Franklin Sirmans: So you have a big event coming up, right? Young Paris: The album. FS: Your next album is coming out. YP: Yeah. FS: It seems like you’ve been making an album a year, which is pretty impressive. There are certain things I think are important after listening to your music for a while now, and then listening to just a little snippet of Blood Diamond, it’s different! Where’s your head at? YP: I wanted to get into more of my poetic side, and a little bit more of the artistry of my songwriting. I feel like what I’ve been doing a lot the last several years has been creating more of a vibe, introducing this contemporary African sound and I think people are getting it now, so it felt like it was time to tell my story a little bit more. I’ve been doing the long route. I’ve been out here a long time. FS: I know! It’s impressive. YP: I’ve been able to survive by having my foot in so many different industries. Blood Diamond is looking at African kids, like myself, who come from conflict areas, and make it to America. The idea of a diamond, when you conceptualize it as a human, is like the African dream. We’re from the mud of areas of conflict, and we’re taken out and cut up and polished, and then we’re seen in a whole different light, to be displayed to the world as something beautiful. FS: Absolutely. YP: Blood Diamond introduces that conversation. My family is from the Congo and I’m talking about the way people live in Africa and then my journey here, and what it feels like to be an African who can sit front-row at a fashion show and be respected in these rooms. FS: You reference very specifically the idea of introducing yourself through Afrobeat and through the music and the image. You reference war within the song. There are some tough lyrics about people trying to grow up. It’s amazing to see that kind of a pivot. YP: The African story has not really been told in hip-hop; it’s hard to tell that story in American hip-hop. It’s hard to tell the first-generation African story. Now there are whole new generations who are making families here who have African bloodlines. A lot of us relate to knowing that we came from these countries and there’s a certain type of hustle that comes with that, a certain type of respect for bringing your traditional culture to a contemporary world.

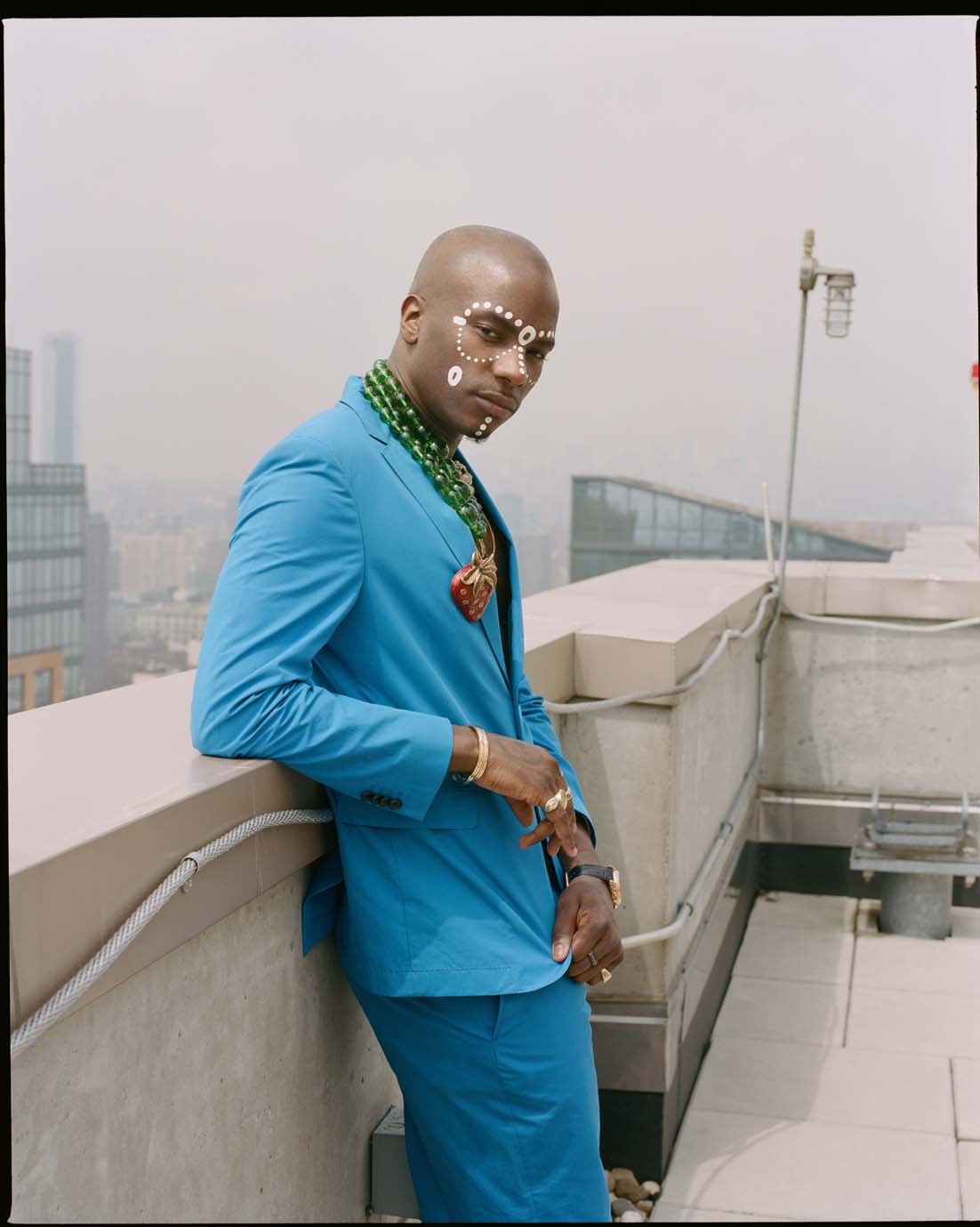

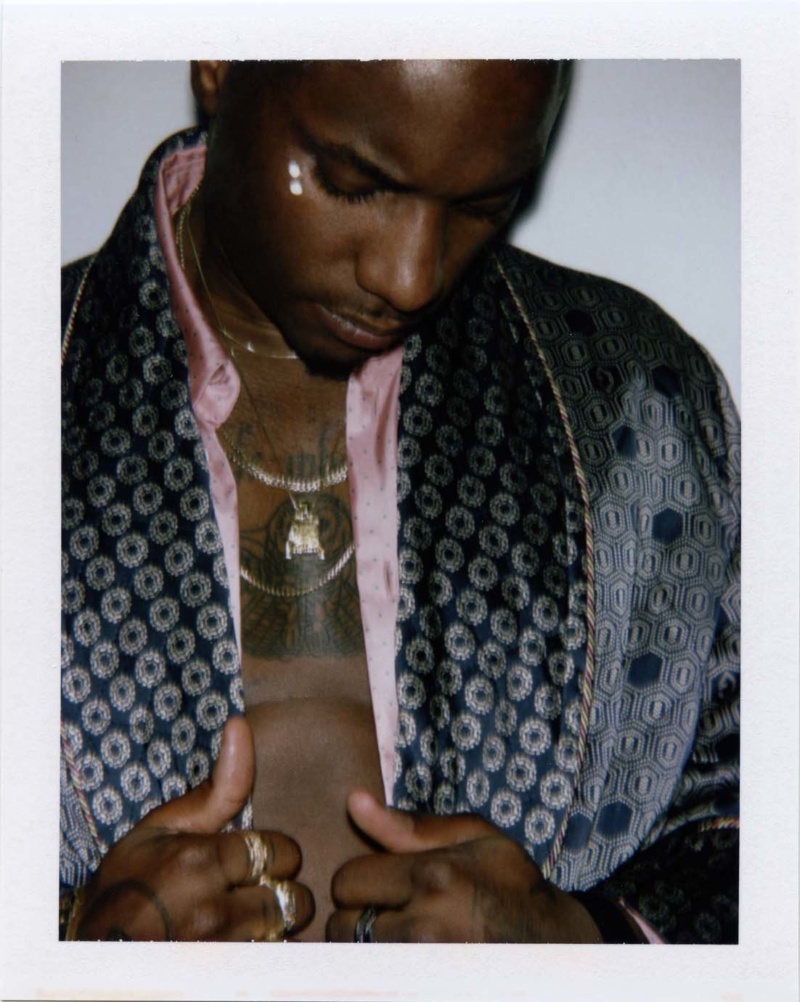

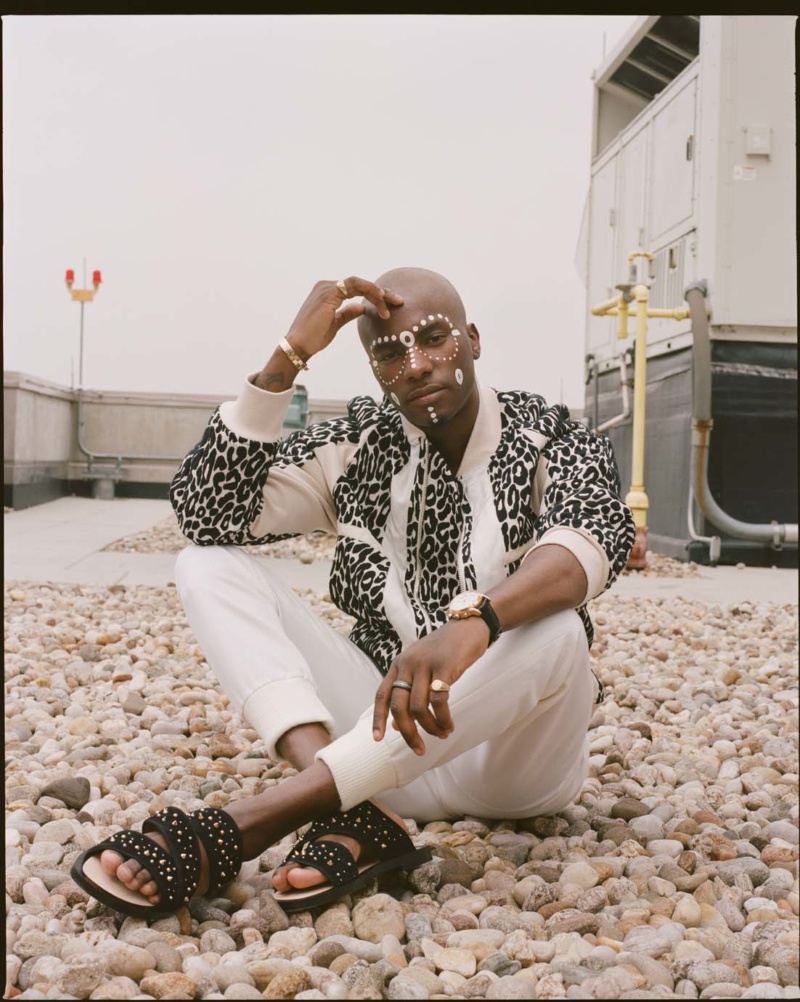

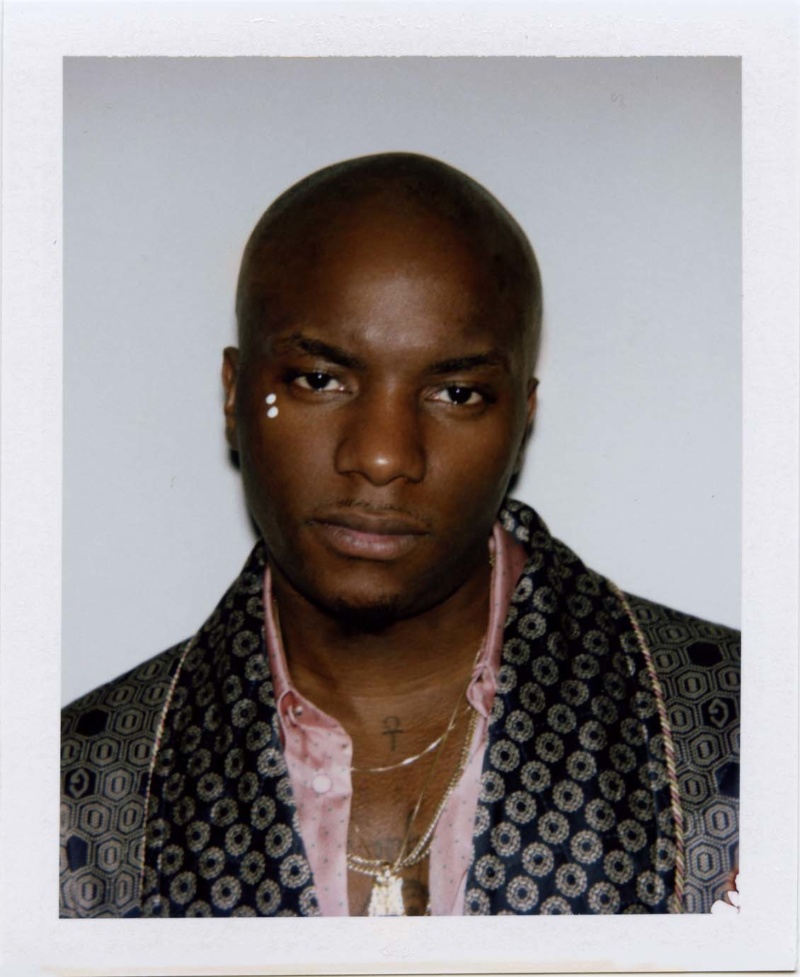

FS: Absolutely. You come from a pretty artistic background. Where did the desire for you to be a creative come from? YP: My whole life. My father co-founded the National Ballet of the Congo. The real Blood Diamond context is the story of my father, who came from a village in Congo. And when he created the National Ballet, he went to all these villages and said, we can create a performance and theater about what the country is doing, about the government and the police. At the time there was no media, no press; it was all about plays in the streets. My mother is also a dancer and we eventually moved to Paris, but I was raised in Congo where at times dinner was a struggle. It wasn’t a dangerous environment, but very traditional. Walking home at 2 AM when there’s no light, eating with your hands, eating the chickens that are in the yard, washing clothing by hand in the buckets. It’s completely natural. If you go to Africa today you have extremes. You have very wealthy Africans, and then over the bridge it’s a whole different world. FS: So, growing up you saw art and how it fits into people’s lives, but what was the first form of creativity for you? You didn’t really go into dance. YP: Well I did, actually. I watched my parents and was brought up in dance studios. It was a big influence. I started to dance, and when I say ballet is tradition, it’s really African dance. The boys in the family would play the drums and the girls would dance. I started as a drummer when I was around five years old. I was already keyed to these traditional African rhythms, and then we were living in the States and my parents would do these summer workshops. We would help with the choreography, and I started to do my own choreography. FS: Okay. YP: I started to sing and rap and when I was around 18 I started to really get into music. And then it was a good four years of figuring out what I wanted my sound to be, what my subject matter was, and how to start telling my story. My father was also a renowned painter; growing up with an artistic family, I was always involved with art in a household with 10 siblings where we were all dancing and painting—it was very colorful. FS: I’m wondering where your sense of image comes from. YP: I give a lot of credit to my father. He taught us to be proud of who we are, where we’re from, and before he passed he really drilled that into our consciousness. He was a very honorable man, someone we all looked up to. When I was a little older, we moved to Hudson, New York where there are lots of galleries, so I was a 15-year-old African kid going to art openings. FS: Amazing. YP: I would help with putting the shows together and the curators would explain things to me, like, this a Basquiat, this is a Dali. I was the only black kid. Being in those spaces and watching a show go up from A to Z and then come down, I just wanted to learn about why people create and I found my artistry through it all. FS: How would you describe your image? YP: I try to contemporize the African man. I try to celebrate the traditions, but keep it contemporary. I’ll wear Gucci, but have my paint on, or complement it with African garb. Whatever it is, it has to complement tradition. FS: The face-paint is a lot.

YP: Yeah, so the maquillage I use is a tradition. Specifically, we use it when someone dies or when a child is born as a way to renew energy. Energy never dies, it’s reused. When my father died, it was really hard for me. He was my hero and I needed to find a way to keep his energy with me. He had given me this maquillage when I was young and after he died, I just kept wearing it. Everybody was like, why you keep wearing your maquillage? I felt like he was with me. I did it so much, I decided to perform with it, and I started to do photos with it. It just became my image. He died in 2012. FS: I’m sorry, brother. YP: It was my way of grieving and holding onto a tradition. This has been done with a lot of different African traditions. In many ways it’s created a whole new identity for a lot of Africans or people who want to celebrate Africa. You see Beyoncé wearing it, you see a lot of superstars finding their way to kind of touch on Africanism. FS: Absolutely. It’s a way of making something representative of that space, too. You posted a beautiful quote on your Instagram from Chinua Achebe: “A man who pays respect for the greats paves the way for his own greatness.” You said that in relation to meeting up with Dapper Dan. YP: The young generation has to pay respects. The more the older and the younger generations communicate, the more we learn from each other. FS: Definitely. Does “Juicy,” the single that came out a couple of months ago, fit into the Blood Diamond conversation or is it more closely related to the past? YP: “Juicy” is the attitude of my sides. I got that Congolese confidence. I’ll do anything. And “Juicy” is a way of saying like, man, every day we finesse. We ain’t out here playing with nobody. This is New York City, I’m black in America. How do you think I’m making this happen? “Juicy” is away of talking about abundance, it’s fun. FS: Who did you do the video with? YP: A guy named AbFad from Atlanta. He’s a Sierra Leonean artist and he also directs. FS: The video is crazy. YP: I wanted to add in an element of artistry to make it a little bit more exquisite, with all the snakes and lizards and the girls looking like some African Game of Thrones shit. FS: Do you feel like that was part of what you were talking about in terms of establishing this presence within African music as a bridge to a global conversation? YP: The African Vogue album was about Africans basically creating what the idea of vogue is. It’s kind of us taking back the conversation. In one way, vogue is dance, an expression. It’s also the highest form of fashion. The album is a way of saying Africa is vogue. We are that. We make that. And then Afrobeats was about igniting the conversation of this contemporary sound coming out of Africa and playing the different avenues of it, doing the melodic forms, showing what upbeat feels like, telling this story from the raw. Now, Blood Diamond is the time to tell the story. Last night at Ozwald Boateng’s event, I was thinking about how it goes back to the concept of heroes. We need heroes. America is built on heroes, whether it’s a public figure, a brand, a business. In contemporary African culture we need more heroes. For guys like Virgil Abloh, it’s a big responsibility because there are a whole lot of people with your skin color that have high expectations. FS: For real. YP: You know he posted this thing the other day from his studio in Milan with the Off-White team, and obviously it’s in Italy so most of the team is white. But I was like, where are all the black people? We only really have Virgil. FS: In that space, yeah.

YP: You know, when Kanye was trying to do it, he didn’t have the empathy. It’s an empathetic job to be a hero. You gotta care about the people. The musicians have mastered it, black music has mastered it. We know how t tell that story, look at the fashion world, look at the art world, look at Hank Willis Thomas. How do we create that narrative? FS: We’re getting there, you know. Hank is a good one. The one thing I miss about New York is that it’s hard to find the other voices and there are so many of us in New York. You’re part of a much wider context and group of people here. YP: Yeah, that why I’m very keen to activate different spaces and encounter different groups of people. It’s not just about the music for me. It’s the conversation. As the pages turn, god kind of guides me. When I was nowhere, this girl, who I loved to death, was like, your image is incredible. I think you could do anything in fashion you want. And I was like, the fuck? [Laughter.] And she was like, I do PR. I didn’t even know what PR was. At first I couldn’t afford even the low rate she was charging me. I was scraping my bank account. She gave me the lowest rate of all her clients and that’s what I’m talking about when I say Blood Diamond. It’s someone seeing the glass and being like, that is some shit down there. If I polish that shit— FS: It’ll shine. YP: And it’s not about race or whoever. It could have been a black woman. It could have been anyone. FS: It’s about someone acknowledging. YP: It’s about someone acknowledging something that I had that I couldn’t see myself, and giving me the battery to think about doing a campaign or an editorial. FS: It’s true. YP: Having these experiences, knowing what it’s like to be completely in doubt and insecure. To be ashamed of being an African. All of this goes into the journey. FS: It’s interesting—the contrasts you had in your foundational moments are what allowed you to see the world. YP: Yeah, growing up around white people and Africans, and living in Congo and Paris and then in New York and going to these electronic parties and nightclubs. FS: I love it. YP: I’m completely comfortable in all those spaces. If you follow my Instagram, you don’t know what the next post is gonna be. You might see me standing next to the goddamned president, like, oh shit. Or you might see me with some kid in the hood. I celebrate everyone. That’s what art is. It’s about

YP: You know, when Kanye was trying to do it, he didn’t have the empathy. It’s an empathetic job to be a hero. You gotta care about the people. The musicians have mastered it, black music has mastered it. We know how t tell that story, look at the fashion world, look at the art world, look at Hank Willis Thomas. How do we create that narrative? FS: We’re getting there, you know. Hank is a good one. The one thing I miss about New York is that it’s hard to find the other voices and there are so many of us in New York. You’re part of a much wider context and group of people here. YP: Yeah, that why I’m very keen to activate different spaces and encounter different groups of people. It’s not just about the music for me. It’s the conversation. As the pages turn, god kind of guides me. When I was nowhere, this girl, who I loved to death, was like, your image is incredible. I think you could do anything in fashion you want. And I was like, the fuck? [Laughter.] And she was like, I do PR. I didn’t even know what PR was. At first I couldn’t afford even the low rate she was charging me. I was scraping my bank account. She gave me the lowest rate of all her clients and that’s what I’m talking about when I say Blood Diamond. It’s someone seeing the glass and being like, that is some shit down there. If I polish that shit— FS: It’ll shine. YP: And it’s not about race or whoever. It could have been a black woman. It could have been anyone. FS: It’s about someone acknowledging. YP: It’s about someone acknowledging something that I had that I couldn’t see myself, and giving me the battery to think about doing a campaign or an editorial. FS: It’s true. YP: Having these experiences, knowing what it’s like to be completely in doubt and insecure. To be ashamed of being an African. All of this goes into the journey. FS: It’s interesting—the contrasts you had in your foundational moments are what allowed you to see the world. YP: Yeah, growing up around white people and Africans, and living in Congo and Paris and then in New York and going to these electronic parties and nightclubs. FS: I love it. YP: I’m completely comfortable in all those spaces. If you follow my Instagram, you don’t know what the next post is gonna be. You might see me standing next to the goddamned president, like, oh shit. Or you might see me with some kid in the hood. I celebrate everyone. That’s what art is. It’s about