On the north side of Delancey and Clinton Streets, where the Williamsburg Bridge starts to slope upwards from New York’s Lower East Side towards Brooklyn, is an inconspicuous storefront whose awning reads Rainbow Shoe Repair. Nothing about its appearance would suggest that this tiny shop had once also housed a photography studio in addition to the services advertised on its signage, which currently include key copies, zipper replacement and shoe shining.

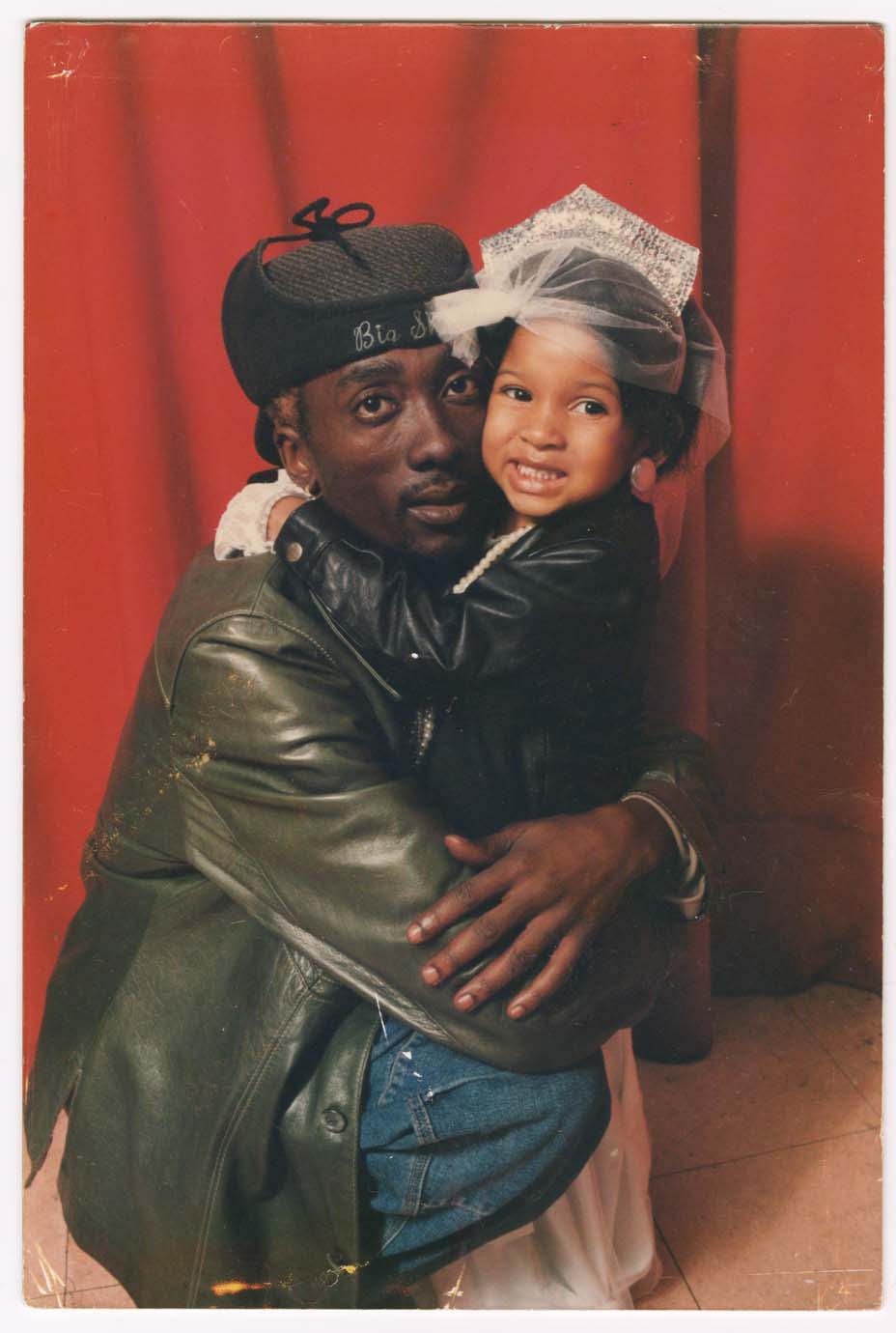

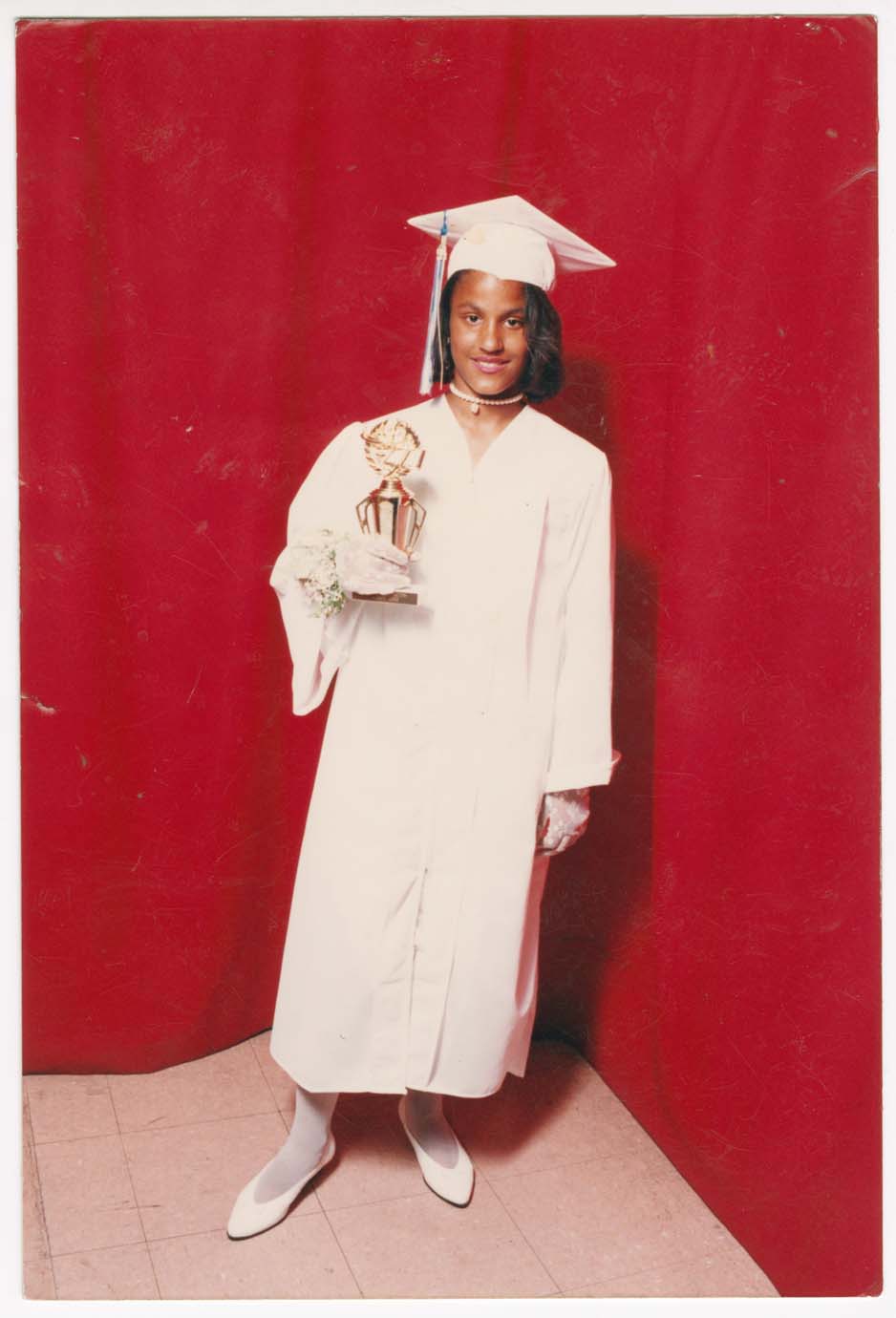

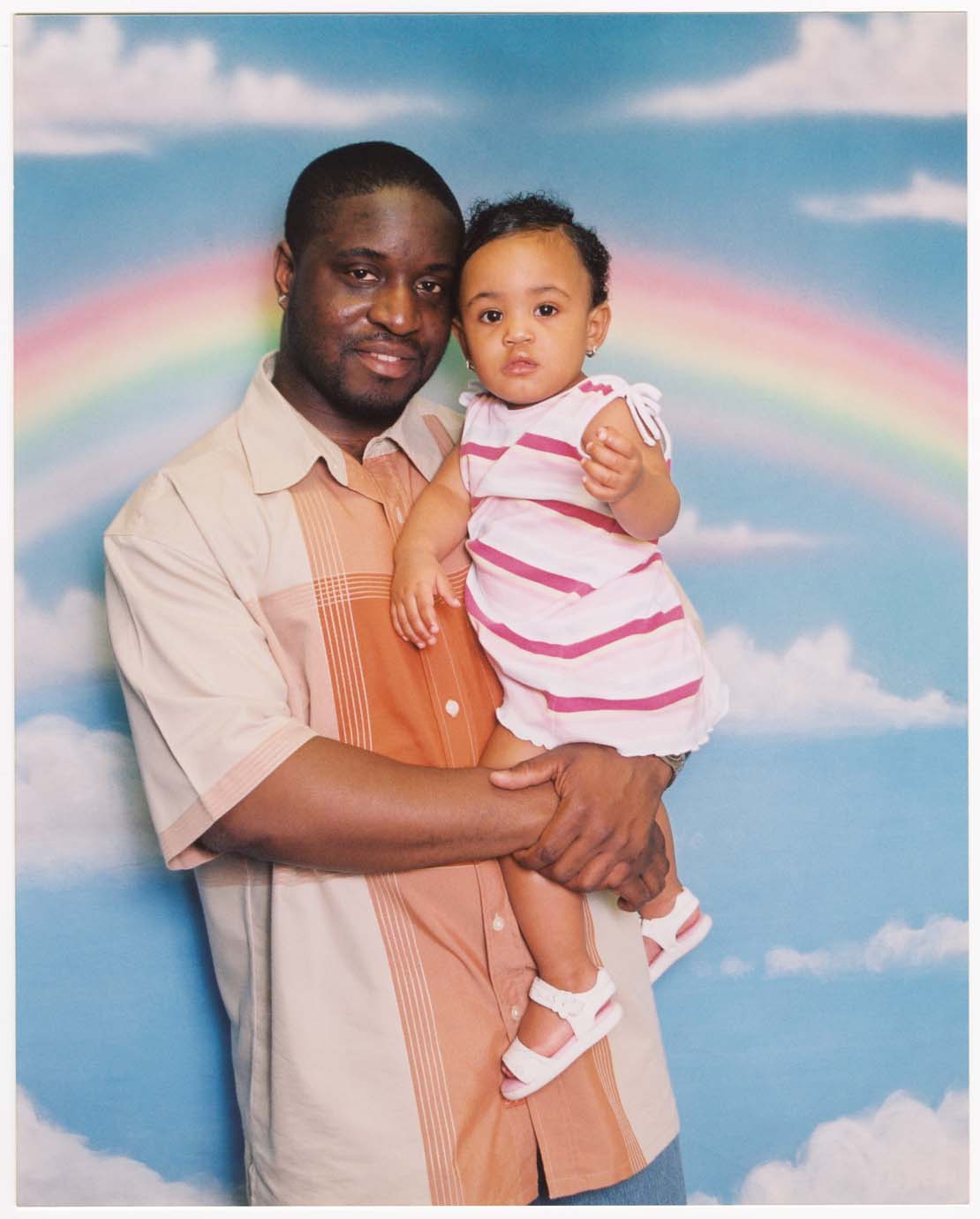

From the mid-1980s to the early 2000s, residents of the LES visited Rainbow Shoe Repair to have their portraits taken—most staged against two signature backdrops: one a blue sky painted with a rainbow and wisps of cloud; the other a deep crimson. The occasions for these sittings ranged from coming-of-age milestones (baptisms, graduations, etc.) to spontaneous drop-ins precipitated by a special outfit, a fresh haircut or the simple desire to have one’s photo taken (remember, this was pre-digital, pre-cell phone, pre-social media).

This winter, Abrons Arts Center (a multidisciplinary space within the historical community organization Henry Street Settlement) is exhibiting images created during Rainbow Shoe Repair’s almost-three decade run under three consecutive operators—Joseph Borukhov, Ilya Shaulov and Anthony Allaev—each of whom also served as the resident photographer at the time. “Rainbow Shoe Repair: An Unexpected Theater of Flyness,” curated by Abrons’s Director of Programming Ali Rosa-Salas, fashion historian and former Gucci educational consultant Kimberly Jenkins, and curatorial fellow Brooke Nicholas, unites roughly fifty images uncovered in the shop’s storage.

The show has an unusual origin story. Two summers ago, Brooklyn-born Rosa-Salas and Bronx-native Sammi Gay were paging through a family photo trove, reminiscing about the New York of their not-so-far-off childhoods, when they came across a handful of portraits of Gay’s parents taken against a stark red background. Fascinated by these unusual portals into another time, Rosa-Salas made plans to visit Rainbow Shoe Repair, still located just a few blocks from Abrons. It turned out that boxes of prints and negatives remained in the back of the shop (now fully dedicated to various repairs and the occasional passport photo), many of which had never been claimed by their respective customers.

It might be incorrect to call this collection of images an archive. It is, rather, a practically accidental repository of material culture that, until quite recently, probably wouldn’t have been considered relevant to the records of art institutions or libraries. The discovery itself was more akin to archeology: the miraculous uncovering of what might otherwise have slipped through the cracks of history. Abrons purchased a selection of the unclaimed photographs, setting in motion a complex endeavor to create an exhibition that would honor and memorialize the studio and the many LES residents who were photographed there.

One of the biggest logistical and ethical challenges in framing the material evidence of personal lives in an art context is consent. Unsurprisingly, the curators were not able to identify or contact everyone pictured in the images—landlines are disconnected, addresses outdated, lives scattered across New York and the country—and grappled throughout the planning process with how to consciously manage the balance between protecting individual privacy and illuminating a crucial collective history. “There’s always a risk, with any presentation of visual culture, to miss context,” Rosa-Salas comments. They spent months crowdsourcing information from people in the community. A crucial element of this investigation was an open call, in which fliers were distributed in the neighborhood and online that invited people to submit photos taken at Rainbow or to share memories about the space.

Submissions trickled in. Some faces were identified, others were not, but the thread lines that did emerge began to reveal what this place meant and to whom. As Gay’s father Elroy, a community organizer, designer and founder of Tha 6th Boro, Inc., explained in a research interview, “If you got your picture [at Rainbow], it was for bragging rights. Everybody wanted a picture and there weren’t a lot of cameras floating around at that time. If you both looked jiggy that day, you would take a photo. If you had enough money, you’d get two.”

If you know anything about the LES (or the New York in general) of that era of immense creative innovation, you can already imagine the electricity of these images: the intentionality of the clothes, the accessories, the square-tip acrylics, the spotless kicks and gleaming pendants—style like you wouldn’t believe. These photographs bear witness to the LES’s layered history as a fashion hub—from mom and pop specialty stores on Orchard that sold everything from hats to custom suits, to jewelers and pawnshops on Clinton, to Jimmy Jazz (the iconic sneaker retailer’s first NYC location on Delancey opened in 1988 and closed in 2011), Richies and Fabco. They also pay particular homage to the cultural practice of getting fly. Being fly isn’t the same as being fashionable. Flyness—just as much a way of living as a way of looking—has little if any relationship to our contemporary understanding of what fashion is. While the apotheosis of high-fashion chic is a kind of effortlessness, getting fly is anything but. It is boldly intentional and defiantly earnest.

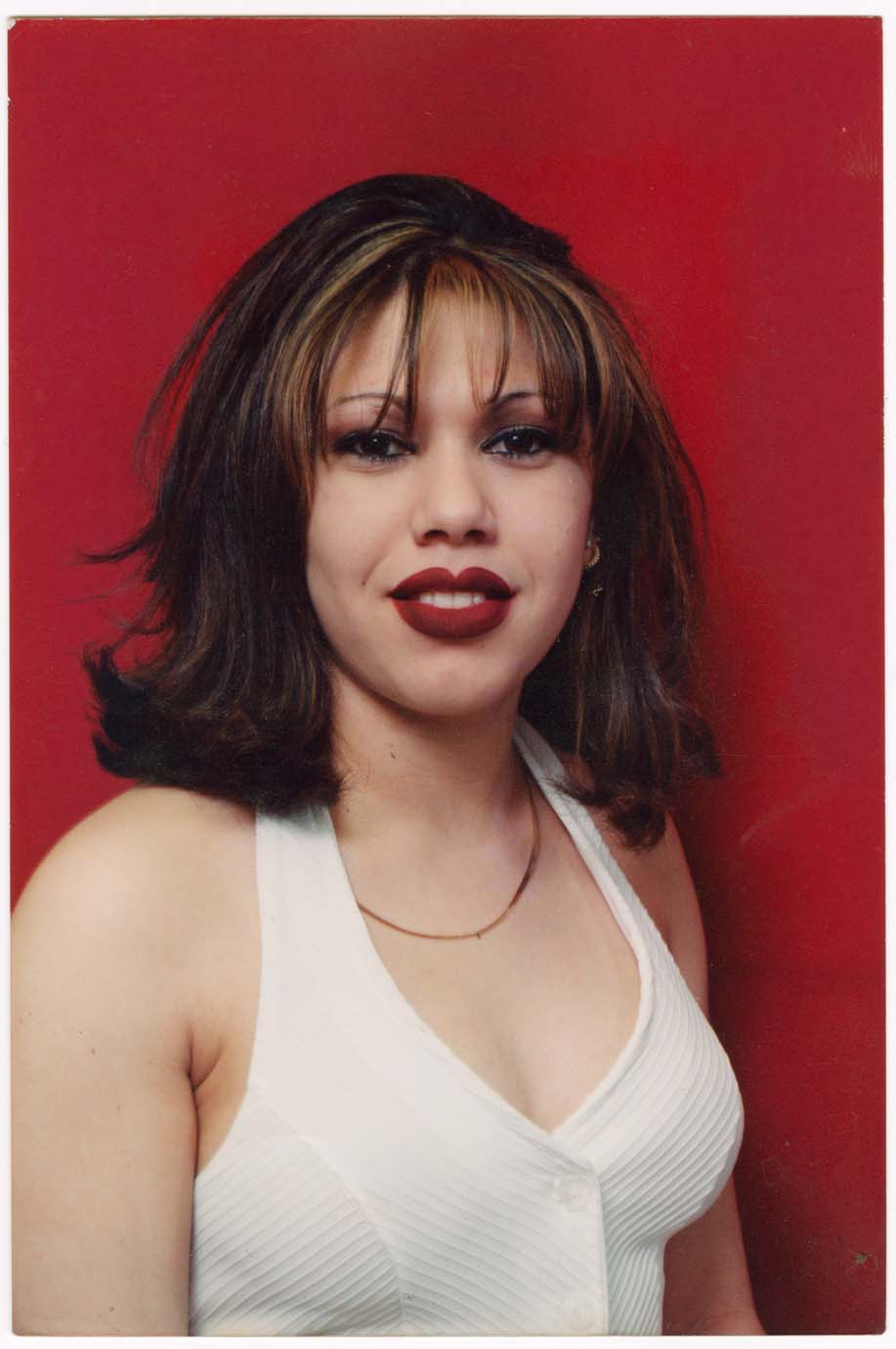

In one photograph, circa 1998, stripes of platinum glisten in the bangs of a woman named Yesenia who lived above the shop at the time this portrait was taken, according to the photo’s owner, childhood friend Shawntel Dunbar. Her super-thin eyebrows date the image, as does the flip of her blowout. She wears a white tuxedo-style halter top and a delicate gold chain. Her precisely painted smile matches the red of the backdrop near perfectly.

In another from 1996, Shawntel poses against the rainbow backdrop, braceleted wrists and manicured nails gracefully crossed over her right thigh. Her impressive updo is embellished with twin butterfly clips, two careful wisps framing her face; she shared in an interview with the curators that she got her hair done that day in Jamaica, Queens. She wears a black skirt and matching hooded vest. A frosty gloss coats her lips and a nameplate shines around her neck. “I was working in corporate America at the time,” Shawntel remarked of her two-set. “I really wanted to dress the part—I wanted to fit in but I didn’t want to take away from who I was.”

This statement reveals a critical self-awareness, as she describes her choice of clothing as a means of creating an identity that will allow her to navigate between different cultural realms. The powerful intentionality of these images is part of why they still resonate today, as so many people in America continue to struggle with the fundamental duality of fitting in without losing yourself.

On a cold day in late November, Rosa-Salas and I visited Ilya Shaulov at his apartment in Starrett City, Brooklyn. The three of us sat in his dining room as he recounted the nine years he spent running Rainbow from 1997-2006. Shaulov grew up in the former USSR and immigrated to New York in 1992, living for most of his adult life in Queens. He is one of nine children and three of his older brothers had been community photographers back home. In the US, he worked whatever jobs he could, starting first as a yellow cab driver while he learned English in night school. We laid out a selection of photographs on the tablecloth’s clear plastic cover. His eyes creased into a smile as he recognized faces he hadn’t seen in two decades yet remembered in surprising detail. The people in the images had not yet been identified—for example, two tweenaged girls, possibly twins, standing back to back, clean white Pumas beaming in the camera’s flash—and Rosa-Salas was hopeful that his memory might lend some clues.

Shaulov explained that the LES of that time was a tight-knit community, not despite of but because it was so diverse. He remembers a distinct neighborhood creativity and solidarity, fondly referring to the area as “the 6th borough” and echoing sentiments from conversations with Elroy Gay. “In my neighborhood on Avenue D, one thing about us was that we all loved to dress. We were picture-ready always,” Gay had observed. “For some reason, our style is so different. Hot 97 used to shout out all the boroughs, but they would never shout out Downtown. Lower East Side—the 6th borough—we are our own borough.” Shaulov worked at Rainbow for eleven hours per day, six days a week, closing only to observe Sabbat. He ran the shop with one other man, who handled the shoe repair, but Shaulov learned cobbling too so that he could cover for his colleague if need be. This spirit of resourcefulness and horizontal collaboration came up several times, a detail he seemed to feel epitomized those years.

In the LES in particular, popular historical narratives tend to focus on European immigration and the mythology of the melting pot, as well as on artists who settled in the area in the ’80s. Though these plotlines are essential to the big picture, the curators emphasize that Black and Latinx people are often missing from the neighborhood’s place in popular consciousness, both in terms of the physical space they occupied and the immense creative legacy they left. In sync with our current cycle of retromania, the hip-hop and sportswear-style clothes in many of these images actually look contemporary, but the specter of gentrification casts a dark shadow on what fashion puff pieces might package as to-be-expected ’90s nostalgia. Few may readily know, Rosa-Salas tells me on a conference call with all three of the curators, that the LES was once a center of garment manufacturing, some artisans and manufacturers relocating as recently as the early ’00s. That many of these images are barely 20 years old does not make them any less historically impactful; “The show reaches back into the LES’s most recent past, keeping it relevant during times of change,” observes Nicholas.

One of the exhibition’s promises is that it will spread awareness of this history throughout the city—and in one sense, literally so. At Abrons, some images hang in the foyer of the exhibition space; others are enlarged to the size of posters, in collaboration with United Photo Industries, and pasted on the exteriors of Henry Street Settlement buildings around the LES, from “up the hill” at the southeastern most tip of Manhattan all the way along Loisaida and Avenue D to 14th Street. These outdoor displays (all of which have been consented to by the sitters) are strategically placed at sites such as Martin Luther King Jr. Community Park (adjacent to Henry Street Settlement’s headquarters), Boys & Girls Republic on East 6th Street and Workforce Development Center on Broome Street.

“This exhibition comes at a really good time,” Jenkins adds. “Dapper Dan is getting all this shine and recognition for the space he carved out Uptown; likewise, on the opposite end of the island, people were creating their own space, too.” The images from Rainbow Shoe Repair, and the stories that accompany them, articulate the urgency of those practices of cultural production often taken for granted: the clothes we wear every day, the records we create to memorialize our personal achievements and private joys. These vernacular forms of expression and style are the underpinnings of complex and tenacious ecosystems that flourish outside of the now-global industries that we have come to call “fashion” and “art”—industries predicated on capitalist metrics of value, ownership and exclusion.

The drawing of the psychic territory of the past is often left to the bureaucratic apparatuses of formal archives and elite institutions, fashioning selective and distorted histories mandated by those with power. “A huge part of Rainbow’s appeal is that it was such an unconventional space,” Jenkins says. “It captures ingenuity and intention.” And indeed, the ways that both individuals and communities insistently document and preserve their own lives and stories have, as of late, been increasingly studied and heralded—not only for the light these efforts now shine on the past, but for the lessons they offer about the existential wars that continue to be waged in New York and in cities all over America. It is but one responsibility of this publication to look closely at what comprises the slippery term “culture,” a word historically weaponized both to alienate and to entice.

Another goal of the show is for the images from Rainbow actually to be returned to their owners, some of whom may still live in the neighborhood. Perhaps these reunions will trigger the synapses, snapping into focus days and nights long forgotten, friends out of sight or mind. “A photo is a memory,” Shaulov remarked as Rosa-Salas and I stood up from his dining room table, about to say goodbye. “Once and a while you sit and look and you remember that time is passing.”

Rainbow Shoe Repair: An Unexpected Theater of Flyness is at Abrons Arts Center through March 29, 2020.

in your life?

in your life?