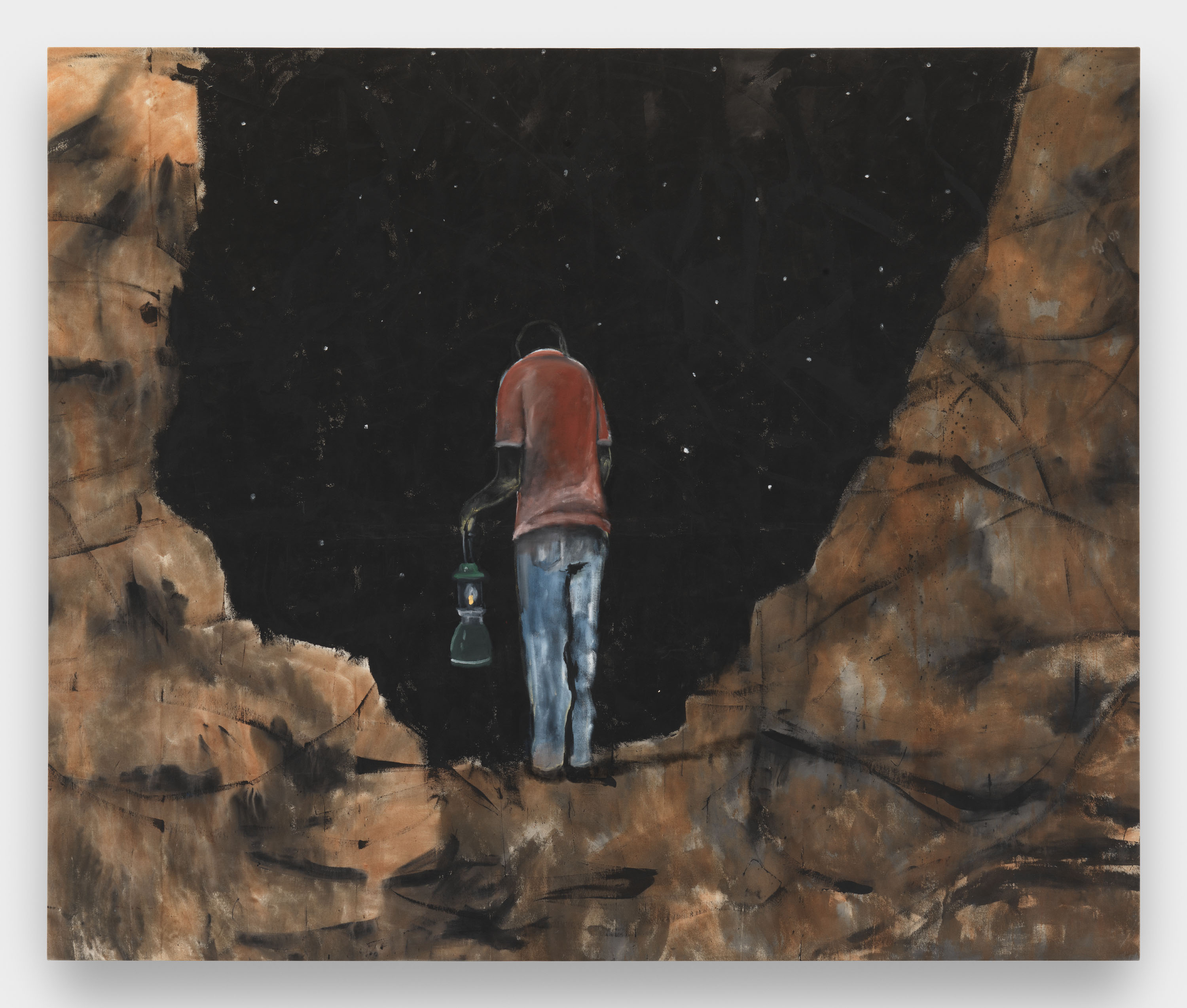

“I don’t want tragedy to be the frame through which you see the work,” says superstar curator Helen Molesworth, standing before Noah Davis’s 2011 Painting for My Dad, a seven and a half foot wide canvas in which a figure stands before some sort of astral void, holding a gas lantern. The curator had just mentioned that the late artist painted the work soon after his father passed. “I don’t tell you this to make it tragic—I tell you so you’ll know the fucking awesome power humans are capable of in the face of loss.”

This show was curated by Molesworth and takes over the majority of David Zwirner’s 19th street hub, boasting over twenty-five paintings by the incredibly prolific Noah Davis, exhibited together for the first time. In addition to his painting practice, Davis also founded and built the Underground Museum (UM), an artist-run exhibition space in South LA’s Arlington Heights neighborhood in 2013. (Though so recent you can almost reach back and touch it, this was still a time in LA when a zip code was everything.) Davis died in 2015 at just 32 years old from a rare form of cancer, two months after the UM nailed down its first, hard-won collaboration with a major institution, LA MOCA, which was helmed at the time by none other than Molesworth.

Context and legacy aside, the paintings are marvelous. Primarily figurative, they’re narratively and emotionally murky yet fiercely charged with heat. Rothko is invoked in Davis’s voids and endless skies, while other art historical figures (Davis was reverent to the spells of art history, having studied at—and dropped out from—Cooper Union) are compulsorily alluded to: Kerry James Marshall in the heroic depiction of housing projects and the urban plight of African Americans, as well as in the paint handling; Giorgio de Chirico in both the shaping and intentional mishaping of perspective and spatial logic; Fairfield Porter and Andrew Wyeth in the figure-ground relationship; the list could go on ad infinitum.

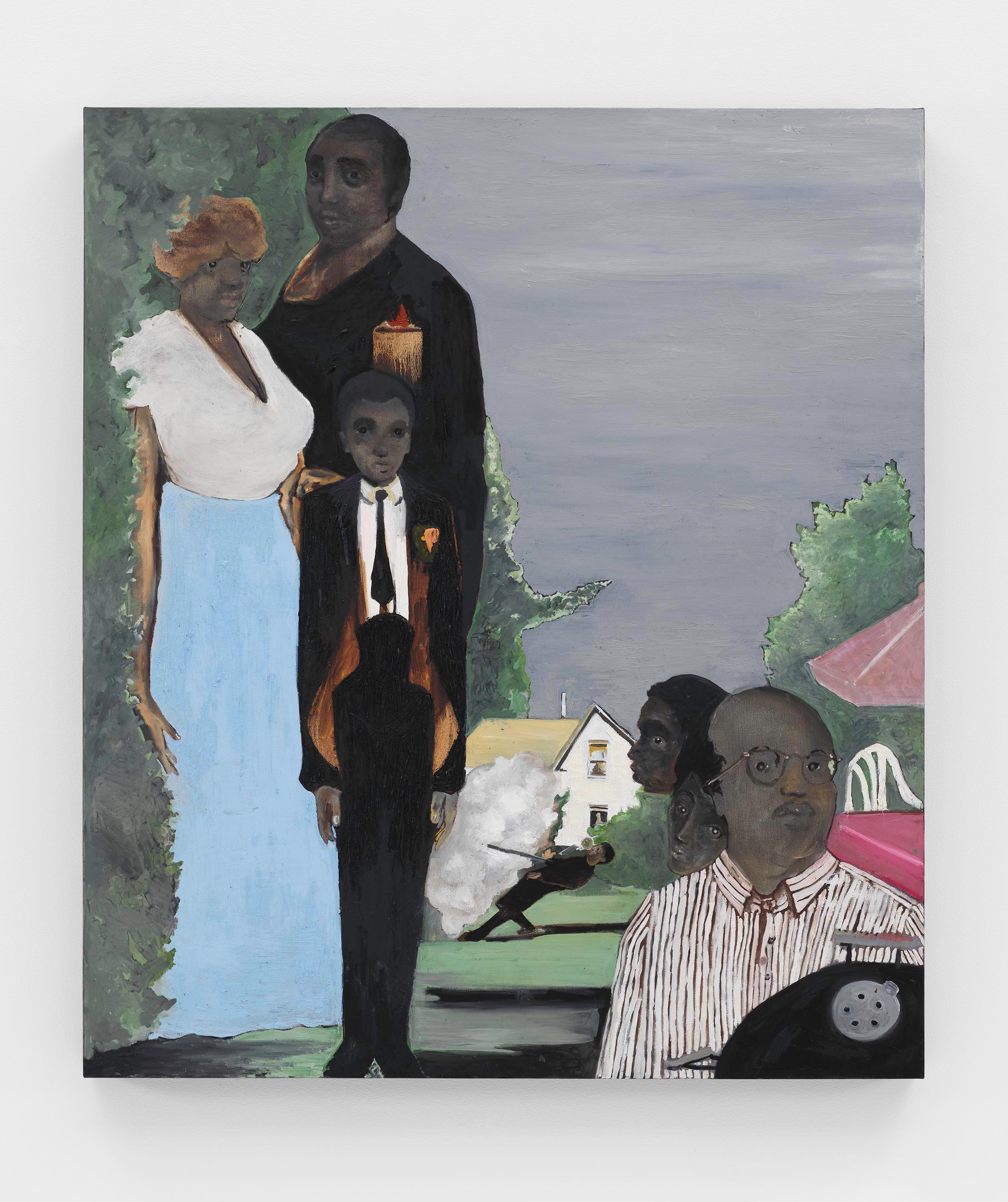

In The Last Barbeque (2008), three figures stand to the left of the canvas, seemingly two parents and their young son, all dressed to the nines. The mother is slightly obscured by hedges and the father and son’s suits seem to be dissolving, or perhaps smoldering. In the lower right, there is a cheap charcoal grill, behind which three more figures float in a manner that breaks dimensional rationality. In the background, a seventh figure is mid-fall in some abstracted moment of violent dynamism. I can’t entirely parse the narrative here, and it’s disquieting in every sense. With the funereal outfits and the title—an allusion, I presume, to Leonardo’s The Last Supper—we read death, we read betrayal. But we also read tenderness, familial tragedies that are so wildly unavoidable, and the countless membranes they form which we must then pass through.

In Pueblo del Rio: Arabesque and Pueblo del Rio: Concerto (both works 2014), the artist paints scenes in the titular Paul Williams-designed South LA housing project. The sky above is a deep, eggplant purple only conjured occasionally through the city’s signature cocktail of smog and sunlight. In Arabesque, a suite of half a dozen ballet dancers perform the eponymous dance step, one leg extended behind them, and in Concerto, a single figure sits before the buildings at the bench of a grand piano.

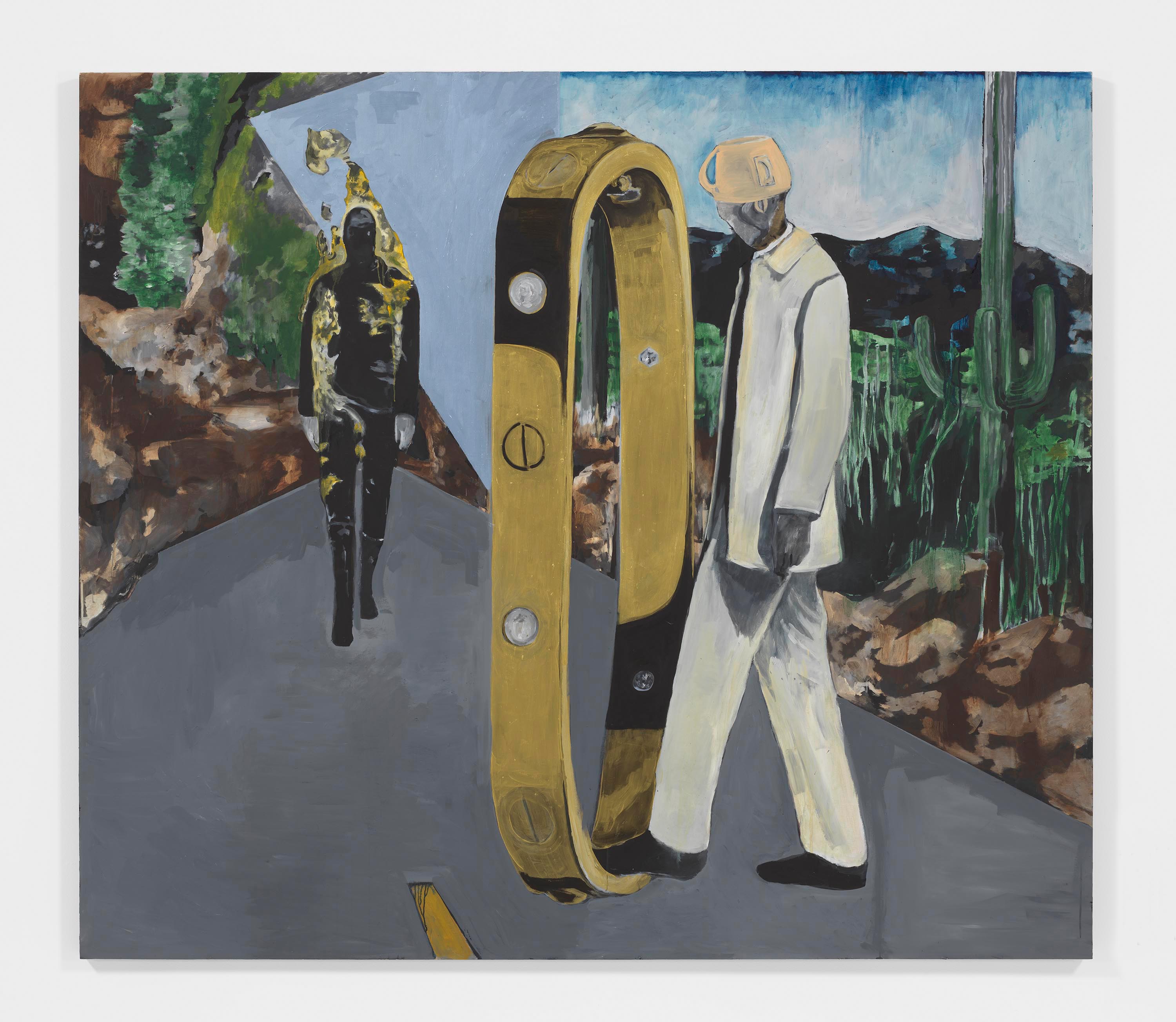

Davis also wasn’t afraid to wade into deeply surreal waters. In Imaginary Enemy (2009), a figure who has what appears to be a large cup on his head, walks through the portal of a massive Cartier bracelet. Or take Prey (2010), perhaps the strangest painting in the show, wherein a female figure bends precariously towards a fawn who looks out at the viewer. These works, when juxtaposed with the domestic paintings like Bad Boy for Life (2007) in which a small boy is spanked by his mother, or Untitled (Moses) (2010) where Davis’s son is shown bathing in a kitchen sink, combine to create a world where the everyday is just as special, and just as heartbreaking, as the preternatural.

Towards the end of the walkthrough with Molesworth, the diffuser on one of the track lights (which no one was near) suddenly fell off. “Oh hi Noah!” Molesworth cried out, followed by, “oh I said I wouldn’t cry today.”