Tauba Auerbach has the kind of mind that imposes systematic, scientific thinking onto everything in her path. She can’t help it.

Her big Public Art Fund (PAF) project debuting in New York this summer, Flow Separation, is an elaborately painted 1931 fireboat—every surface of which will get a “dazzle camouflage” pattern, a riff on how World War I ships were once painted to outsmart the enemy’s range finders by confusing them.

The John J. Harvey, as it is officially known, will make trips around New York Harbor (as the retired fireboat has been doing, undazzled, for 18 years) and its hoses will spray, fountain-like, to the delight of everyone, particularly children. It goes on view July 1, running free trips starting July 13 until next spring. A lot of people would be content to leave it at that—a fun summer art project! Bring the kids!

But for Auerbach, the project, commissioned by PAF in conjunction with the British WWI anniversary organization 14-18 Now, is a chance to explore big questions about both painting and physics—two topics of great interest to the Stanford grad. “Flow separation is a word for the fluid-dynamic phenomenon that happens to the flow behind an object that’s either moving in water or around which water is moving,” says Auerbach, seated in her Lower East Side studio.

Now 36, Auerbach is a West Coast native who has been in New York for a decade and who has steadily gained an audience. She was recently part of a two-person exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, with Éliane Radigue, and she will have a show with her New York dealer Paula Cooper Gallery in the fall.

Flow Separation will have an elaborate red-and-white marbleized pattern that took Auerbach some time to devise. It required a large crew to paint the boat, with her help, by hand in a Staten Island shipyard. The boat had a role in evacuating people from Lower Manhattan on 9/11 and it was immortalized in Maira Kalman’s children’s book “Fireboat: The Heroic Adventures of the John J. Harvey.”

“The thing that most interests me, aside from it being beautiful, is that it’s also a very unlikely-looking kind of camouflage,” she says of the historical technique from its wartime days. “It was not so much about hiding as it was about outsmarting the enemy. And I really like that approach to things. It seems relevant again in our highly surveilled time. I don’t think there is any hiding; I think there’s only outsmarting.”

In these interests, Auerbach joins artists like Laura Poitras, Trevor Paglen and others who are thinking about how art can address the surveillance state. A fireboat is a very large canvas indeed—larger than the satellite Paglen will launch this summer, Orbital Reflector, though decidedly earthbound.

But something that sets Auerbach apart from many other artists these days is her interest in the “haptic,” as she puts it—things having do with touch. At a time when many top artists never make a single mark themselves, farming it out to assistants as part of a conceptual framework, Auerbach is a painter who is fully hands-on.

“Right now I’m doing a lot of calligraphy,” she says. “There’s no way I could outsource that.” Auerbach has recently been in residence at Urban Glass in Brooklyn, learning various techniques including her favorite, flameworking. “I think materials store up information that comes through touch,” she says. “It can be very subtle and something that you couldn’t possibly decode and unpack into words, but you feel it and know it when you see it.”

Auerbach grew up in the Bay Area, and after studying visual art at Stanford, she took a job as a sign painter in San Francisco. “I was a really awful student and just couldn’t wait to be done with school,” she says. “I didn’t want anything to do with academia afterwards. And so I became a sign painter and thought that would be my profession.” But it turned out to be an essential first step on her artistic journey. “It really figures into my appreciation for traditional types of craft,” she says.

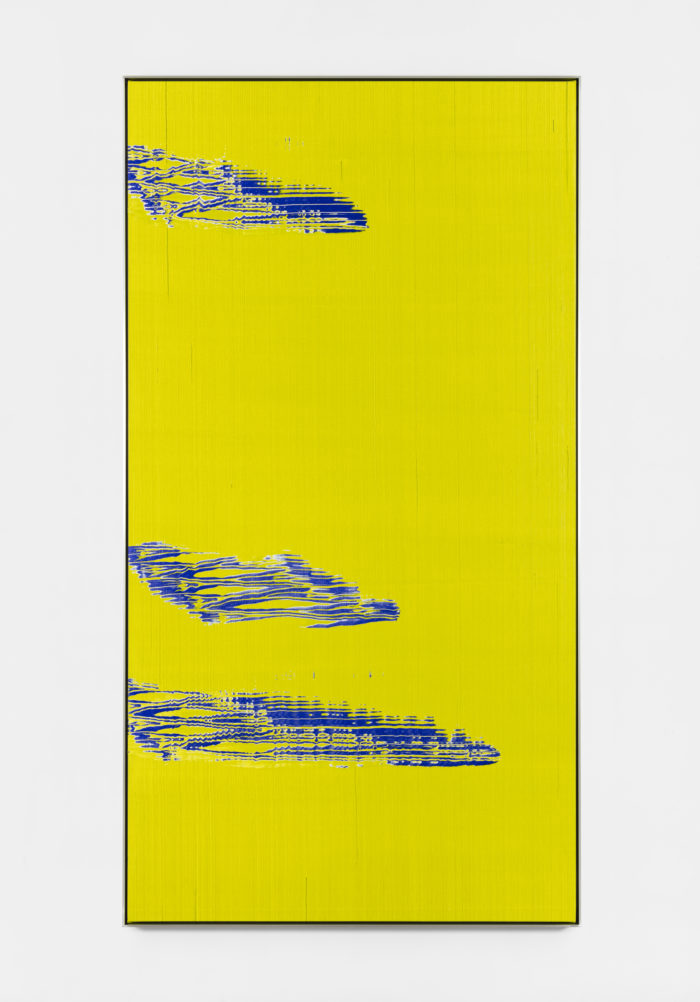

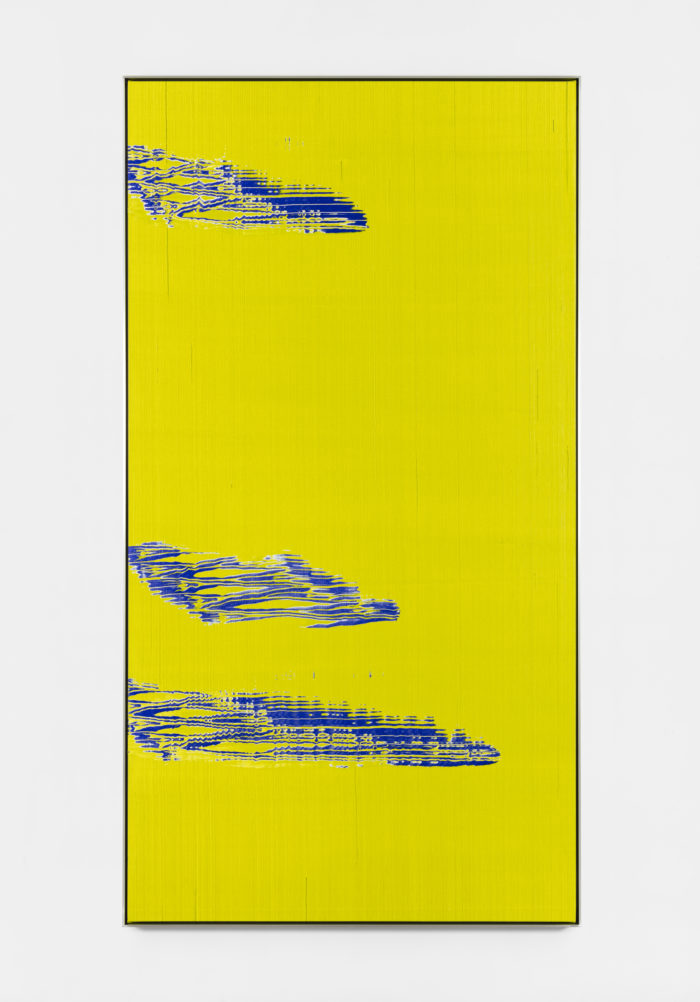

After a couple of years, Auerbach launched herself as a fine artist. Among her early works, her Fold series, which she started in 2009, particularly caught the art world’s attention. To make the works, she crumpled up canvases and sprayed paint on them, creating a complex effect of color and pattern. The series can be seen as part of the recently maligned process painting movement, but it was one of the more subtle and interesting examples.

Auerbach talks about this work from a place of humility—she tried it that way because of a lack of ability on her part. “I couldn’t paint a perfectly creased, crumpled surface,” she says. “So I folded up the canvas.” And she connects that development to the development of the Flow Separation paint job. “I’m not a virtuosic painter,” she says. “And I feel like in order to create something, I have to use a strategy. I say that to myself all the time, ‘Ingenuity over virtuosity.’”

In the case of John J. Harvey, the strategy here was “to keep the identity of the fireboat somewhat intact,” Auerbach says. “Just kind of scramble it, as though a comb was dragged through its original paint job.” In particular, she’s emphasizing that 2018 is the centenary of the Armistice, and that the boat was instrumental to saving lives, not making war.

Flow Separation is a good example of how Auerbach manages in her art to gaze backward and forward at the same time, and the view looks pretty good. She admires the old processes like marbleizing, which directly informed this project. “These were painting technologies,” she says, not always a word used in this context. “The older techniques have principles of physics embedded in them in ways we sometimes overlook.”