To surprise with Warhol is no easy task. In the words of Whitney Museum director Adam Weinberg at Tuesday’s opening, it’s hard to find someone in the country who doesn’t know Andy. Undoubtedly, every museum-goer arrives with preconceptions about the legendary oeuvre, if not the artist’s quote presaging social media, that in the future everyone can be famous for fifteen minutes. Yet this is the central challenge of Andy Warhol— A to B and Back Again, the Whitney’s centerpiece fall exhibition, and one of the most hyped curatorial endeavors of the decade. Despite Warhol’s ubiquity, the Whitney retrospective, which opens to the public next week, is the first by a major US museum since 1989 (the last, a MOMA survey two years after Warhol’s death at 58). Per Weinberg’s essay in the show’s mammoth, gold-leaf catalogue, this is one of the most complex undertakings in Whitney history.

Indeed, Andy Warhol— A to B and Back Again is monumental and painstaking, with over 300 works, drawn from over 100 lenders around the world— museums, private collections, foundations. Spanning Warhol’s prolific career, the Whitney aims to do nothing less than re-solidify an American icon. According to Weinberg, it is meant to be as relevant a primer for someone who only knows the Campbell’s soup cans, as to the art historian who hails Warhol as the democratizing force in the canon.

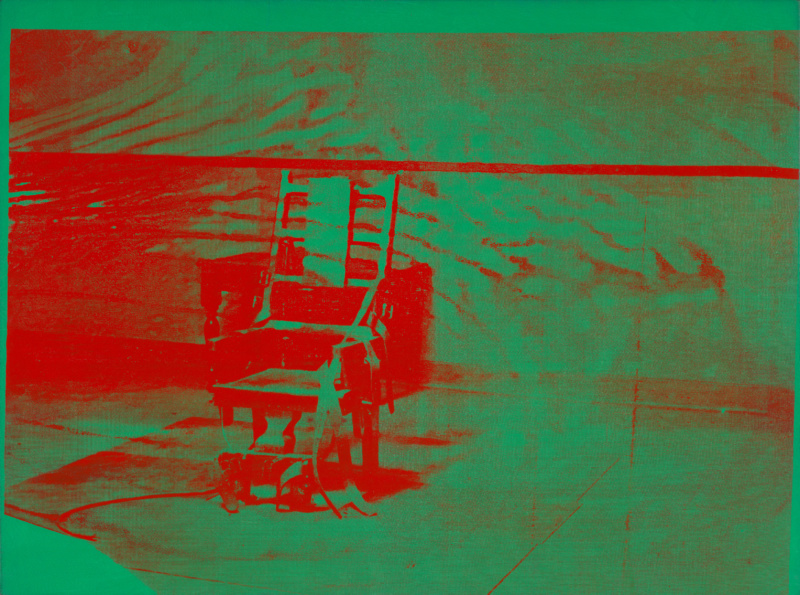

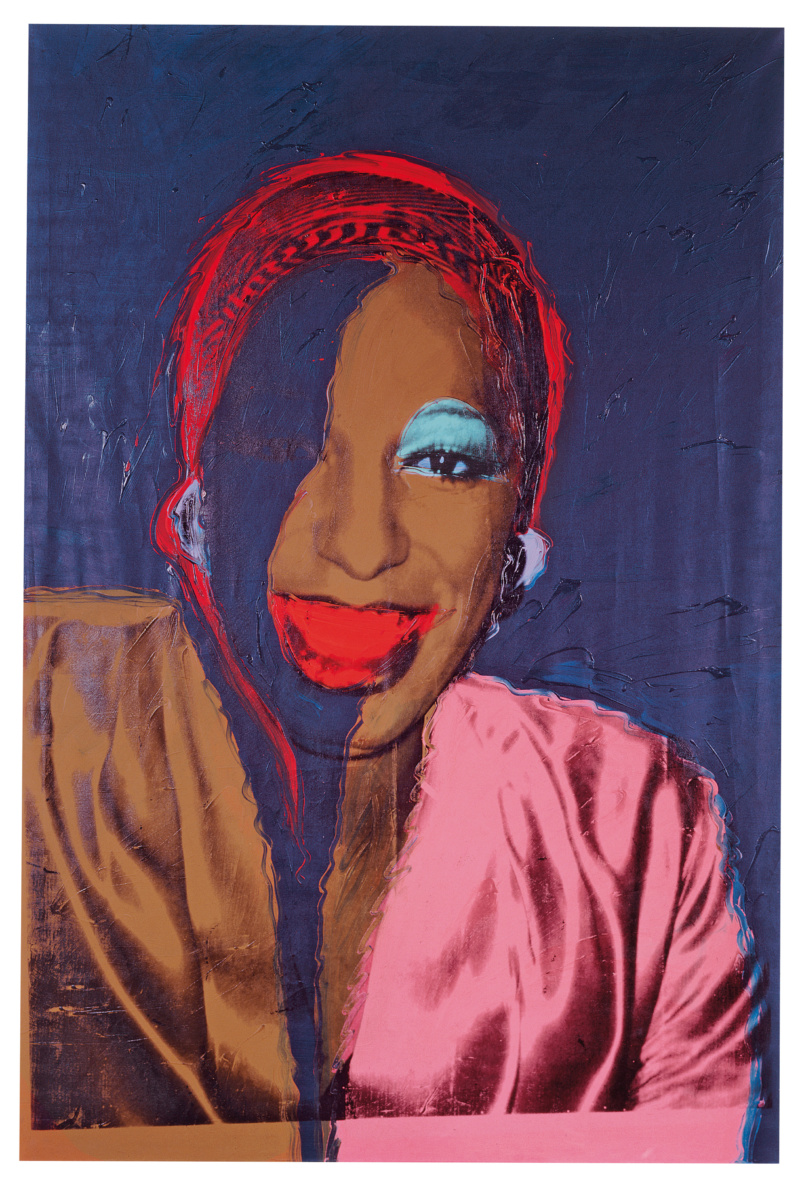

And the show deftly navigates the artist’s exhaustive range, a potential obstacle to its success as a Warhol retrospective could easily fill multiple venues. To be sure, there are plenty of hits— mediated and sequential images, experiments with abstraction, and Popism on full display. There is a sprawling tower of Brillo Boxes; the Jackies and Marylins; Coca Cola, electric chair and disaster paintings; the huge Mao; the Camouflage Last Supper; an entire first floor gallery dedicated to Warhol’s society and celebrity portraiture. But there is palpable surprise too, especially in a 1950’s section of lesser-seen works—Warhol, as it were, before Warhol, exploring his earlier commercial illustrations and more discernibly gay imagery.

The consummate insider and outsider, Warhol is known as a prescient social commentator and voyeur whose screen prints, film making and writing tackles race, sex, money, and fame, though notoriously circumspect about overtly political positions from a twenty-first century art view (with the exception, perhaps of the 1972, Vote McGovern). To mark the blockbuster event this week, we asked five Warhol experts— including the exhibition’s curator and Warhol authority Donna De Salvo— for their take on this major survey and why Warhol is timeless once again.

Courtney J Martin is the deputy director and chief curator at Dia Art Foundation which is currently presenting Andy Warhol’s Shadows (1978-1979) in Calvin Klein’s corporate 39th street headquarters. The show runs concurrent with the first six weeks of the Whitney’s retrospective and is the first time the series returns to New York City in 20 years. Shadows is a single painting in numerous parts, hung edge-to-edge around the periphery of the installation, as Warhol envisioned.

Why present Andy Warhol Shadows this fall in midtown? It’s important to have these works in New York because they have not been seen to this degree since 1998. The shadow paintings were last seen in Dia Beacon in 2014, but there is a whole generation of people in New York who have never seen them. And that, in it of itself, is a pretty significant venture which did not happen by chance. The Whitney’s chief curator Donna De Salvo has been a great friend to me and reached out a few years ago and said, “You know, I would really like to see Shadows on view when I’m putting up Warhol at the Whitney.” I said, “I would love to do that.” She hoped there was a possible way to do it in New York.

What does Dia’s project tell viewers about Warhol the artist? With Shadows, people are getting a chance to see that Warhol was not only a good painter— which is absolutely the case— but that he also cared deeply about the material of paint and the method of painting. On the one hand, you see someone who was working with two different processes, underpainting and screen printing. Some of the works are wildly painted with what almost looks like a mop, while others have a real gestural brushstroke. The different styles of painting suggest how much Warhol cared about the surface quality of the canvas. So even though there are 102 shadows in the series (48 of which are on view in midtown), I do not think any single one is exactly like any other one.

Eric Shiner is the former director of The Andy Warhol Museum in the artist’s hometown of Pittsburgh. Currently, Shiner serves as White Cube’s New York artistic director.

How do you situate Warhol in the zeitgeist of this particular moment? When you think about the world today, it’s not that different than the times that Warhol was inhabiting in the 60’s. There have always been major shifts and problems arising in mainstream culture. Warhol would sometimes choose to depict the players in those dramas as the subject of his work. I know he would have a field day certainly with what’s going on in our contemporary world.

Does his public persona somehow make it harder to present his artwork in a serious museum context? It’s definitely an important question to ask because he certainly can be very easily stereotyped as the artist who painted soup cans or Marilyn Monroe. Most people immediately associate Warhol with the wig and his outward appearance. However, that’s usually where it stops, and I always loved teaching and sharing Andy Warhol’s work with broader audiences who might be outside the art world and find him to be fascinating once they realize there was so much more to him. I think many audiences are blown away and say, “Wow, somebody focused on the mundane and the everyday.” It’s all very relatable.

How will a social media generation relate to Warhol? One of Warhol’s biggest dreams was to show his celebrity portraits in a huge grid at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that he would have titled Portrait of Society, a virtual beta version of Facebook. He was already thinking about these issues, documenting his life constantly through photography and audio recordings. He was definitely all about the democratization of knowledge and of secrets and gossip, showing the flaws, showing the cracks, showing ultimately that he was human, and if anything, that’s the beauty of social media that it still shows we are very human.

Blake Gopnik is a regular contributor to the New York Times, who recently published a feature about Andy Warhol’s role as a businessman and an artist immersed in commodification. He is writing a comprehensive biography of Andy Warhol forthcoming from Ecco at HarperCollins.

What should a Twenty-First Century Warhol retrospective achieve? Set up a Google alert for “Warhol,” and you’ll receive a flood of Warhol news every morning, proving that Warhol somehow matters to our culture more than maybe any other dead artist you could name. The big Whitney survey ought to let us find new ways to deal with Warhol since he’s so wrapped in cliche over the years.

If the Whitney show delivers a Warhol that we recognize too easily, then it has failed. If he is as great an artist as many of us figure he is, then he should truly contain multitudes, with something new to learn about him at every turn. In writing my biography, I have now studied him day after day, week after week, month after month, year after year, and I’m still surprised by him on a regular basis. I hope the Whitney so surprises its viewers that they forget to take selfies.

So what aspect of Warhol’s practice or persona remains the least explored to this day? I think that, at heart, Warhol was always a conceptual artist. He was disposed for it when he first hit the scene. But since then, his adoption into popular culture— and especially into the art market— have led people to do their best to bill him as a safe master of traditional esthetics. But if Warhol’s work isn’t making your brain hurt, then you’ve missed the point.

One of the enduring cliches of Warhol, coined already in his Pop Art days, was that he was his own greatest work of art. Sometimes cliches get things right. In this case, however, the cliche was born of the cutting-edge art thought of his era. Post-war artists were desperate to bridge the gap between art and life, and Warhol probably did it better than almost anyone else. It’s not going too far to say that many of Warhol’s works come close to being props in his “performance” of self than to being auction-worthy masterpieces. Don’t tell the auction houses.

Jessica Beck is the Milton Fine Curator of Art at The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Beck has contributed the essay, “Warhol’s Confession: Love, Faith, and AIDS” to the Whitney’s Andy Warhol— From A to B and Back Again compendium for the exhibition.

Could you say Warhol’s work was just waiting for 2018, ripe for this cult-of-celebrity age? I think Warhol, as early as the 1963 and 1964 moment, really understood the way that images circulate in the media, whether he’s working with disaster imagery, such as car accidents and photographs that would appear in Newsweek, or photographs of Jacqueline Kennedy before and after the assassination, either smiling in the parade or cloaked in a veil of mourning at the funeral. This notion of imagery circulation, fan identification, and simulation of the celebrity within image culture is now something that we live with so intensely, due to our proximity to fame through social media and Instagram, where we can actually comment on posts by celebrities on their specific pages.

When it comes to celebrity, a lot of Warhol focuses on issues of identification and projection of wish-fulfillment, aspirational ideas of perfection and beauty; class, wealth, and power. Now we have this new world. We’re all operating in a space where there’s an idea that we can have access to all those things immediately—even though we can’t.

Warhol was dealing with celebrity as commercial product. Today, you have a total collapse of personhood and advertising. Celebrities are posting about their relationship or photos of their children are tied to diaper ads, or Target launches of dishware. We are so wrapped up in it, it’s almost hard to see outside of the construct. But Warhol really got into the nitty-gritty of this, in a way that I think we can see so clearly now because we’re living it.

What does this retrospective and catalogue add to the volumes of Warhol scholarship already out there? The important thing that Donna has done with this exhibition is to ensure that her retrospective includes some of the works that were not in the last major US Warhol museum survey in 1989. For instance, Donna has included Warhol’s commercial work from the 1950’s. In fact, she did a 1989 show at the Grey Art Gallery called Success is a Job in New York. That was the first time that anyone had ever seen an exhibition venue display his commercial work.

The Whitney has also incorporated Warhol film and rigorously included different voices in their catalogue. In the past, when you look at Warhol scholarship, it can be somewhat male dominated. But I think it’s significant to remind everyone that women are talking and writing about Warhol too. For example, I wrote an essay for the catalogue about the AIDS epidemic in the 80’s, and how Warhol’s work operates within this intense cultural moment in New York’s gay community. Donna also brought Glenn Ligon to write for the book, expanding the scholarship to include artists which I think has a real impact on seeing Warhol in a more holistic perspective.

Donna De Salvo is the deputy director for international initiatives and the Whitney’s senior curator. She oversees Andy Warhol films catalogue raisonne project and curated Andy Warhol— A to B and Back Again.

Why now? Is there a renewed Warhol relevance? I think there is a new generation for Warhol, and that’s really important. It’s a generation that sees Warhol through an even heightened technological and digital culture lens than those before it. No one predicts history when you put these exhibitions on the schedule, but it does feel even more compelling and relevant to me, because Warhol reflects and records these contradictions in the US— the good side, the bad side, the bright side, the aspirational side, the anxieties. In some ways, he’s coming out of the postwar moment, but I think the work gets to the heart of many complexities about the United States.

In a way, this is a very formal exhibition, but one that also encompasses looking at all the different media that Warhol engages with. He’s the ultimate social observer. He doesn’t necessarily tell us what he’s thinking, but he puts it out there.

Is there a particular part of the show you advise people to note and slow down to observe? I hope that people will spend some real time in the room about the 1950’s because I do think you see a different Warhol at that time. First of all, you discover that he was an incredible draftsman. You see his own desires, and the vulnerability. His love of men comes through very clearly. I think that’s an important section of the exhibition because it sets up so much to see going through the decades, and that this coded language— that what you see is very much on the surface— but then beneath it, is all this other complexity. Like any artist, when you really follow the trajectory of their work, you have the capacity to understand more of the meaning behind it.

I think that it will be interesting to see visitors engage the Disaster works, which many people liken to history paintings. I consider them along the lines of the great realist painters, from Courbet forward.

But are the perennial favorites on equal curatorial footing? They’ll see the soup cans. They’ll see Marilyn. They’ll see Elvis. So yes, they are going to see great things they recognize. I’m a big believer that you have to show the public what they know, and then hopefully they’ll go to a place where they don’t know things. That’s always been my philosophy; as a curator, I respect my audience. People don’t have to come to a museum. There are a lot of other things they can do. And they don’t have to come to this museum. It’s really what you take away from it all. That was Warhol’s attitude: just look at the surface of my paintings if you want to know all about Andy Warhol. He’s a man who had the capacity to create extraordinary depth within surface, and to me, that’s the culture we live in.