We live in a time of masks, not the least of which is our own public persona. We put on our face, we Snap and ’gram, we influence and brand manage. All the while, our masks stay neatly in place. I’m not disparaging masks. At times, they are necessary—should we take them off, we would be writhing masses of emotion.At night, when Kierkegaard suggests we take them off, I posit that some masks stay in place and remain a part of us. With very different methods of execution, sisters Alex and Vanessa Prager both dissect people intensely in their work. Looking is not necessarily a form of unmasking, but seeing is. And in this dissection, both Prager sisters allow us to see their subjects, to consider the people behind the masks.

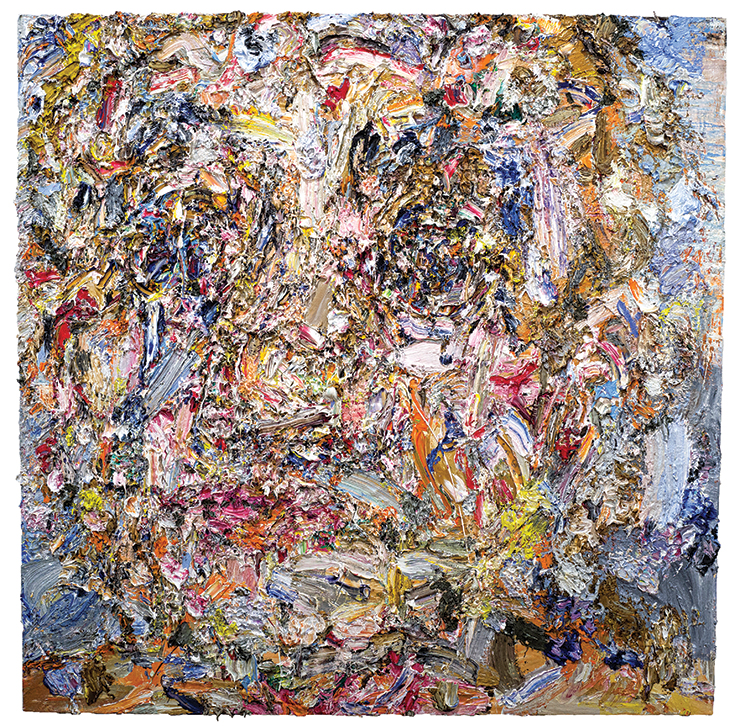

Vanessa Prager’s paintings are large portraits—she enjoys working on eight-foot canvases these days—done in what she describes as a cross between Pointillism and Maximalism. This translates to tortured souls rendered with thousands of thick richly colored marks, a nearly 3D, ultra-impasto style that places her in a historical lineage after Frank Auerbach or Willem de Kooning. Vanessa told me her subjects aren’t particular people in her life but amalgamations, the marks acting as surrogates for their emotional baggage.

“I just want the subjects to be raw, naked,” says Vanessa. “Don’t tell me how your day is. That’s what all the color and texture is. My cat threw up this morning, I bought a nice Mercedes, my house is great, I have four ex-husbands. But behind all that there’s just a chill dude who doesn’t maybe need to talk today. And that’s okay, too.”

She is sitting in a cushion-filled romper room in her Downtown Los Angeles Arts District apartment. Plush animals from the film The Secret Life of Pets are on the cushions. In the film, as soon as pet owners shut the door, the dogs, cats and other house animals take off the mask of pet-dom and start talking, listening to heavy metal and playing video games.

“I definitely think there’s a similar string that we’re both following in our work, which is the mask that people wear, the façade that can be ugly or haunting, and who the person is beneath it,” says Alex when I interview her earlier in the day on the same cushions. “Her work has gotten a lot stronger with the paint getting messier and more sculptural.”

Alex, 37, is five years older than Vanessa, and her oeuvre has reached a very wide audience with works that are no less anxiety-filled. She has shown her photographs (lush, hyperreal scenes that have been compared favorably to Gregory Crewdson and Philip-Lorca diCorcia) and Lynchian short films (which star Hollywood actors like Bryce Dallas Howard and Elizabeth Banks) at venues such as the Saint Louis Art Museum, the Goss-Michael Foundation in Dallas and Galerie des Galeries in Paris.

The most recent was filmed in collaboration with the Paris Ópera Ballet, and is full of a terrifying anxiety about audiences, a line Alex has been following since her Face in the Crowd series. When Benjamin Millepied, the then-director, invited her to do the film as part of his initiative to work with artists at the Ballet, it took Prager “like an hour” to come up with the concept. In the film, La Grande Sortie, a prima ballerina played by real-life étoile Émilie Cozette makes a mistake-riddled comeback in front of an unforgiving audience, set to the score of an eerie adaptation of a Stravinsky composition by Radiohead’s Nigel Godrich.

Following the premiere of the film in Paris, Alex screened it as part of her exhibition at Lehmann Maupin in New York. The film was accompanied by a companion series of photographs taken during the film shoot and a dance performance at the gallery. While preparing the performance, Alex struck up a conversation with several of the dancers, who confirmed her interest in the dark side of the ballet world.

“One of them was talking about when you first start, you’re just a kid, but you have a favorite role that you want to play,” Alex explains. “There is an amount of disappointment that gets attached to that role, because, for example, it’s not given to you. Ten years later, you might get to dance that part, but you can’t even enjoy it because you’ve gone through so much anxiety related to it. But all of this is happening within this façade of beauty and perfection, and everything is grand. It’s a very interesting world. It’s not all that, but that’s the part of it that fascinates me.”

It’s a façade that, while being extra conspicuous in ballet, can be easily transposed on the art world. One of the great memes of 2016 shows a dog sitting in a burning house. “This is fine,” says the dog. All around us, things are burning down. There is disappointment and anxiety at every turn, and yet we put on our masks and pretend everything is fine. Which is to say, the Prager sisters aren’t necessarily looking to be optimistic about the world.

“We’re both interested in the not-happiest side of life,” Vanessa, who often collaborates on Alex’s films as an actor, tells me. “Not because we’re not happy, but because that’s part of life, and it’s valuable too. In modern society, it is frowned upon to not be happy.”

In her 2015 “Dreamers” show at Richard Heller in L.A. and “Voyeur” at The Hole in New York earlier this year, Vanessa’s work shifted from a sort of critique on the nature of masking to an acceptance—“I found empathy,” she says—for the need to cover up.

“When I started with ‘Dreamers,’ I was like, Everything is fucked,” she says. “In ‘Voyeur,’ it was, no, actually most people are really cool, there’s just a lot of drama poured on top. It was less cynical and just a deeper view of me actually studying these characters in people.”

And so Vanessa—with her gobs of paint that mimic the make-up one might cake on to hide a blemish, and Alex, with her photographs and films that linger with an apprehensive artifice—create work that tries to pry away the perfection. There are a lot of differences in their art, fundamental differences where it’s actually very rare for them to even talk to each other about their own work, but when you boil it down, the results from both are unsettling, unnerving and ultimately terrifying, even as they try to find common ground with the faces they’re focusing on.

“There are horror elements in my work, in the same way that there are horror elements to life, but there are a lot of other layers to it, as well,” says Alex. Vanessa may well have said so, too.

in your life?

in your life?