It was in the summer of 1997 that the purple-prose catalog impresario John Peterman first contacted 20th Century Fox regarding the upcoming release of James Cameron’s teen-pleasing disaster epic, Titanic. The film’s future had come into question via a whisper campaign suggesting calamity: over budget by nearly $100 million and behind schedule by five months, Titanic was initially rumored—like its namesake—to be a colossally expensive mistake. But Peterman felt an immediate affinity for its Edwardian nostalgia, and proposed a deal that the studio couldn’t refuse. The sentimentality salesman felt certain he could do a brisk business shilling trinkets snatched from Titanic’s narrative in Peterman’s Eye, an arrangement designed to both ameliorate the film’s debt and bolster its already flagging public profile.

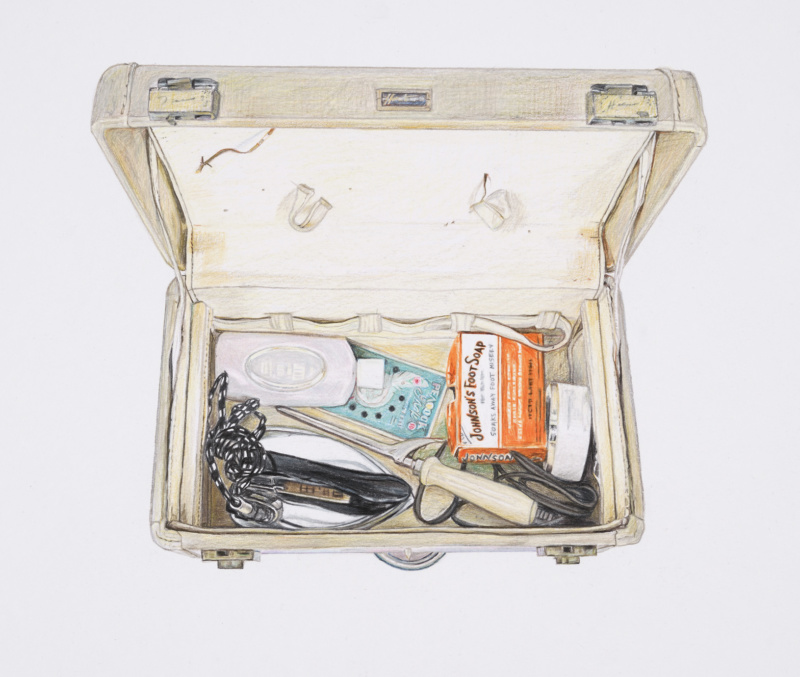

By February of 1998, the film had proved its naysayers wrong, grossing nearly $1 billion at the box office. The spring issue of the Peterman’s Eye catalog (a publication which itself found a degree of fact-fiction crossover on Seinfeld) featured 25 pages of original and replica props and costumes that seemed to have bobbed up from the bottom of the cinematic ocean. The resulting faux-moth-eaten mise en abîme allowed anyone with a Mastercard the opportunity to wander the corridors of their schlocky Gilded Age fantasies. Amid a glut of beaded charmeuse dresses (offered with matching red satin “life affirming” boots), water-damaged luggage and an assortment of historically accurate White Star dinnerware was the item that sparked immediate desire in the souls of would-be Rose DeWitt Bukater cosplayers everywhere. Presented in a hinged case and accompanied by an official letter of “authenticity” was a $198 reproduction of the film’s MacGuffin: a gigantic heart-shaped cubic-zirconia pendant that hung, boulder-like, from a rhinestone-studded chain.

Peterman would later claim to have sold nearly $1-million worth of Heart of the Ocean replicas; a passionate group of people wanted to insert themselves into a fictitious narrative of romantic suffering at the center of the ship’s lore. The necklace’s fame imbued its 75-carat imitation-diamond centerpiece with a surplus of meaning that worked to magnify its double artificiality: everyone already understood that the real fake Heart of the Ocean never existed, that its own gleaming bulk was nestled for eternity in the murky depths of the film’s CGI wreckage. What Cameron’s movie and Peterman’s flamboyant bauble threw into sharp relief is the enduring lust the public has for material points of contact that directly intersect with their illusions of emotional intimacy.

Passion for the historical details of the RMS Titanic tragedy multiplied in tandem with the popularity of its cinematic retelling, but it was by no means an obscure object of inquiry before. The disaster, which was the first to be covered in real time, courtesy of the wireless telegraph, has thrummed the strings of public obsession ever since the earliest reports of the ship’s failure. Titanic enthusiasts organized appreciation societies as early as the 1960s, and the vessel continues to generate both revenue and myth. Over the past 30 years, thousands of artifacts have been recuperated from the Titanic’s North Atlantic grave, and though many of these items derive their auras from their physical degradation, there are examples that are saturated with a relatable brand of romantic doom.

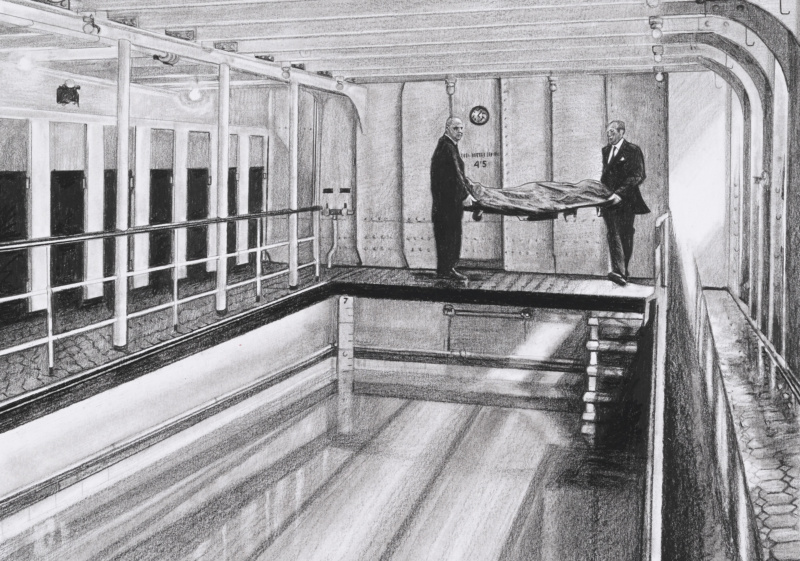

Timed to coincide with the centennial of the sinking, the largest-ever sale of salvaged Titanic artifacts was conducted at Guernsey’s in April 2012. A group of 5,500 items sold en masse to a single buyer, the Titanic Collection included a large section of the ship’s hull, a decorative bronze cherub that once leered at passengers as they descended the grand staircase, and a corroded pocket watch frozen forever at 11:50. Though each of these items drummed up its own frenetic publicity, there was one object that continues to captivate Titanic romantics everywhere: a small rose-gold bracelet with the name Amy spelled out in diamonds.

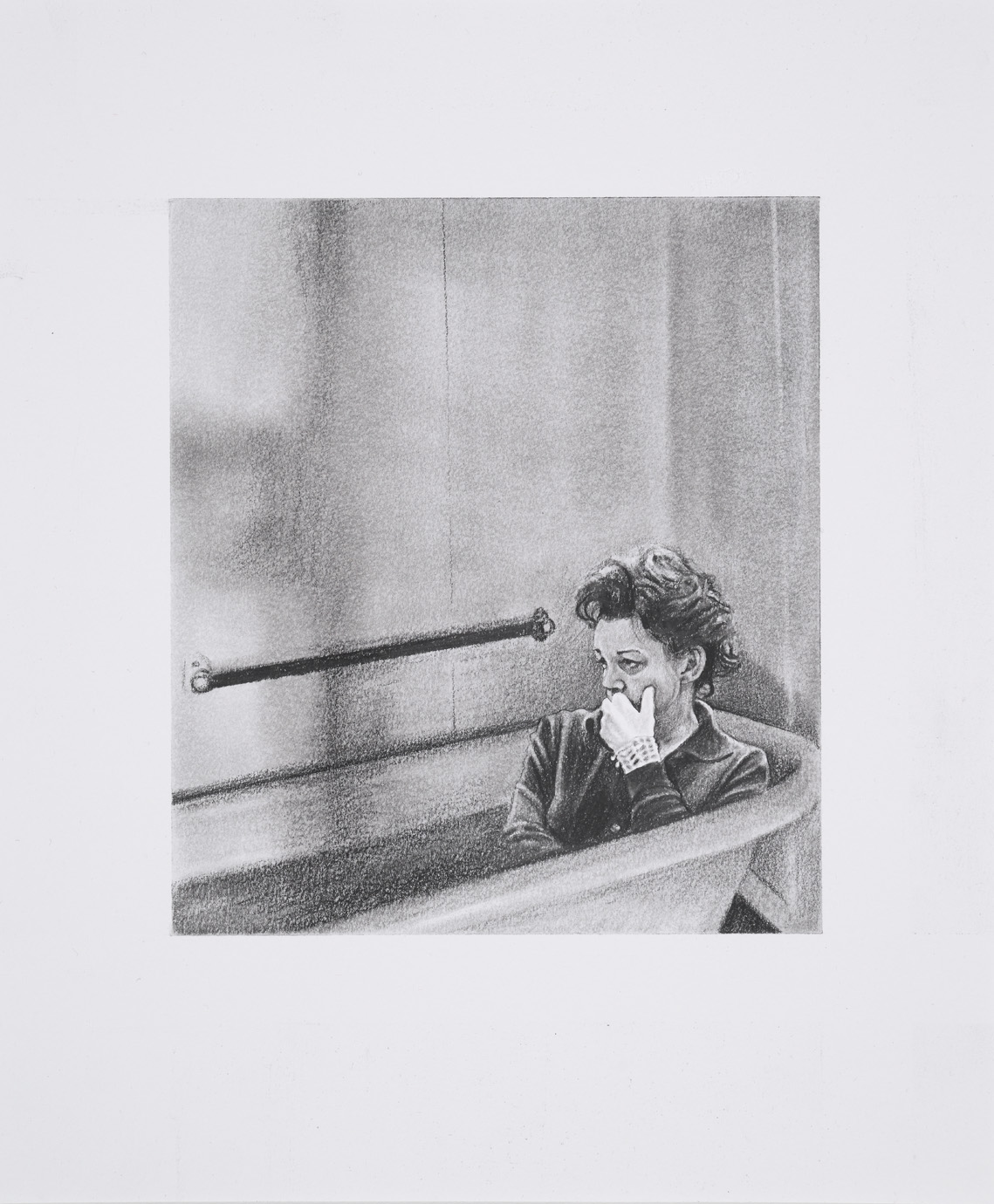

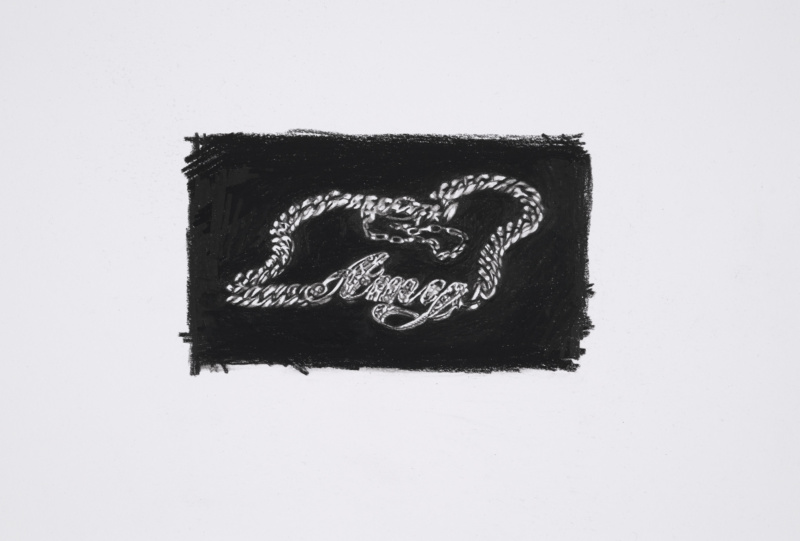

Brought to the surface in 1987, the bracelet made its public debut on Return to the Titanic, a heavily hyped (and heavily scripted) special that aired live from Paris on October 28 of that year, one month following its recovery. Hosted by actor Telly Savalas, the program featured a panel of eveningwear-clad experts who examined a selection of the ship’s sodden goods and offered thin speculation on values and origins. Situated next to a plastic tub filled with black clods of disintegrating banknotes and a bucket of tarnished coins, Amy’s trinket seemed to metonymize the romantic pathos that clings to the ship’s corroding corpse. It was a perfect artifact, an open signifier that invited a starstruck public to dream up a thousand stories of ill-fated love.

Message boards devoted to uncovering the mysterious origins of the bracelet include alphabetized passenger manifests (there were only two Amys aboard, but there was also an Amelia and an Amanda) and speculation about relatives and middle names. They discuss circumference and wrist sizes and offer reverse-inflation calculations to determine what type of person could have afforded such a jewel. The most fascinating theories point to a first-class passenger named Richard Leonard Beckwith, who was rowed to safety with his wife, Sally, and his stepdaughter, Helen, in lifeboat 3; his initials match those monogrammed on the Gladstone bag that the bracelet was found in. On that evidence alone, observers posit an illicit affair. Beckwith’s family, for what it’s worth, has steadfastly denied he had any relationship to the bag or the bracelet, but that doesn’t stop anyone from spinning romantic yarns about the dead man’s philandering. The bracelet, along with the rest of the items included in the Guernsey’s sale, sold for an astounding $200 million. It probably seemed a reasonable price to the devotees who have to content themselves with dreaming about Amy, a girl who never received the token of affection from her married lover’s international journey.

It was, I must confess, the Amy bracelet that drew me to the Titanic (and Titanic). Though I have long had a great passion for auctions of often-obscure belongings of dearly departed Hollywood stars, I had never seen Cameron’s film nor had an interest in the ship itself until a few months ago, when I happened upon images from the Guernsey’s sale. I was immediately struck by how contemporary the bracelet looked, by how much it would have suited Amy Winehouse’s tenderhearted bad-girl style, and I could not shake the similarities with another object that stirs the embers of my heart: lot 409 of the Julien’s 2012 “Icons & Idols” sale.

Fans of Brittany Murphy will perhaps recognize lot 409. Mounted in 14-karat white and yellow gold, the words “Joe” and “Brittany” are rendered in pavé diamonds and surrounded by three bubbly hearts in the same name-plate design as poor Amy’s lost bracelet. The necklace serves as a relic of Brittany’s short-lived engagement to production assistant Joe Macaluso, a whirlwind romance that churned its way through the tabloids in under a year, before it was eclipsed by the actress’s squalid marriage to a con artist named Simon Monjack. Brittany’s mother put the necklace up for auction two years after her untimely death. Sandwiched between Murphy’s canceled passport and a painting of a clown by comedian Red Skelton, the necklace hammered at $1,408 after just 10 bids.

It was a meager result that seems out of balance with the maelstrom of drama that simmers beneath the object’s tacky early-2000s surface. Symbolic of the actress’s waning popularity and her subsequent demise, the necklace to me presents as a perfect metaphor for her flash-in-the-pan style of celebrity, one that doesn’t last and is all the more touching for it. While it is Murphy’s slow egress from fame that imbues the object with meaning for a person like me, it also perhaps saps her memorabilia of value. She was not an unsinkable ship, just an already-damaged commodity that had trundled slowly off the radar.

The modest results of the Murphy sale stand in stark contrast to the record-breaking 2016 Marilyn Monroe auction at Julien’s, which featured 1,025 of the actress’s personal belongings and memorabilia. Few objects in Hollywood history approach the mythological infamy of the dress Monroe wore when she serenaded John F. Kennedy at Madison Square Garden in May 1962. Just three months prior to her death, the event has become emblematic of the star’s sensuality and the shambolic disasters that typified her personal life. The nude-colored transparent gown emblazoned with hundreds of spherical crystals hammered at $4,600,000, the highest price ever paid for a slice of the dead actress’s suffering.

I consider the Titanic vessel an important figure in the pantheon of doomed starlets, because its expensive and seemingly infallible body shocked the world when it crashed and burned. Like Monroe, like Harlow and Mansfield, the public was ill-prepared for disaster to eclipse the glamour contained by the ship’s promises. To want to wear Harlow’s perfume or use the same Erno Laszlo cream that sat next to Monroe’s deathbed is not so dissimilar to wanting to own a replica of the Heart of the Ocean. For those of who will never touch the Amy bracelet, it probably seems close enough.

Just like the rumormongers who questioned the circumstances of Monroe’s downfall, conspiracy theorists have long suggested that there was something foul afoot when the unsinkable Titanic disappeared beneath the ocean. I recently watched a documentary made by British historian Tim Maltin, whose lifelong fascination with the Titanic led him to investigate the weather conditions off the coast of Newfoundland on the night of April 15, 1912. Scouring captains’ logs and firsthand accounts, Maltin discovered that a sudden temperature shift wedded with an unusually clear night sky likely triggered an optical illusion that obscured the iceberg lurking fatally on the horizon. Comparing the stars to city lights viewed from afar at night, Maltin described a phenomenon called “scintillation,” which produces a destabilizing twinkling effect that would have made it difficult to differentiate the water from the sky. I thought immediately of Monroe’s last big night out, standing on a stage in her see-through dress and shimmering under a spotlight as she sang “Happy Birthday” to a man everyone already suspected was her lover. She was, I suppose, scintillating, unable to see that the course she charted could lead to nothing but catastrophe.

in your life?

in your life?