Chris Gartrell: Britney Spears has been a household name for over twenty years. We all hold her in our consciousnesses, whether as the eager teenager bursting through our screens on TRL at the dawn of the new millennium, the fallen star gracing every supermarket tabloid in the later 2000s or the stalwart Vegas icon and recluse of recent years. Though it goes without saying that Britney is a living legend, her accomplishments only scratch the surface of what makes her important. Her star has burned so dramatically that it can be hard to see the profound cultural significance hidden in the shadows of her life and work. But, to look closely is also to hold the mirror up to ourselves, especially now.

Phoebe Berglund: To take a closer look at Britney, we must first take her seriously as an artist and trust that she is cognizant of the messages in her lyrics, images and movements. What happens when we analyze Britney on that level? I think of the moment in 2007 when she attacked a paparazzo’s SUV with an umbrella: Britney as Viennese Actionist! What if the umbrella is to Britney what the urinal was to Duchamp?

I live in New York City and I work in the contemporary art world, the biggest urinal of them all. Due to COVID-19, my exhibitions have been cancelled. Time and space as we knew them have collapsed and, like many, I am unemployed and home for most of the day. While scrolling through my iPhone, I find myself thinking about Britney, a cultural figure who has been in isolation for most of her life. The videos on her Instagram remain the same—a repetition of dance aerobics performed in her Rococoesque living room and outfits modeled in her Grecian garden—because her cloistered existence is essentially unchanged by quarantine.

On March 23, however, Britney posted something remarkable: a text piece by internet artist Mimi Zhu that called for a “general strike” and the “redistribution of wealth.” Britney’s caption read “communion goes beyond walls” and was accompanied by three red rose emojis. The roses could simply refer to her love of flowers, which are a central subject in her painting oeuvre (sometimes a rose is a rose is a rose), but the rose symbol has also been used as a logo by socialist political parties since WWII. The internet was shocked by her post, but I wasn’t.

CG: Running with this image of Britney as revolutionary catalyst, in April she posted a video on Instagram about burning down her private gym (“I had two candles and one thing led to another”); though I’m sure the fire was accidental, there’s something wonderful about Britney burning down the gym as an analogy for Britney burning down the whole system, perhaps even brandishing her favorite Yankee Candles in an act of creative destruction.

PB: It reminds me of when John Baldessari burned all of his paintings in 1970, an inferno titled Cremation Project. The gym is really Britney’s artist studio. As a performer, the body is central to her practice and in order to maintain her physique she spends several hours a day sculpting it.

CG: Britney’s life-as-practice is articulated entirely within the home and on Instagram. Her experience of isolation goes beyond that of a typical celebrity because she has essentially been held captive for the past decade-plus. She is under a legal conservatorship, which gives her father control over her affairs and finances, hence the increasingly visible #FreeBritney movement. This arrangement likely would not have been imposed if she weren’t rich and famous: in other words, if her family and management hadn’t wanted to continue making money off Britney-the-brand in the wake of the nihilism that she enacted around her Blackout album cycle in 2007-08. We don’t know all the details of Britney’s mental health struggles (nor are we entitled to), but many have questioned the ethics of pushing her to continue working as a pop star following her public breakdown and involuntary hospitalization.

Since late 2008, Britney has seemed different, like a visitor in her own skin and image. I think of the “other side” in Twin Peaks, especially in the recent third season, and the representation of a kind of awful American subconscious that shatters people, leaving them hovering between the shadows of suburban Las Vegas and the towers of Manhattan. Britney returned from the abyss and was pulled back into the unstoppable machine of her own iconicity. The MTV News special Britney: For the Record, released in November 2008, offered a rare and candid assessment; Britney stated for the camera: “Even when you go to jail, you know there’s the time when you’re gonna get out. But in this situation, it’s never-ending. It’s just like Groundhog Day every day.” (New theories emerge with each new Instagram post: is Britney’s interpretive dance to “Never Ending” by Rihanna actually an ingenious way of quoting herself and commenting on her conservatorship?) Hits from this latter phase of her career, like “Till the World Ends” and “Work Bitch,” take on a sinister tone when considered as anthems for the relentlessness of her fame and the pressure to keep working (and dancing), no matter the personal cost.

Everyone can relate to this type of pressure on some level. Most of us have had essentially no choice but to keep working and spending in order to ward off whatever abyss or utopia might await us on the other side. We are kept so busy that we don’t even have time to imagine what else could be. In this sense, Britney’s life and career reflect a more widespread experience of existence under late capitalism. Her trajectory mirrors the last twenty years of American culture almost more than anyone’s, and I think we see a lot of ourselves in her, as an archetype for burnout.

I’m also thinking about how shady music industry labor practices, especially the questionable involvement of family members and unscrupulous managers, have been many a pop star’s Achilles heel. It took years for Beyoncé to sever business ties with her father, Mathew Knowles; Colonel Tom Parker arguably ran Elvis’s career into the ground and, notoriously, Joseph Jackson was an abusive patriarch who forced all nine of his children into the entertainment business at very young ages. Michael and Janet Jackson broke free of his grip as they became superstars in the 1980s, but both spoke out about carrying the pain of that relationship well into adulthood.

Janet’s breakout album Control (1986) was released as a statement of independence at the same time that she fired her father as her manager. In the spring of 2019, Britney posted images from a photoshoot in which she is styled after the Control album cover: red background, angular black dress, facial expression all business, big hair draped over one shoulder. I think it’s worth considering that Britney is Janet’s pop heir in many ways (in her dance technique, her vocal stylings and her fashion sense), though most people think first of the Madonna/Britney succession, an all-too-convenient lineage of whiteness and blondeness that was publicized in the early 2000s. The work of Black cultural producers is so often erased that even someone as hugely influential as Janet gets overlooked in Britney’s story; but, here—as at several junctures in Britney’s career—Janet is the blueprint, in this case for symbolically breaking free from the confines of a paternal work trap.

A few months prior to this Control-inspired post, Britney had announced an “indefinite work hiatus,” canceling her latest Vegas residency, “Domination,” before it even began. While the circumstances behind these events remain mysterious, I do wonder if Britney is happy to be free of work. Does she feel emancipated from the Britney machine? Has she gained a new perspective? I wonder what the world looks like to her now that the concept of indefinite hiatus is basically global. Has Britney been anticipating collapse?

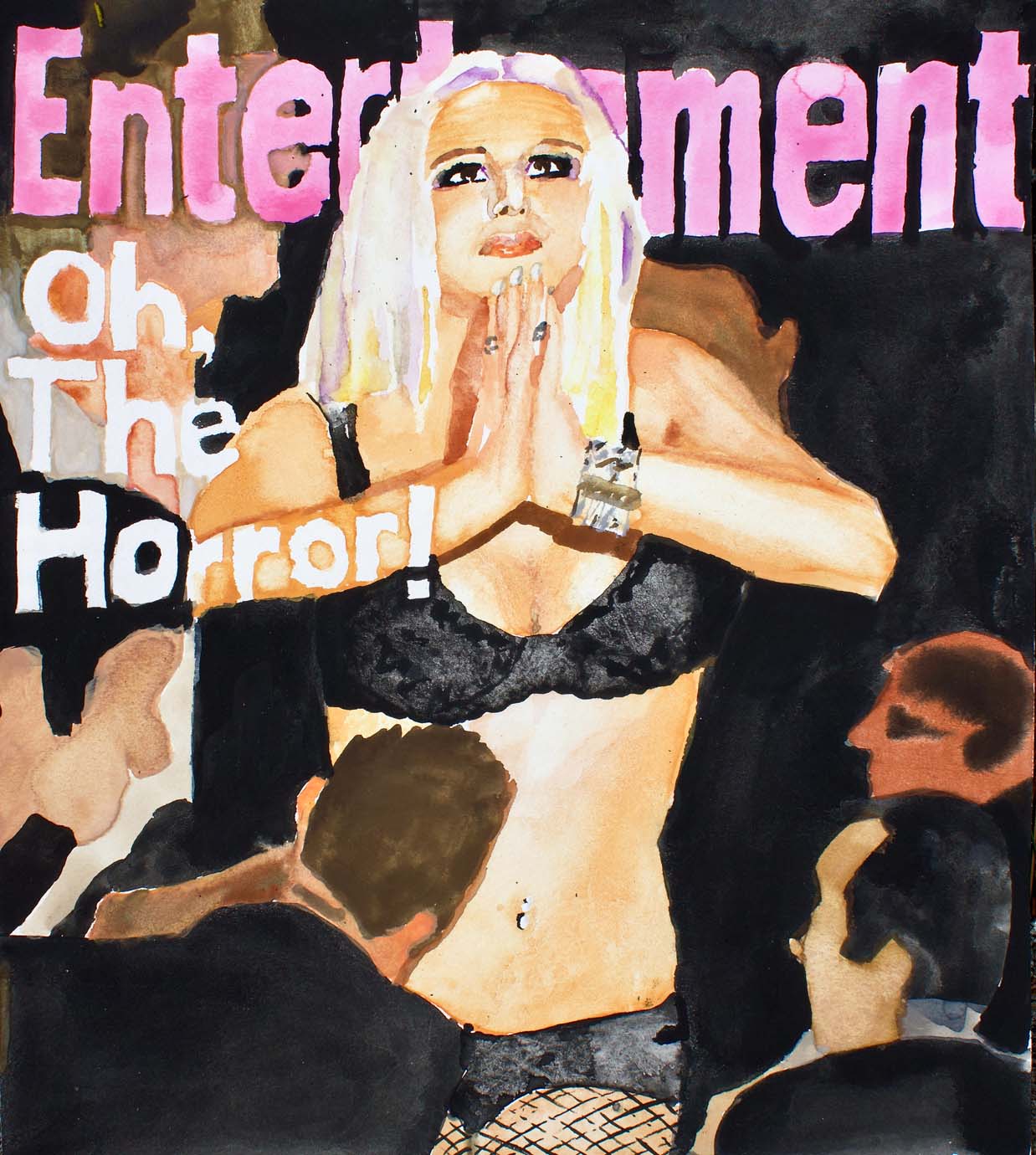

PB: Blackout could actually be read as an accelerationist manifesto of sorts. “Gimme More,” the lead single from the album, is, among other things, about Britney’s own endless desires in late capitalism that can never be fulfilled. She turns this disturbing reality outward to the audience, telling them that they always want more from her and that she has no escape from the cycle of unfulfilled desires. To understand how she ended up falling over while performing this death-drive anthem at the 2007 VMAs—one of her most iconic moments—we need to look at her formation as an American subject.

Born on December 2, 1981, Britney grew up under President Reagan’s economic policies: austerity for the poor and unrestricted free market activity for the rich, sold under the deceptive banner of prosperity for all. These policies unleashed the dramatic wealth gap that exists today, with the white billionaire class benefiting at the expense of the working class, especially poor BIPOC communities. Britney’s formative years were spent in a marketplace flooded with fast food, fast fashion, manufactured homes and all other things built not to last: disposable goods made for disposable workers. At the same time, her life was shaped by the belief that riches and fame were within reach.

Rich and famous since 1999, Britney has steadfastly remained a trendsetter in everything lowbrow for two decades. She has unapologetically basic taste, an all-around Kmart sensibility. She helped popularize the lower back tattoo, otherwise known as the “tramp stamp.” Grocery shopping lists leaked a few years ago revealed Britney’s penchant for Wonder Bread, Velveeta, SpaghettiOs and Red Bull. In 2004, her bridal party wore hot pink velour tracksuits for her wedding to backup dancer Kevin Federline. For that decision and many more like it, she has been mercilessly ridiculed. Yet, if America had a cultural attaché, Britney would be an ideal candidate because of the unique way in which she is an ambassador for the (white) American dream in all its discontents.

Britney’s aesthetic emerges from growing up poor in the Bible Belt, in Kentwood, Louisiana (population 2,419). Her dad ran a homemade gym in a repurposed barn, where she worked as an aerobics coordinator beginning at age twelve. Britney’s formal education ended in the ninth grade. The Spears family put all of their limited resources into Britney’s early dance and vocal training, which led her to the Mickey Mouse Club, the first stop on her road to stardom. In a 1992 MMC feature, she was interviewed in her great-grandmother’s seafood deli; later, on Primetime Live in 2004, she talked about being afraid to fail in life and go back to selling crawfish, while at the same time reminiscing about the simplicity of her childhood, telling Diane Sawyer it was “very nice.”

I can draw parallels between Britney’s childhood and my own. I also grew up in a white working-class family in a small American town. My relatives are in the fishing industry and my mom runs a seafood market. I also grew up onstage and my parents had very little money. They paid my dance teacher with clams and salmon. I started ballet at age five and from that point forward was constantly performing in dance productions and beauty pageants. I am familiar with the psychological dimensions of an existence in which the value of your person is placed on your performance. Alongside fleeting victories, there is enormous pressure and crushing disappointment. That existence can be vapid and simultaneously have so much depth within the heart of the individual experiencing it. The desire to be somebody, to be more than the seeming nothingness of the small town that you came from, is all-encompassing and will, in most cases, destroy you. The high-risk, high-reward capitalist model is unforgiving.

CG: There’s a lot to unpack when we think of Britney as both a consumer and an object of consumption. Maybe the same thing could be said of any celebrity, but with Britney there is a particular maximalist American consumer aesthetic that has been such a big part of her identity (Uggs and Juicy Couture, Starbucks and 7/11). “Outrageous, my shopping spree,” she bragged on the track “Outrageous” in 2003. It’s probably worth mentioning that much of Britney’s fortune comes not from record sales but from her perfume line, which has released nearly thirty fragrances since 2004, including “Believe,” “Prerogative Rave,” and “Sunset Fantasy.”

No other pop star has been quite as ingrained in the world of American consumer culture, whether it’s teenage Britney on her L’Oréal-sponsored “Hair Zone Mall Tour” or twenty-something Britney driving aimlessly around southern California, stopping for Marlboro Menthols and drive-thru Frappuccinos. The recently-launched The Zone: Britney Spears, which is marketed as an “immersive retail experience,” actually occupies an abandoned Kmart in LA. (This big box initiative was organized by two Britney superfans in collaboration with Spears herself.) There’s this feeling that Britney is America, and that she embodies the actual texture of the American shopping landscape in a singular way, even as that landscape decays into irrelevance.

PB: What happens in The Zone? What is this otherworldly retail experience? “The Zone” is also the name of a mystical site in the 1979 sci-fi film Stalker by Andrei Tarkovsky. To get to this other realm you can only be taken by the Stalker, which translates to “guide.” Today, Britney is our Stalker, the guide taking us into her Zone. We are on her Radar.

It’s interesting to situate Britney’s Zone within relational aesthetics and consider it alongside the evolving participatory pop-up museum world. The Museum of Illusions on 14th Street in Manhattan has a line wrapped around the block at all hours. With advertising slogans like “New York, the place to experience illusions,” I think they’re onto something. After all, how many lives in NYC are tethered to the illusion that “making it” is within reach? In reality, pizza is more within reach and the Pizza Museum was the biggest happening in Brooklyn the weekend it opened in 2019. Paid for by DiGiorno, it had product placement throughout and plenty of opportunities for selfies. It was a sales trap, known within the industry as a “marketing activation.”

Within a similar nexus, Tino Sehgal constructs museum experiences in which performers use a script to interact with guests. Unfortunately, when I experience a Sehgal piece, I feel like I just walked into Uniqlo and my subjectivity is being emptied out—what little I have left. My new companion takes me for a ride, performing sympathy under the guise of art-world pretense. Where does the ride go? Straight to the cash register.

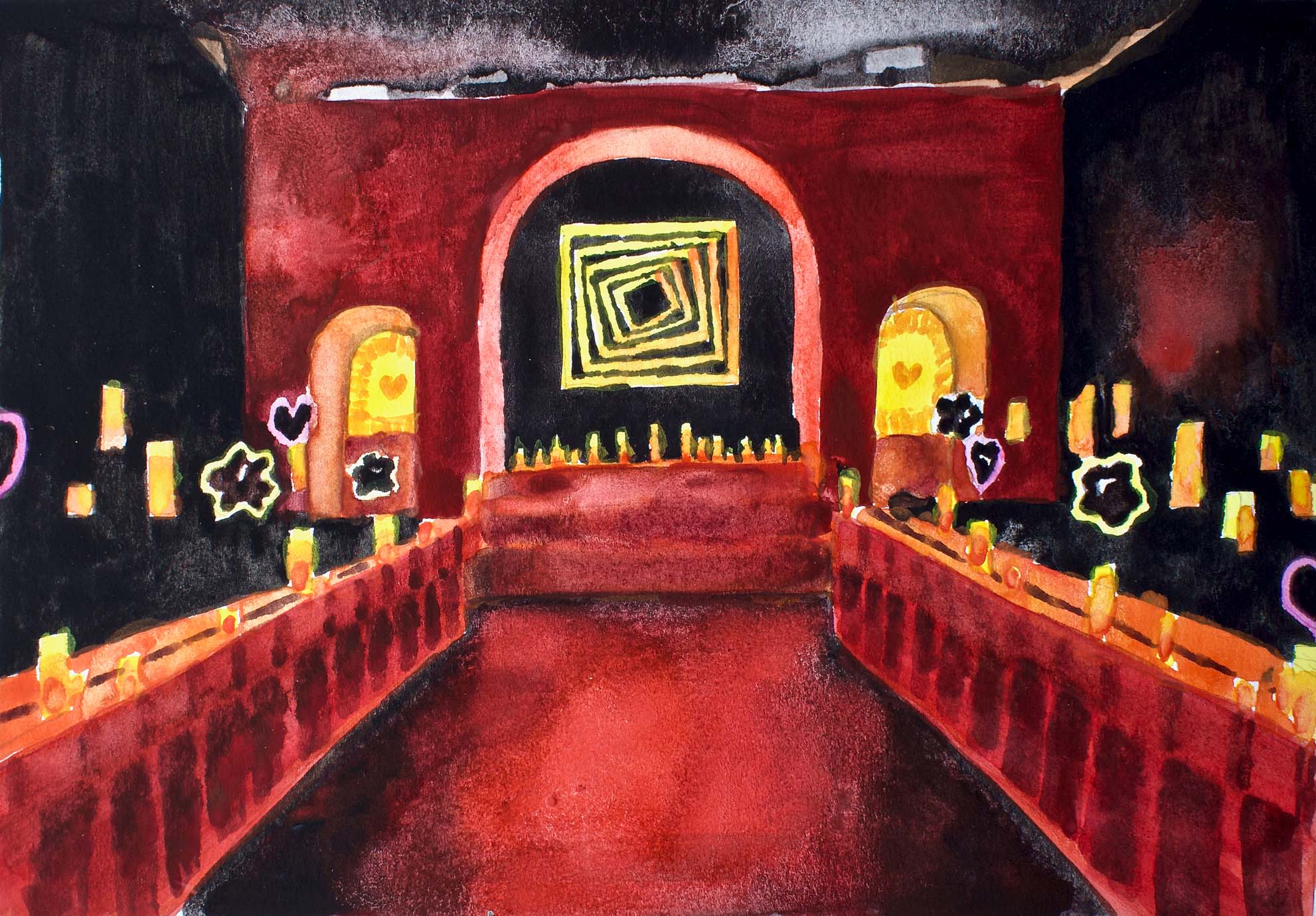

The Britney Spears Zone gives us more: nine interactive rooms with fully reconstructed set designs from Britney’s music videos where visitors are given the opportunity to perform reenactments of her works. To visit this abandoned Kmart is a pilgrimage. I imagine the experience to be ceremonial and full of rituals, like a séance: to enter into the choreography of Britney’s work, to dance until the world ends, to become Britney for one moment, in her absence. One of the rooms resembles a chapel with stained glass where fans might pray, whether to god or to Britney. (Britney is referred to as “Godney” by her fan base.)

CG: I love the way you interrogate relational aesthetics through the lens of consumerism, thinking about how the art world has been hollowed out by the market. Given the state of the art world, and our aim to position Britney as an artist, is The Zone any less legitimate as a cultural site than the Rothko Chapel? Might it be more relevant than The Shed? It is at least transparent in its presentation as a spiritual retail experience, priced at $59.50, with content that is designed to be reproduced on Instagram.

A visual analysis of the Blackout Room inside The Zone (the “chapel”) reveals something of a post-minimalist shrine, its neon palette and floating mirror fragments recalling works by Dan Flavin and Robert Smithson, albeit with a floral twist. The glowing yellow-on-black motif of spiraling squares within the altar would be at home in any museum’s postwar art collection. Taken from the Blackout album cover, this graphic reads as a portal, a time warp and a careening subversion of the grid, all at once. Moreover, the occupation of an empty Kmart is not unlike contemporary art installations set up in abandoned factory buildings—take Dia:Beacon and Mass MoCA, both sites transformed into art spaces after globalization emptied out the American manufacturing sector.

For now, COVID-19’s ruthless shuttering of brick-and-mortar businesses, which were already imperiled by online retail, enables Amazon and Facebook to loom ever larger in our lives. The parallel between Britney’s journey and retail blight is perhaps an even more compelling story than the conversion of industrial spaces into museums; she has followed American shopping down the drain like Orpheus following Eurydice into the underworld, and we enter The Zone almost like walking into a tomb. Britney offers a way to visualize the simultaneous collapse of capitalism and whiteness, these twin mythologies that have been so central to her story.

But it’s important to reconsider Britney’s class consciousness—emerging from a working-class background to become a troubled embodiment of the American dream and, now, the arbiter of the incredible Mimi Zhu re-post, and maybe even… a Marxist? I’m thinking of the discussion in recent years about the political destiny of white working-class voters, who are largely experiencing diminishing fortunes in late-capitalist America. We’ve all read about how the American dream is dead, or at least slipping out of reach for the vast majority of people. It’s incredibly seductive to imagine that this is where Britney has arrived as she approaches forty: exhausted by the American dream and the ways in which it has impacted her life; on hiatus, reflecting on the forces that have led to her isolation; interested in the possibility of a radically different America (and maybe even a radicalized Britney) emerging from our current state of crisis. Her legal state of non-being is, in many ways, now our state too. Where might she lead us?