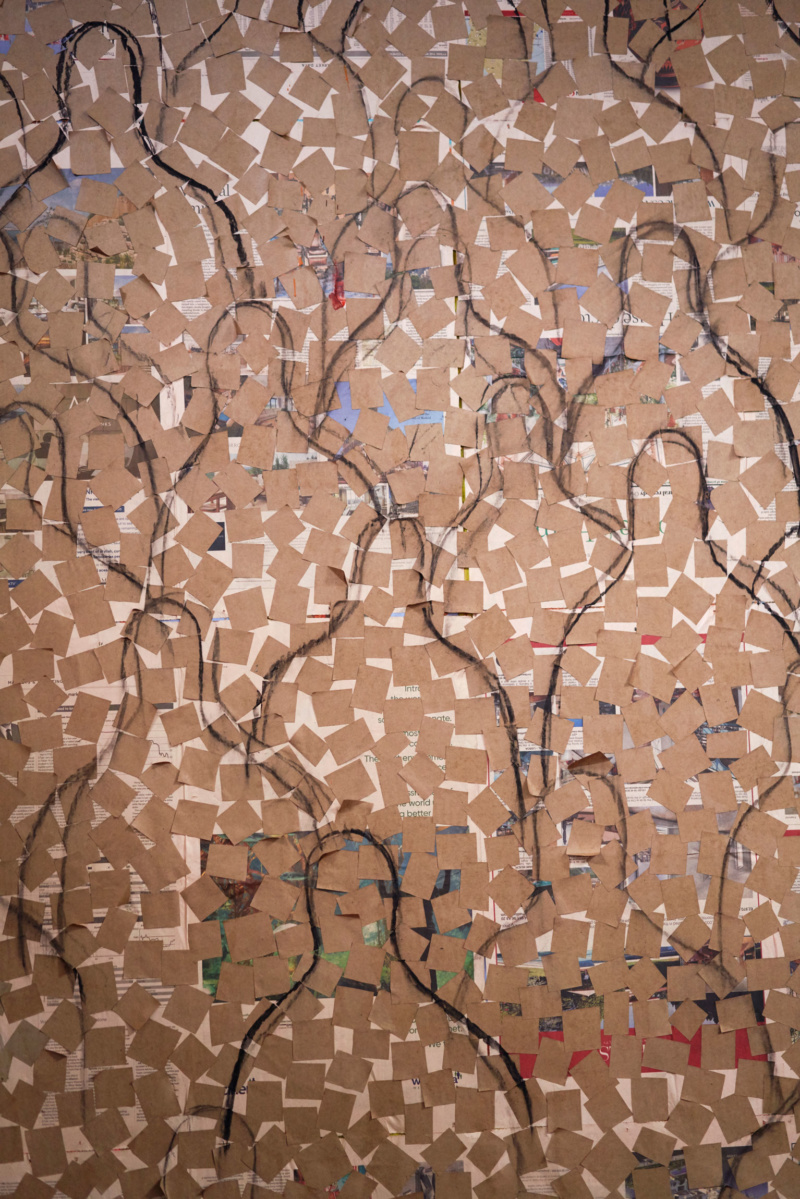

“I use a knife as much as I use a brush, and I use charcoal as much as I use paint,” artist Derek Fordjour explains, gently shuffling through the fragile, heavily textured canvases that line the floor of his temporary Boyle Heights studio. His signature palimpsestic composite portraits reveal layers of shredded newspaper pages and skinned corrugated cardboard between washes of blazing neons and smudges of charcoal. “I never feel that all the labor it takes to get to these surfaces is a waste. You never know how it’s going to work out. There’s some chance in it.” Fordjour’s elevation of these humble, mundane materials is a reference to the hand-me-downs he grew up passing along to relatives in Ghana—clothes that would eventually resurface in family photos—as much as it is to the Global South, a notion that people of color occupy a certain physical and psychological position regardless of geography. “People there tend to use a collage, or gumbo, aesthetic of working with scraps. Putting these torn or broken pieces next to a pristine work or space like a museum feels really honest and democratic.”

Fordjour often expands his undulating surfaces into multidimensional spaces, such as with PARADE, a carnival fantasyland he created within New York’s Sugar Hill Children’s Museum of Art & Storytelling in 2017, complete with popcorn and fresh hay. Alluding to Harlem’s rich history, his installation of eight large-scale mosaics, also titled PARADE, was commissioned by New York City’s MTA for the nearby 145th Street station. Starring a line of majorettes and drummers, the mosaics depict the area’s legacy of African- American parades, beginning with the 1919 celebration of the Harlem Hellfighters—New York’s all-Black World War I regiment—and continuing with the African-American Day Parade, which began during the Civil Rights era and is still active today. Further down Manhattan’s West Side, the Whitney Museum commissioned the mural Half Mast across the street from its main entrance. Installed last fall, the mural shows a vibrantly-hued dense crowd scene and deals with gun violence: police officers, students, targets and civilians all share the same small space, which is occasionally dotted with the buoyant balloons and beloved teddy bears of victims’ makeshift sidewalk memorials.

“JRRNNYS”—Fordjour’s first major solo show in Los Angeles, on view at Night Gallery through March 2—presents STOCKROOM Ezekiel, a site-specific three-sided room that is his most intricate, and perhaps most revealing, work to date. After creating BACKROOM, a shanty-style stockroom inside Josh Lilley Gallery’s booth for Art Basel Miami Beach late last year, and UPPER ROOM at Robert Blumenthal Gallery in 2015, which was based on a prayer room his Ghanaian mother maintained in his childhood home in Memphis, STOCKROOM Ezekiel offers more insight into his conceptual process. “I’m thinking a lot about incarceration and my own experiences with the criminal justice system, and growing up in the ’90s and seeing the crack era, and where we are now with sentencing.” The installation’s name honors the life of Ezekiel Archey, a convict laborer who worked under Alabama’s brutal convict leasing program in the late 19th century.

The installation closes in on you: the 12-foot-high wooden walls hold up grids of a thousand small cubbyholes inside the room, accessed by sweeping through meat-locker-like plastic sheeting curtains. Some of these “cells” are populated with small objects, and some are upholstered with designer fabrics recognizable from the early aughts’ logo-mania days: Gucci Gs and Louis Vuitton’s unmistakable monogram in browns, grays and reds, representing what the artist refers to as “modern material ambition”; others are left in their raw state. Still other articles are made from the unmistakable stiff orange cotton of prison uniforms. Some cells host gleaming Mercedes-Benz hood ornaments; there are a few blue-and-white discs plucked off of BMWs. One cell holds an elegant vintage alarm clock, while others still contain a single—or a few—scuffed-up, precariously stacked billiard balls. Or a dart. Or a baseball.

“There are a few things that are recurring for me, one of which is my interest in games. There’s something of a gaming logic to most of my inquiry.” For STOCKROOM, Fordjour fabricated several hundred hand-sized busts from the same mold in a variety of materials—including resin, copper, dirt and plaster. The small, traditional statue is familiar, if uncanny: “This one references a historical bust and the Tuskegee Airmen,” he explains, a nod to the African-American Air Force pilot group that fought in World War II, the first to do so in the U.S. Armed Forces. “But then again, their leather helmets make them look like sportsmen, or game pieces, too,” he adds. “I’m interested in how our bodies are larger in relation to this figure, and so we feel that they’re expendable. We have lots of autonomy or dominion over them.” They light up intermittently in differing configurations, programmed on an Arduino board. “The whole thing functions as a gaming board, too,” Fordjour explains.

So, is this a system in place here, or is this design given over to chance? “Right…” he laughs.

in your life?

in your life?