“I want my art to be like breakup music.” This is where artist Spencer Lewis and Orange County Museum of Art CEO and Director Heidi Zuckerman began a recent conversation for CULTURED. Funnily enough, it’s also how they began their respective forays into the art world as teenagers. Lewis was riding low from a split and found solace in kicking around found materials, while Zuckerman, feeling the same depth of emotion, wandered into a museum and found herself transported. Art, like music, was a way for the budding creatives to transcend their current circumstances.

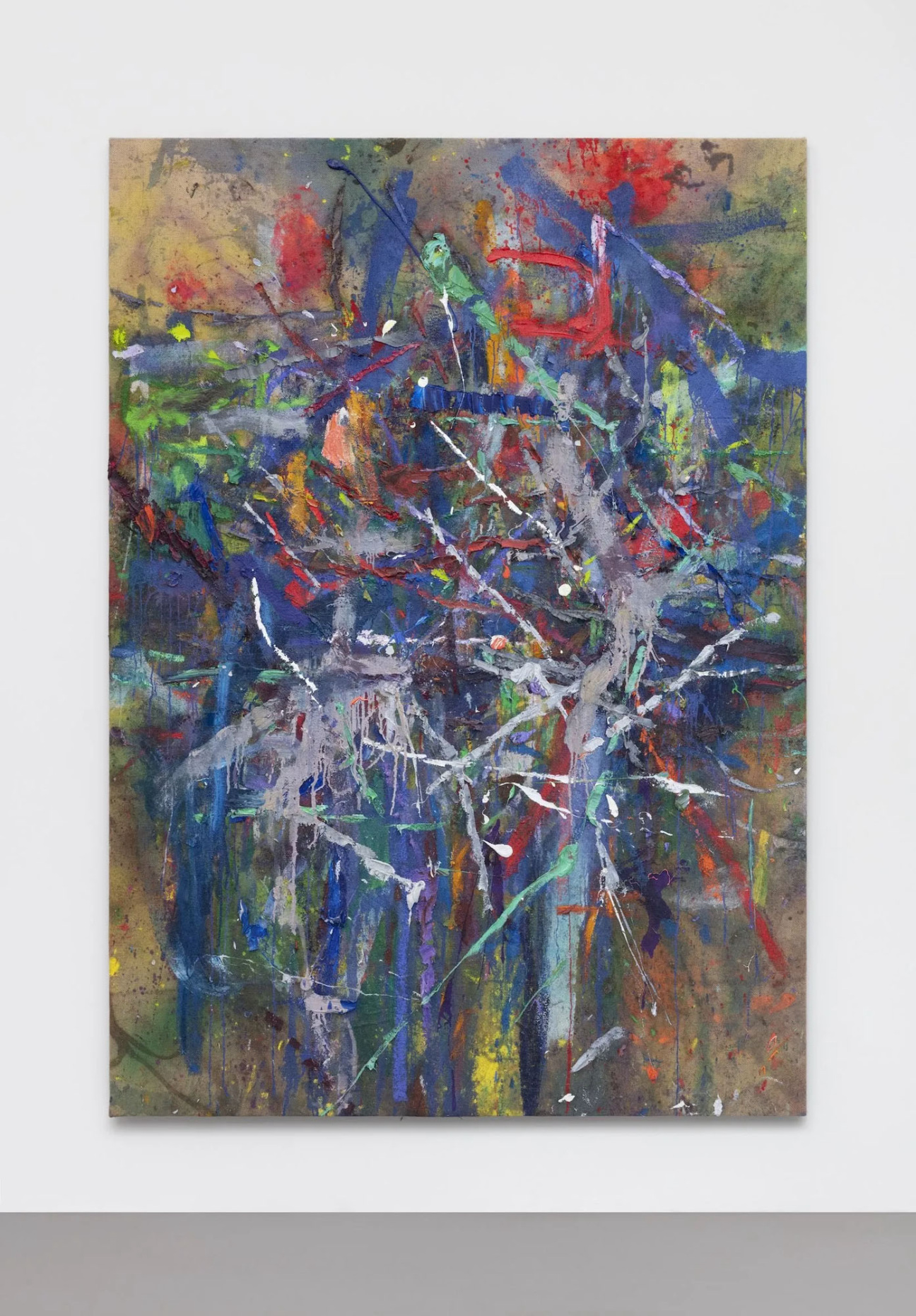

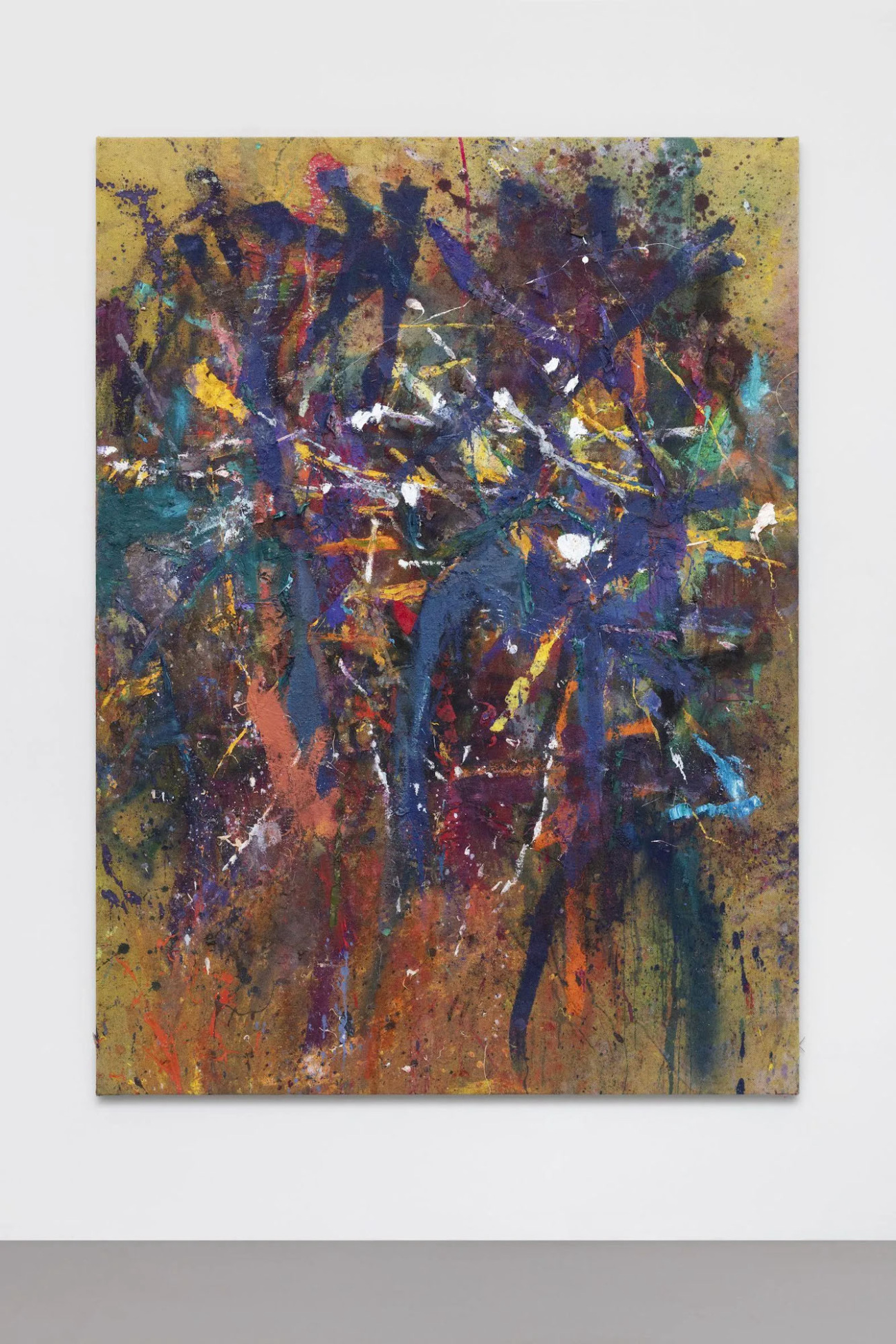

Today, Lewis’s abstract paintings burst off of his cardboard and jute canvases. Even all these years later, they still carry an intensity suited to the emotional volatility of heartbreak. Amidst the chaos, however, Zuckerman sees moments of calm and reprieve in his work, which has been exhibited globally and sits in the permanent collections of DC’s National Museum of African American History and Culture at the Smithsonian Institution and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas.

Zuckerman, who cut her teeth at New York’s Jewish Museum and the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, came to OCMA after a stint as director at the Aspen Art Museum, where she oversaw a period of exponential growth. Within a year at her new post in California, she led the opening of a new building, which drew 10,000 visitors in its first day.

This month, Lewis’s initiative Arts.Giving is set to release a series of his works on paper to support a plethora of charitable organizations. This will be followed by two solo exhibitions opening in 2025: a January showing at MASSIMODECARLO’s Pièce Unique space in Paris and his institutional solo debut at La Nave Salinas Foundation in Ibiza.

Ahead of this cornerstone year—and the opening of OCMA’s latest exhibition, “Ordinary Extraordinary,” later this month—Zuckerman checks in with the artist to catalog his journey thus far.

Heidi Zuckerman: I wanted to start off by talking about materials. I wanted to first acknowledge your use of cardboard and burlap in a lot of your works, and the kinds of texture that comes through in your paintings. A lot of vibrancy and electricity comes from that sort of grounding and I'm curious about your relationship to these materials. How did they make their way into your work?

Spencer Lewis: There's a few angles. Obviously, I've been painting since I was young. I started painting oils when I was like 16. My mom was a part-time artist and worked for an interior design firm in the ’80s. I would draw on the white board at work, and I'd work on tracing paper because this is when they first had CAD programs. My mom taught me this kind of direct creativity, maybe even craftiness, too.

Now that I'm thinking about it, I always wanted to be an artist, I guess. But I really got into painting when I had a big breakup with a girlfriend. I was 15, she went to college and I got really depressed. But I had also seen the movie Basquiat. So I was dragging stuff off the street, riding my bike around town, and finding palettes to paint on. I was really inspired by the objectivity of things. I also started doing a little graffiti, although my dad caught me and made me paint over it.

Some of my first installations in college came from going out in a yard and painting a stub or a rock and then drawing lines between them. And then for years, I worked for Mark Grotjahn. Because I was priming cardboards for him, I developed this series called the “Cage Paintings,” which is essentially just how you prime a cardboard. The move to burlap was just a way to formalize that in some ways.

Zuckerman: It's so interesting, your reference to the breakup and where it sent you. I actually have an iconic story myself in a similar moment. I was a little bit older, maybe a sophomore in college. I remember walking downtown in Philadelphia and going into a gallery and being transported from that moment. I realized that art had that ability to take you out of the here and now.

Lewis: I agree, it's so powerful. I was listening to Guns and Roses and thinking about how so much of their music is all about breakups and love. It can be so conceptual and smart and powerful. When you're young, you want that power. I want my art to be like breakup music. I've heard that, when making a love song, you're supposed to sing about God. That intense feeling is something that's so important.

Zuckerman: I was just reading something about the science of listening to music and how it releases endorphins and changes your psychological state. It feels like it keeps you company, and so to have that in a painting is really interesting. In your work I find this sort of oscillation between moments of chaos and moments of calm.

Lewis: It goes right back to the breakup. When I was young, it was purely emotional, right? And then I went to art school and learned a more academic approach. The studio is such a special, emotional place; I work through a lot of feelings there. When I started working again after my mom died in 2013, I was getting really rough with the cardboards. That's when they really started.

I'm interested in what you're saying about the calmness, because for me there’s always a moment where there's stillness in the studio and observation. You're creating and looking, and that for me would be the oscillation. But within a piece, we're talking about language. It's like we are encapsulating moments. We are constructing things. We're dealing with aesthetics. Otherwise, my work could just all be a modernist mess. I want to make work like Koons or something. I really love work like that, but that just isn't how I am.

Zuckerman: I'm gonna call it like the “absence of abandon.” There is always intention to what you're doing. I'm curious about your studio and how it's organized and maybe what a typical day looks like for you. Do you seek those moments of silence?

Lewis: I don't feel like I control so many things. My intentionality has really been about observing the things that I do. It's okay to set up systems, it's okay not to set up systems. It's okay to try really hard, it's okay to not try really hard. Some of that manifests as just casual kicking of paint cans around or doing a splatter. I tried to take last year off, which means being with family, working on life. So many of us artists are completely obsessive and finding that balance is part of that.

Zuckerman: Do you think about abstraction in your work and its place in the history of art?

Lewis: I do. I’ve always been sensitive about labels like Abstract Expressionism because I’m more interested in imagery. I think of my paintings as language, parts and wholes. It's like reading a visual language. My work is always somewhere between abstraction and figuration. I don’t want to fall into aesthetic clichés.

Zuckerman: I love the idea of a painting being like an utterance—a part of a larger, open-ended dialogue.

Lewis: That’s exactly it. My paintings are like parts of speech. They come together like language.

Zuckerman: How do you start a painting? Do you begin with a sketch?

Lewis: Sometimes, but the key is just getting paint on the canvas. The most important thing is starting. I do a lot of digital studies now, but I’m always looking for that moment when things begin to flow.

Zuckerman: It’s that uncertainty before you start, right? The balance between needing certainty to feel safe but also needing variety to keep things exciting.

Lewis: Yes, exactly. It’s controlled chaos, and you need a safe space to step into that. But it’s all about finding a rhythm that works for you.

Zuckerman: What are some things that help you get into that creative space?

Lewis: Lately, I’ve been focused on inspiration: watching a movie in the middle of the day, walking in a park. Those moments can be incredibly inspiring. When I can’t work, like when I’m traveling, that’s when I often have the space to think more deeply.

Zuckerman: It's interesting how travel can shift your mindset and give you a new perspective.

Lewis: Definitely. Showing work in different spaces and languages can be exciting. The translation of ideas across cultures is fascinating.

Zuckerman: It really highlights what matters—what connects people, what we understand, and the beauty of those moments of unexpected connection.

Lewis: I think of it as engaging with data, but in a human, emotional way. That’s why I love the slippage between languages and ideas.

Zuckerman: It’s a perfect way to end this conversation—the idea of “I am” and the infinite possibility of it.