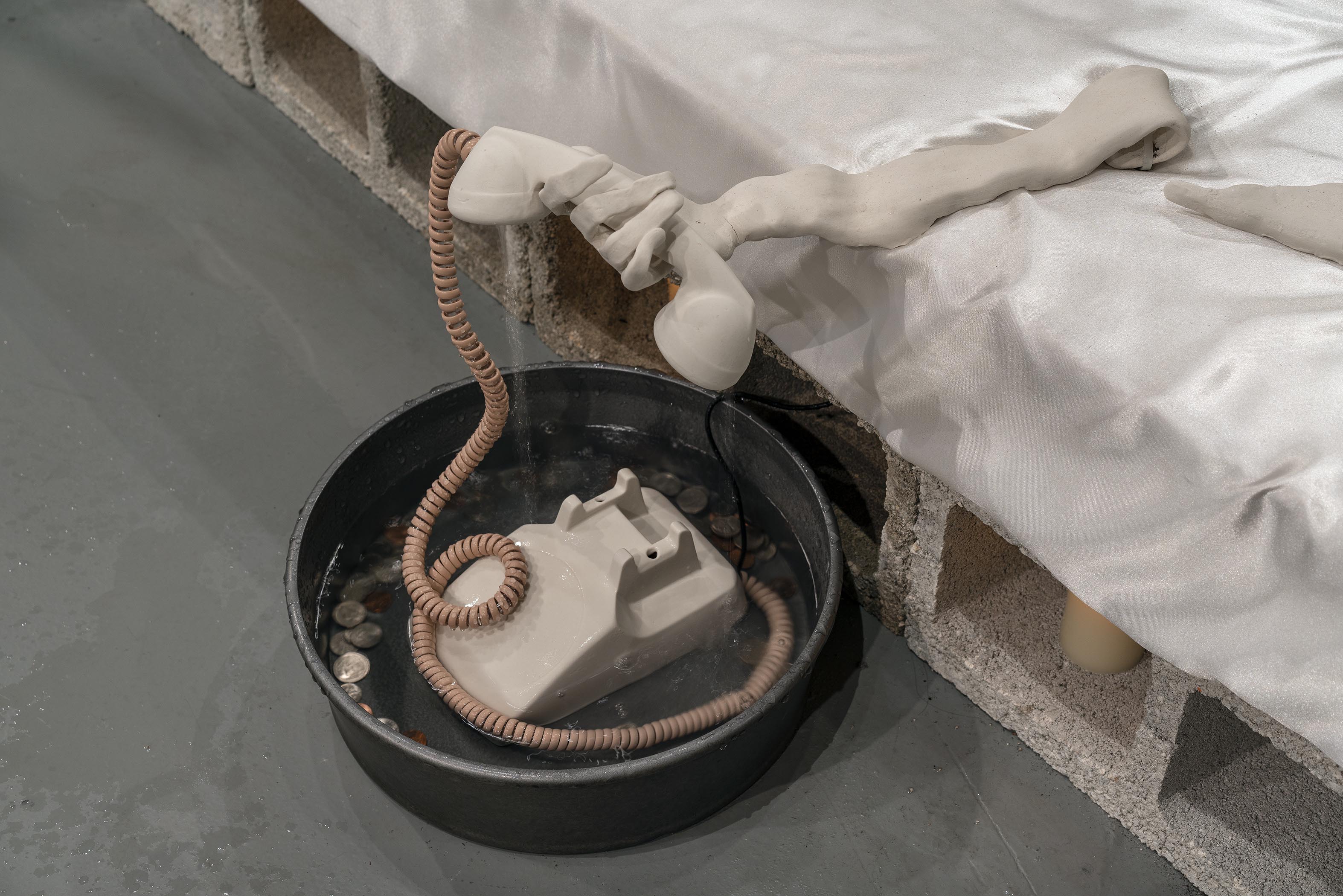

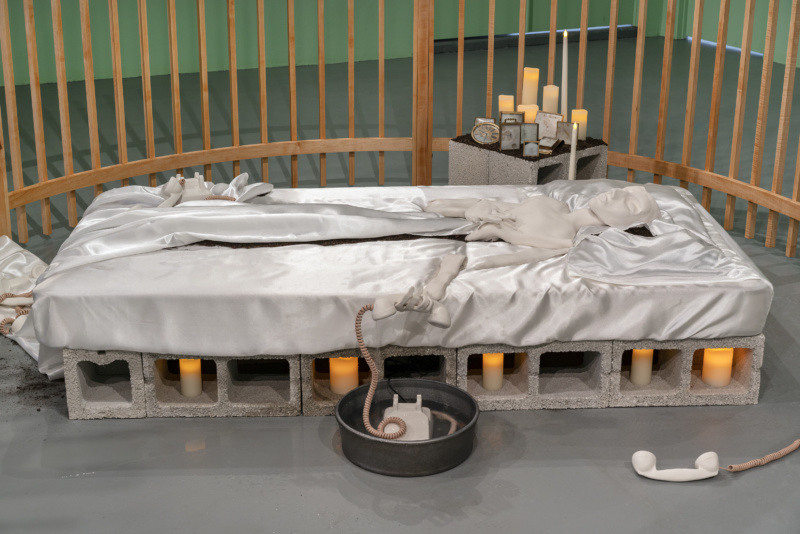

You might not notice the ying-yang shape of Cristine’s Secret Garden, Cristine Brache’s exhibition currently on view at Locust Projects, but it’s there: a slightly S-shaped maple fence—Bending Without Breaking (2019)—that runs along the middle of the gallery, holding, in each curve, two sculptures bedecked with fake candles, cinderblocks at their base. It’s best to take in the show while traversing the fence, as if you were peering through at some private scenery: Statues of women’s faces, saint-like and stoic, laying on a bed—a porcelain phone dripping a puddle below—or staring at themselves in a vanity mirror. Pink-tinted windows. Melting clocks. Rumpled sheets. A door to nowhere.

Orishas, the deities and spirits of Santerías—and other religions of the African diaspora—have often been codified as saints, their trappings disguised as completely Catholic to keep them hidden and safe following religious colonization. There is an orisha for the sea, for iron, for the cemetery, for power; Brache, who is Puerto Rican and Cuban, has created her own spiritual monuments here, for matriarchy and womanhood—the beautification rituals, the quiet pain, all the work that comes with it. We spoke to her about the show (still on view till the end of the month) and its origins.

Tell me about this specific image of Miami front yards—the way they become altars. What is your memory of them like? My grandmother never really had altars in her front yard, but she had a big shrine inside of her house at the end of a long dead-end corridor—it was walled up because she converted half of her house into a duplex. I have a sentimental memory of her making a plaster hand-painted statuette of Yemaya when I was a child. Yemaya is always depicted so elegantly, typically surrounded by waves, her hands open towards you in this very welcoming and caring way. I remember her sitting at the table, employing a similar sense of care as she formed the figure.

My father also had some shrines in my childhood home. He always has a statuette of San Lazaro around, though they’ve grown smaller and smaller in size as time has passed. When I was four or five or so, there was a tall statuette of San Lazaro in the bathroom and it used to scare me every time I went into the bathroom. San Lazaro is an emaciated, sickly figure who looks like he is in a great deal of pain and always has two dogs or wolves at his side. His main attribute is good health. I was born on his day—December 17—and my grandparents wanted to call me Lazara, but my parents opted for a more western first name to help me better assimilate into American culture. I wish they’d done differently.

I never really considered Miami front yards until I was away for a while and returned. Being away allowed me to take note of these front yard altars, or casa de santos. I haven’t really seen them elsewhere in the U.S., which led me to de-normalize them. I recognize them as something special and part of my history. I want to document them because I fear this thing will be erased in some abstract way inside of me. As a first generation immigrant, I see culture getting lost as I grow older, so I want to capture it in order to keep it in some way.

The casa de santos are usually for San Lazaro—Babalú-Ayé—or Santa Barbara—Changó—and I think they abound most in Little Havana and Hialeah. I was born in Hialeah, and later lived in Little Havana in my early twenties. I would drive around photographing them because they are beautiful and they fascinate me. I think as an adult, I realized how precious this characteristic is to Miami, to parts of my family, and also how encoded it is. If you don’t know about Santeria, then you don’t really know what these statues mean or how they’re honored. You’d simply read them as Catholic paraphernalia.

The Orishas are deities of natural and spiritual elements, and deeply human concepts like labor and motherhood. Tell me about your understanding of Santería. I can only understand Santería through my connection with my grandmother, how I’ve seen her practice it, and how she’s included me in such practices. I suppose it’s a very private sort of understanding.

Historically speaking, its syncretization under Spanish colonial rule is the draw for me, and the throughline of my exhibition. Codification is an inherent subversive quality that has protected Santería’s origins in Yoruba traditions. People will always find stealthy ways to continue to express themselves when their constitutions are considered an imposition or at odds with the existing state of affairs. Some constitutions come with cruel consequences as a result, so people adopt survival tactics to preserve their identities, wants, and needs. I find myself drawn to the complexities of structural power dynamics and submissive coping strategies.

Your altars are different; they’re your own. What do they represent? What are they the gods and goddesses of? I thought a lot about the ways in which maternal figures in my life codified their own identities to survive within their specific contexts. I thought about my grandmother’s obsession with appearance and beauty. As a young adult woman of the 1950s, she wasn’t allowed to work or take on hobbies, to develop a sense of self independent of a spouse or children. She was limited to childcare and her appearance, so she channeled all of her self-expression into it. Having this be her method of survival and perhaps a bit dated, she always stressed the importance of a woman’s appearance to me growing up, because she wanted me to survive. So there are two shrines dedicated to her, and those thoughts and feelings.

The center of the installation is a long S-shaped curving maple fence. It is reminiscent of yin and yang, and as my friend Blair wrote, “a spine that bends but doesn’t break.” Within the two arcs are opposing responses to cultural impositions women face that tend to give rise to strength or weakness. On the front end, there is a porcelain figure of a woman, reminiscent of my sister, with an apple on her head, like William Tell’s son. She is surrounded by fainting Oscar statues, Magic 8 balls, and more apples. She is holding the space and the first thing you see when you enter the room. She is brave and doesn’t fold. Her strength is exactly parallel to her vulnerability and she knows it. Any damage done to that foundation may cause it to crumble, like a building. On the opposite end of this arc lies a wraithlike figure on a bed of soil. It is a shrine for mental illness, exhaustion, and paralyzation. Collapse in response to all the inequities that have hurt her: my mother.

I am curious about the candles in the windows; that the windows and doors are pink; that the space feels romantic, sparse. Can you talk to me about the challenges and excitements of building the space? The windows and door, like the fence, and the Miami-green walls are me. I am everything that these women are and are not. Their experiences shape and contain me. I very much wanted the space to feel like an exterior brought into the interior. I chose architectural elements that can be identified as a Miami thing to people who live here. The pinks and the maple are yonic to me. When maple curls, it has this iridescent quality like mother-of-pearl; the pink Lucite reminds me of soft tissues and folds. With the candles, I wanted it to evoke feelings of being at a vigil, or something Catholic and lost time.

Regarding production, I am a very organized and calculated person. I am very good with planning, envisioning something and finding ways to make it real. I love math and problem solving. I also love to use my hands. The woodwork in the exhibition was very exciting for me to make. I dressed the wood myself. Having the opportunity to make larger work has been both exciting and challenging. The whole experience has been very meaningful to me.

There is something immensely private about sharing a space like this. Is there anything healing or cathartic about making these ideas very physical? It is super private for me! Being able to walk my family through the exhibition, having their support in making their experiences heard and seen in this specific way makes me feel accomplished—like I was true to their experiences and created a platform for them. Generally, I find all art making to be cathartic and healing. I enjoy making objects speak.

I am obsessed with the objects in the show. They’re so infused with memory. Resin-filled clocks and 1990s vanity mirrors and wetness. I cherish symbolism a lot, how I identify with objects and their meaning, and how this meaning can be destabilized to create a whole new subset of feeling. I reference obsolete media because it frames a specific period of time. For example, I associate VHS cassettes with my formative years. The porcelain rotary phones also capture a period in my life; they are sort of stuck in time like the resin-filled Swiss and French alarm clocks on the nightstand in the same sculpture. There is a 1990s Clairol True-to-Light vanity mirror that faces the bust inspired by my grandmother, the same one I saw her and my mother use as a child. Both of these objects rest on a stack of analog weight scales, as does the small acrylic tower that is adorned with more porcelain: eggs, a hand mirror, and owl, and a can of the popular 1990s Aquanet hairspray. My grandmother’s vanity looks very similar to this arrangement. She has a lot of owl figurines in her house because they scare away bad spirits.