Agustina Woodgate has a massive art practice, fueled by an impassioned, electrically-charged curiosity. The Argentine-born, Miami-based multidisciplinary artist has snuck poetry onto clothing tags at thrift stores, plastered local writers’ poems onto broken concrete sidewalks for O, Miami Poetry Festival; when she speaks, in so many layers, she’s a poet herself. She’s de-stuffed and and re-sewn teddy bears into biomorphic rugs: bright, butterfly-shaped reconsiderations of our detritus. She sands down maps and money, their prescribed meanings, till they’re dust. She rigs clocks to erase their own numbers; time as engineered by “master clocks,” she explains, was a methodology of control for labor practices, and often racialized. With her online radio station, RadioEE, she and her team transmit stories from boats, bicycles, deserts, the edges of politicized borders. Woodgate researches and digs; then researches some more, sharing everything excitedly. She considers, then reconsiders, everything.

Her work, then, comes less from creating, and more from deconstruction—from discovery and inquisitiveness, from communication. She often thinks about territories, their politics and boundaries, how they might be physical or imagined: the arbitrary borders drawn by hegemonic systems of power; the constructs we take for granted as gospel, till we remember they’re wholly manmade (like time, again). Woodgate is among the 70 artists and 5 collectives selected for the 2019 Whitney Biennial, curated by Rujeko Hockley and Jane Panetta and on view from May 17 through September 22. Ahead of the show, we spoke to her (she’s currently studying in Amsterdam) about El Silbo Gomero—a whistled language—time, and her ongoing research.

Agustina, what are you currently working on? Where are you? When your email landed in my inbox, I was in La Gomera, one of Spain’s Canary Islands. I went on a vacation trip that very quickly became a research one, research into an amazing language: El Silbo Gomero. El Silbo Gomero is a whistled register of Spanish used by inhabitants of La Gomera in the Canary Islands to communicate across the deep ravines and narrow valleys that radiate through the island. It enables messages to be exchanged over a distance of up to 5 kilometers.

Due to this loud nature, Silbo Gomero is generally used in circumstances of public communication. Messages conveyed could range from event invitations to public information advisories. A speaker of Silbo Gomero is sometimes referred to in Spanish as a silbador, a whistler. Silbo Gomero is a transposition of Spanish from speech to whistling. This oral, phoneme-whistled substitution emulates Spanish phonology through a reduced set of whistled phonemes. It was declared as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO in 2009.

In the late 1990s, language revitalization efforts began and initiatives from within the community started. By 1999, the revitalization of Silbo Gomero was furthered by education policies and other legislative measures. It now has official protection as an example of intangible cultural heritage. I had the chance to go into a public school to experience one of these classes. It was mind-blowing!

What else have you been studying? How has it impacted your practice? I was so excited listening to you talk about Amsterdam last time you were in town. In the next few months I will be completing a Master’s degree in Design at Sandberg Instituut in Amsterdam, an incredible university that models and experiments with ways of distributing and sharing knowledge and proposes a different kind of pedagogy. There I have been busy shaping PUB, a trans-department publishing platform at Sandberg, the first one in the school’s history. Over two years, together with other students, we have been experimenting with different kinds of publishing methods and distribution. This has been an amazing collaborative experience with incredibly talented beings.

In my Amsterdam studio brain, I am working on a series of projects that will reflect on the last two years of intensive research on the electromagnetic spectrum and network topologies. Everything is very much in process and being shaped at the moment.

When and how did you come into your practice, from the very beginning? I am wondering if you made art as a child, or conducted intense research? When I was a kid, I spent weekends illustrating comic books and building experiments with my brother. I was also an avid collector of crap and nonsense things, like the cigarette boxes of different brands, erasers with different shapes, stickers, letter papers, bottle caps, stones, coins. The long drawing sessions continue until today. I think I developed my style when I was a teenager. I would illustrate our weekend adventures and then photocopy them to gift them to my friends. I then went onto drawing my dreams—books and books of delirious nonsense images.

Your work, especially with your radio station, engenders conversations and connection. I am curious if this is one of the purposes of your work—to get everyone, not just people in the art world, thinking more deeply about the systems around us. Change starts on the ground, right? For sure. This is so well said. I think of art as a tool for communication and a way to expose things from different angles.

Something prevalent in your work is deconstruction: either through conversations, literally erasing or sanding objects, etc. Can you tell me more about this? Thermodynamic laws regulate my process. I use deconstruction and displacement as a methodology for thinking and making. I recombine, activate and repurpose available resources, while setting alternative systems in motion. My work comes about through a logical process of discovery, rather than invention, utilizing displacement as a strategy. My approach is speculative, practical, and site-and-context-responsive, presenting critical possibilities to concepts on social orders, resource management and information distribution—bringing clarity, scale, accessibility.

Tell me about your project with O, Miami Poetry Festival: Concrete Poetry. I am still working on Concrete Poetry, a sidewalk design for Miami-Dade County. Concrete Poetry is a permanent urban design intervention in collaboration with O, Miami. Its first iteration was installed over the summer of 2018 and will continue to expand to other broken sidewalks across the county as they get repaired. Concrete poetry, in this context, is a publishing tactic applied to sidewalks, written by the residents of the neighborhoods where they are placed.

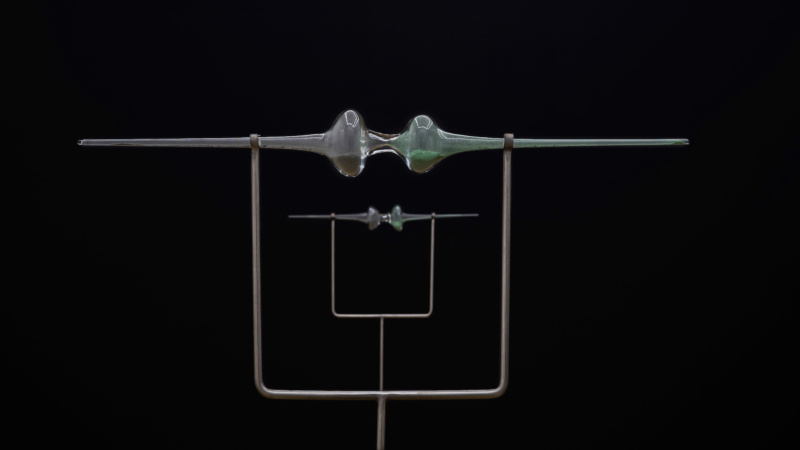

In a statement, Rujeko Hockley said this year’s Whitney Biennial will focus on “the mining of history in order to reimagine the present or future.” Tell me about this vision, how your work factors into this. You are always confronting the awful realities by which we live. Time. Money. At the Whitney, I will be exhibiting “National Times,” an installation exposing timekeeping as labor and value. National Times is composed of 40 analog “slave” clocks operated and synchronized by a digital “master” clock that has unidirectional control over the slave network. The master clock is equipped with a GPS antenna connected to the NIST—the National Institute of Standards and Technology—satellite time base, which uses power-line frequency to keep accurate time.

Repurposed from an elementary school, the master/slave clocks are a hallmark of a factory education system designed for mass orchestration and industrial exploitation. As “National Times” progresses, the minute hands of the slave clocks scrape away the numerals on their faces. The visible grid that connects the slave clocks to the master runs on energy supplied by the local electric utility provider. The clocks will operate until all numbers are completely eliminated.

“National Times” extends my investigations of the ways in which infrastructural politics and poetics organize the politics of public and private space. Previously, I hand-sanded banknotes, globes and maps; “National Times” automates this process of erasure. The contemporary equation of time and money generates a condition of precarious production that never accounts for the real costs of its power infrastructure. ”National Times” depicts current economic measures of labor and value in a process of disintegration , and exhibits a communication network that rules and regulates our daily life rhythm.

A note from Agustina: In December 2017, the Internet Systems Consortium chose to allow the words “primary” and “secondary” as a substitute for master/slave terminology in their DNS server software BIND. Years later, in 2003, the County of Los Angeles in California asked that manufacturers stop using “master” and “slave” terminology for their products, “based on the cultural diversity and sensitivity of Los Angeles County.” The request was met with outcry. In 2004, the Global Language Monitor deemed the term “master/slave” the most politically incorrect term of that year.

in your life?

in your life?