Growing up, they told us we could be anything. Through the play of my childhood, I became every idea of a person I could imagine. I built coffins for birds out of old shoe boxes and held burial ceremonies for them. Most of the ways I hear are through my hands and that knowledge was passed to me from my mother, grandfather, father and grandmother. Those are the people I watched and developed my understanding of the world through. That is the knowledge that lives inside of the objects and spaces I create. I hope that some of that knowledge can be passed to the viewers and that they can continue the chain.