For the 2019 Whitney Biennial, curators Rujeko Hockley and Jane Panetta spent a year traveling, visiting artists in their studio, searching for work that resonated with the times—crucially and energetically (and sometimes optimistically). It's one of the youngest group of artists in the Biennial's history: of the 75 artists and collectives included, three-quarters are under the age of 40; only five have exhibited in a Whitney Biennial before.

Among the participants are plenty of our favorites—beloved artists we’ve interviewed and think of as part of the extended Cultured family. Revisit their coverage here, and find their work when the Whitney Biennial opens this Friday, May 17.

Simone Leigh As Elizabeth Karp-Evans explains in her profile of sculptor Simone Leigh—the first black artist to win the Hugo Boss Prize, last October—“her rise is as much a story of an artist who has elevated the medium of sculpture as it is of someone who has acknowledged and uplifted the black female experience in contemporary art.” Leigh agrees: "I’m standing on the shoulders of many that got me to this place… they also modeled how you can hold the door open for others," she says. "That’s part of my job now.”

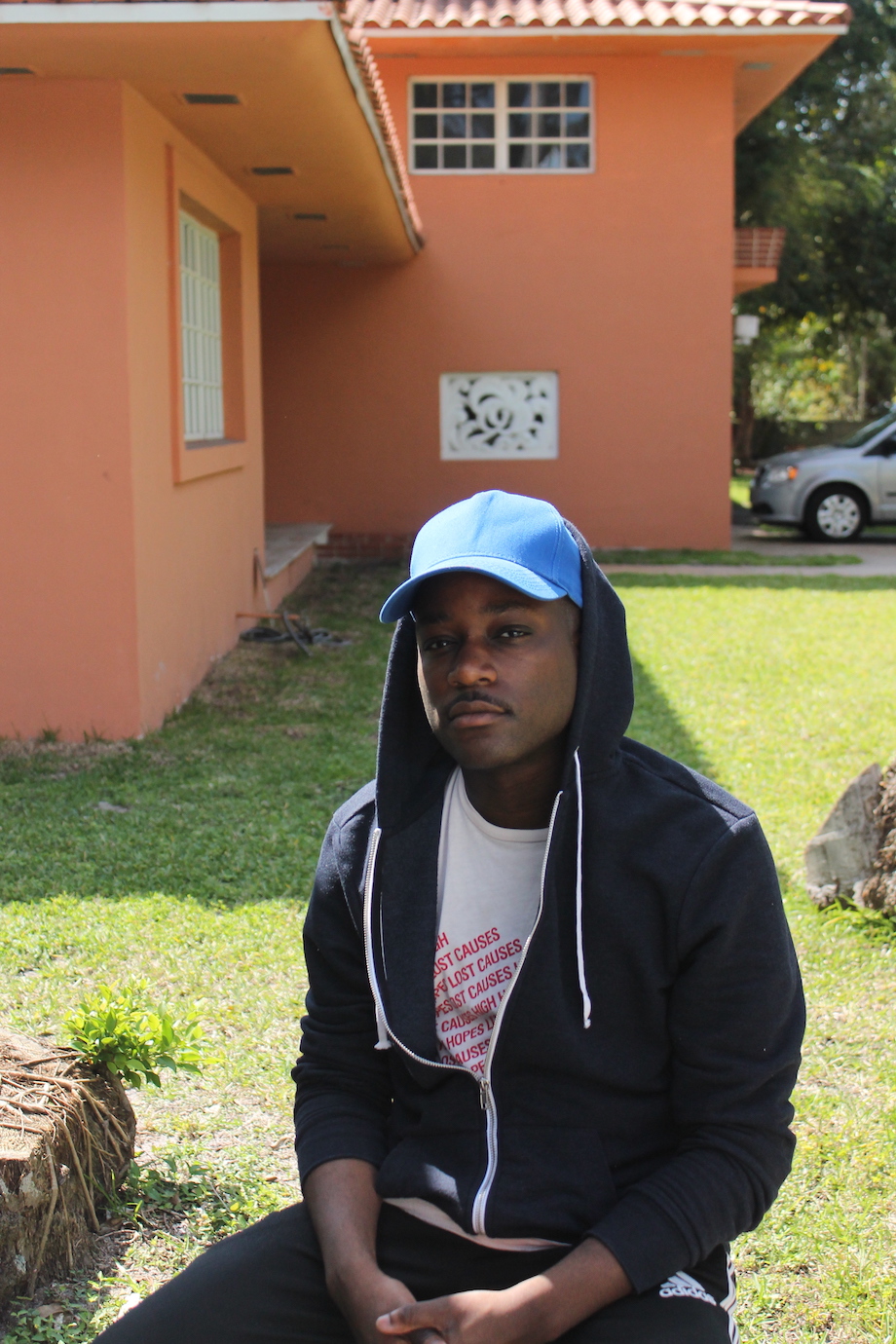

John Edmonds John Edmonds has been taking photographs since he was a teenager; his intimate work, primarily of black men, “embodies the complexity of our social, political and personal mythos of the black body in a beautiful and subtle way that stays with you, like Moonlight,” says Mickalene Thomas, in Antwaun Sargent’s profile of the artist. As Edmonds explains it: “Making photographs is like a way to learn how to see or understand how you see the world around you.”

Elle Pérez In Elle Pérez’s photographs, "the state of becoming" is always present, writes Em Gallagher. Their work encapsulates gender and identity, tenderly and with real love: "When it comes to the identity of the person, what if all that weight could exist in the composition?" they ask in the story above. "What if it could liberate the people in the photographs from having to claim anything?"

Meriem Bennani Meriem Bennani, who works primarily with video and animation, explores the future—and the constantly shifting present—with absurdity, humor, and a glowing sense of surrealism. In this interview with Kat Herriman, Bennani says her work "is 100 percent intuitive to start with." Given its multifaceted nature and her multitude of ideas, some of it goes unrealized: "It’s very important to constantly have unrealizable projects. There is a full reality TV show season I have started preparing and never realized, but most of the materials I have written for it go into other projects." Probably like her satirical piece, Fardaous Funjab.

Calvin Marcus “People say some of the things I make are ‘weird.’ I think that they’re weird too, but the thoughts most people have are weird,” says Calvin Marcus, as interviewed by Williams J. Simmons, encapsulating both the strangeness and distinctly human quality of his work. “If we do find ourselves inside his work, what might we find?” asks Simmons. “It might be scary or confusing or beautiful, and that is a risk Marcus invites us to take.”

Ilana Harris-Babou Playful cooking shows (made with her mother) that cite Audre Lorde's "Uses of the Erotic"; a commercial calling for reparations for black Americans—disguised as a promo spot for a luxury furniture store making the old new again: Ilana Harris-Babou likes, she says, “to to use humor and familiar forms as a Trojan horse to get heavier material into people's line of sight.”

Janiva Ellis Janiva Ellis’s paintings are almost psychedelic, cartoonishly bright and carrying with them large, profound narratives: “Pairing the communicative immediacy of cartoons with the urgency of gesture can spawn a tense formula in art that activates the environment in which the characters engage,” the artist says in this profile. “Cartoons reference our introduction to media and how that influences our perception. Tactics of categorizing as a means of self-preservation begin with our earliest exposures to media.”

Eric N. Mack Eric N. Mack's work takes readymades, particularly textiles and one-off objects, and transforms them into something poetic, moving, and alive. “The joy of Mack’s multimedia sculptures is their uncanny formal balance, which seems to give familiar objects renewed meanings,” writes Herriman in their interview here. “One marvels at the memories and association that a painted pistachio shell can set off.”

Martine Syms In the work of Martine Syms—who was one of our recent cover stars—you'll find, writes Simmons, "interventions into new media that have profoundly changed the nature of the art-historical landscape. What is equally important is Syms’ role as a researcher and writer, as someone who brings the past, with all its complexities and paradoxes, into the present." Some of those paradoxes are contained in Syms's own existence; she says she's "often asked, required or demanded to take on multiple positions in life. These are the conditions, and given that, what do you do? How do you live? This is one of my animating questions.”

Jeffrey Gibson In Ted Loos’s profile of the painter Jeffery Gibson, the artist earnestly outlines his creative goals: “It’s representation…Until I see clear representation within popular culture of indigenous people and aesthetics, then my pursuit is not done, you know? It’s that simple.” Simple, yes, though Gibson also continually re-examines the storylines associated with every part of his identity: “It’s always been about using my personal narrative to complicate the popular notions of being queer, being gay, being Native American—any of these singular adjectives.”

Brendan Fernandes In this conversation between Brendan Fernandes and the collector Anne Huntington, Huntington revels in awe of the multidisciplinary artist: “Every performance and exhibition of Brendan’s highlights the breadth and depth of his practice.” Weaving dance—Fernandes professionally trained as a ballet dancer—performance, and even the reinterpretation and re-staging of collections (Lost Bodies, 2016, at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre) Fernandes gracefully repositions the systems and structures that have, for too long, attempted to define us.

Jenn Nkiru Jenn Nkiru’s “visual language has captured the moment by combining found footage, assemblage and a surrealist dreamscape-infused aesthetic that seeks to redefine the way we see blackness,” writes Amah-Rose Abrams. In BLACK TO TECHNO, a short documentary—the film was a commission with Gucci for Frieze L.A.—Nkiru explores “the roots of techno music in Detroit…‘Music heads know that techno is a black sound and that it started in Detroit.’” Though she is primarily a filmmaker, she never wants “to pigeonhole myself by using one medium. For me, the biggest thing is the message.”

Madeline Hollander For dancer and choreographer Madeline Hollander—who recently choreographed the jerky body movements of the uncanny doubles in Jordan Peele’s Us— choreography is "all around us." She, writes Herriman, "operates like a scientist. Her performances begin with months of research, followed by rigoorus testing and dissection in the dance studio." As Hollander puts it: "My process is definitely closer to an examination than invention."

Agustina Woodgate Agustina Woodgate’s multidisciplinary practice, writes Monica Uszerowicz, is “fueled by an impassioned, electrically-charged curiosity…Woodgate researches and digs; then researches some more. Her work comes less from creating, and more from deconstruction—from discovery and inquisitiveness, from communication. She often thinks about territories, their politics and boundaries, how they might be physical or imagined.”

The 2019 Whitney Biennial, organized by Jane Panetta and Rujeko Hockley with curatorial project assistant Ramsay Kolber, is on view from May 17 through September 22.