For the past decade or so, Alex Olson has been making impeccably refined paintings in which all is never quite as it seems. They pose a number of unanswerable questions: Where does illusion shade into veracity? Is skill simply a way for artists to lie more convincingly? What the hell is truth anyway? As she prepares for her first solo exhibition with Altman Siegel, opening March 9 in the San Francisco gallery’s spacious new Dogpatch space, she tells me how her paintings derive from her studies of neurological perception.

The 38-year-old artist, whose fair complexion and tall stature attest to her Swedish heritage, grew up in Manchester-by-the-Sea, Massachusetts. Her father was an architect and her mother an editor. She studied sociology at Harvard before moving to Los Angeles in 2005 for an M.F.A at the California Institute of the Arts. Her academic background is reflected in the cerebral terms in which she talks about her work. “I’m weaving together a desire for meaning in terms of how the eye and brain look for patterns and meaning,” she says. “And how we differentiate types of information into truths and falsehoods.”

If that makes them sound like chilly optical experiments with their viewers cast as the unfortunate lab rats, then think again. I, for one, submit myself happily to her sumptuously beautiful paintings’ visual manipulations. To look at Olson’s work is to let yourself be taken on a journey of bewilderment and surprise.

Though Olson’s heroes include Robert Ryman and Agnes Martin, she also admits to being inspired by the concepts of Op Art and Surrealism, if not always by their results. But recently, she tells me, she has been increasingly influenced by broader cultural sources: the writings of Maggie Nelson, for example, or Andrzej Żuławski’s 1981 cult horror film Possession.

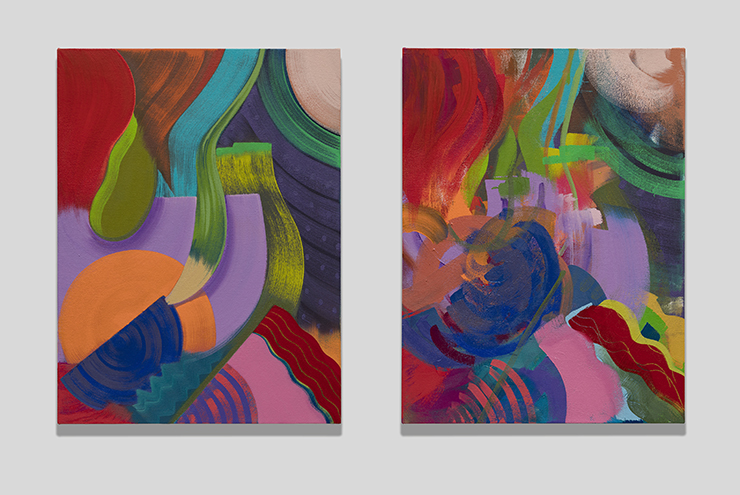

In her airy Glassell Park studio she is currently working on new additions to her series of ‘blind paintings’ begun around four years ago, some of which will be included in the Altman Siegel show. In the latest diptychs, Olson paints one abstract canvas choosing both her brushes and her colors ‘blindly.’ This process, she says, helps her “bypass preconceived ideas of what the painting should look like in order to create something unexpected.”

In tandem with the first blind painting, she makes a second, this time completely blind (with her eyes closed while she applies the paint) relying only on what she calls her “mind’s eye.” While Olson’s work has long distinguished itself through its crisp neatness, these blind paintings are notable for being, well, a little scruffy. The ‘blind paintings’ are a humorous critique of the ideas of truthfulness and authenticity that are historically attached to the artist’s gesture. Throughout her work, she balances witticisms with sincerity, theoretical analysis with visual pleasure. “People are complex,” she says. “How they take in information is complex, and I hope the paintings are as well.”

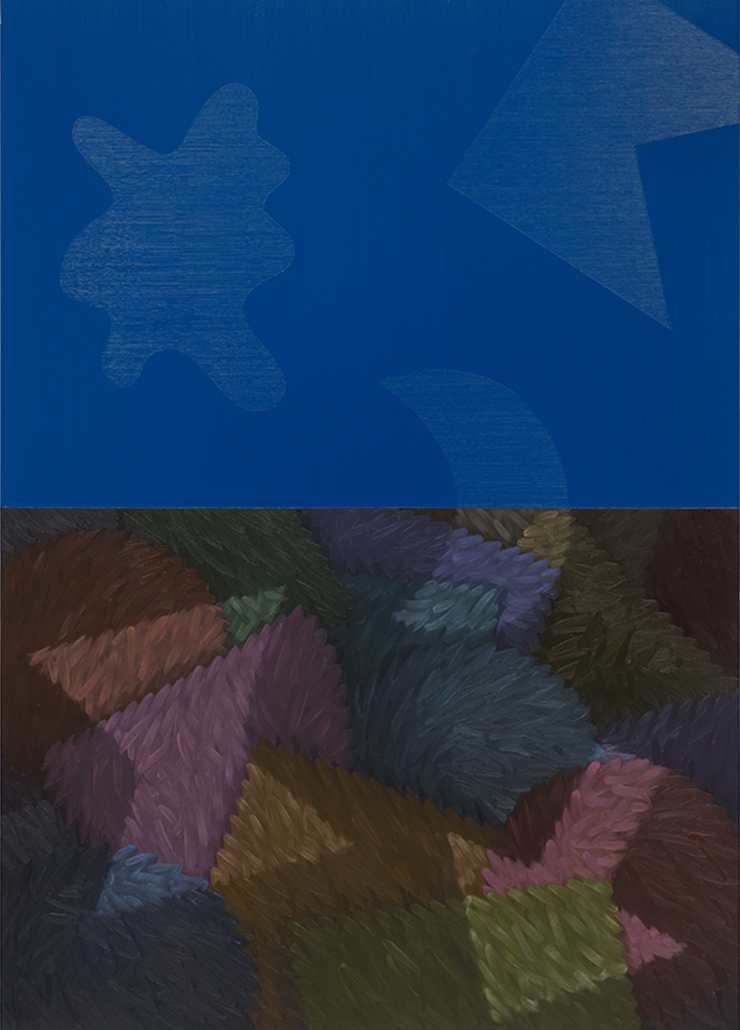

As such, Olson can always be relied on to throw a monkey wrench the most smoothly running engines. In other new abstract works, she has introduced the unexpected motif of a sailing boat. She tells me that the move was inspired by a story told by her mother, who worked as a children’s book editor. One illustrator developed what he called the “blue boat theory” in which he would add an incongruous blue boat to his picture, intending that the editors would remove it and thus leave the rest of his work intact. Olson says that the boat was her answer to the question of “what a visual speed bump might look like” or “a swerve in the viewing experience.” By doing so, she transforms abstractions into seascapes, while the little boat symbolizes what Olson calls her “search,” a search in which she invites her viewers along for the ride.

in your life?

in your life?