“It is incredibly important for Black and Brown TLGBQIA+ folks to be photographed, and to have a consensual and thoughtful space that promotes personal agency,” Texas Isaiah tells me over email on the eve of his birthday. When he photographs someone for the first time, he asks, “What is your relationship to photography?” and “How do you feel when you are being photographed?” These questions, he says, “open up a particular kind of space to explore how we can collectively create an image together.”

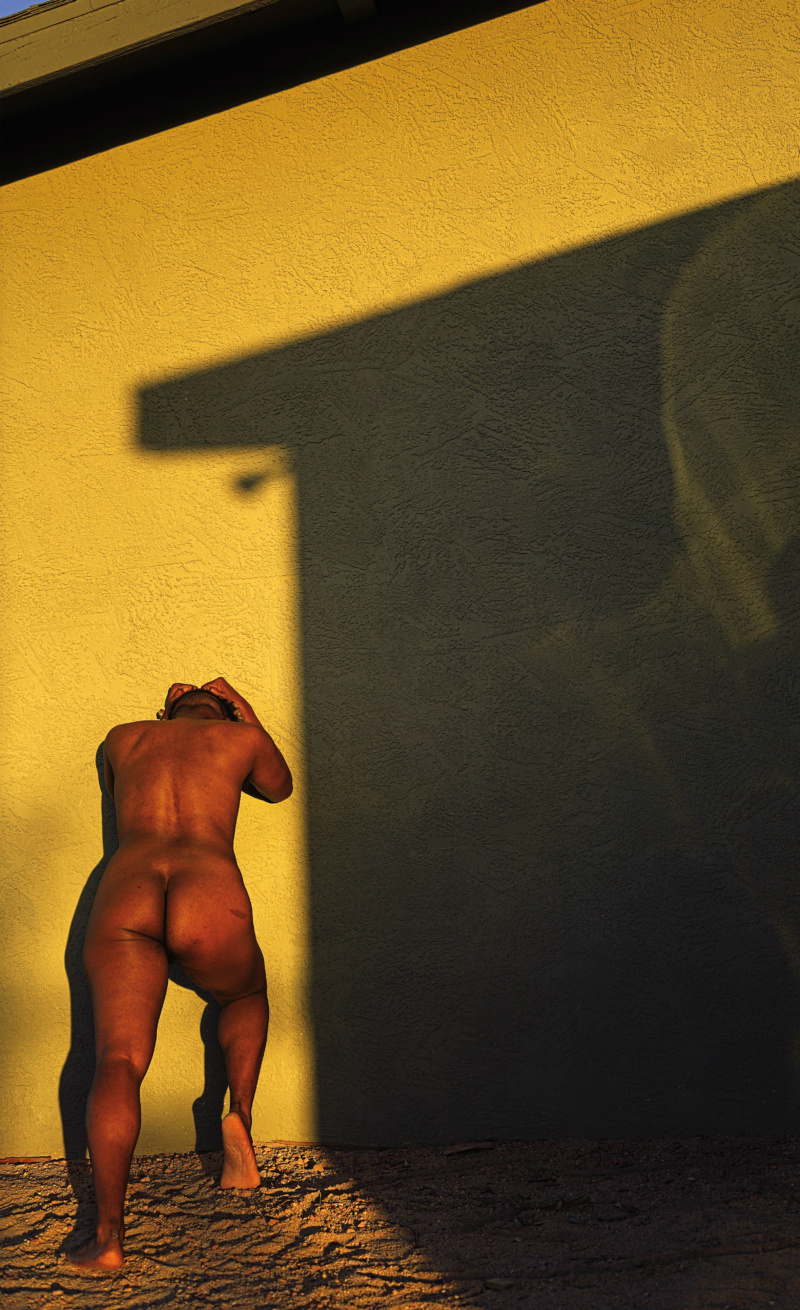

After moving from New York City to Los Angeles, Texas Isaiah began to ask himself these same questions. “I want to photograph my own body without repeating violent patterns,” he explains. “Some visual works are very anthropological, and my body isn’t here to be examined. That is why I lean towards using chiaroscuro within my work. The shadow protects me, and the light caresses me.”

Texas Isaiah photographed me a decade ago when he was shooting lots of young folks at parties between 2008 and 2012, after too many Manhattan punk venues closed down. “The dance floor was our safe haven,” he recalls. “I think about all the people I surrounded myself with and witnessed from afar, growing up. Folks who felt cemented and confined. An entire landscape of limited access to nutrition, education and opportunities. It is one of the many experiences that have led me to investigate how care, protection, legacy and intentionality can be processed through photography.” Texas Isaiah gravitated toward young black folks; “the conversations between us were effortless,” he says, “a soft space that neglected the gender binary. I found myself feeling like myself.”

That period would help cultivate Texas Isaiah’s understanding of topophilia, the loving bond that people can have for a place, a guiding lodestar for his practice. His first introduction to the concept was his upbringing in Brooklyn, within a family from Barbados, Guyana and Venezuela. “I am a first-generation Black indigenous individual,” he says. “I acknowledge the many homes my ancestors come from, however Brooklyn is the home I am most aware of in this body.” How safe and loved does a body feel, his images seem to ask, in relation to its surroundings? Drawing from his and his sitters’ relationship to the site, the work grows and transforms just like people do.

When Texas Isaiah honors his ancestors, he forms narratives about himself too. His recent photo series, my name is my name, “began as a conversation I was having with myself and my ancestors about the remnants of grief,” he explains. Texas Isaiah documented himself in a state of mourning, silently communicating with his ancestry. The project, displayed in a new incarnation earlier this year at We Buy Gold in Brooklyn, slowly grew into a public space. Composed of a vibrant altar he occupied daily, it was an exploration of both self-communion and the delicate place where private pain and communal transformation meet. “Where my name is my name i existed is in a space of mourning and grief,” he says, “my name is my name iii transformed into a healing space for myself, with the thoughts of the Black trans men who have found themselves experiencing copious amounts of erasure.”

With the project still ongoing, and a busy year behind him—showing in “The New Contemporaries Vol. 1” group show at Inglewood’s Residency Art Gallery, collaborative work with EJ Hill on view at the Hammer Museum as part of Hill’s inclusion in the “Made in L.A.” biennial and a talk at Art + Practice in Los Angeles—it would have been natural to ask what’s next, but I’m glad I didn’t. “I like to take things slowly,” he says. “We romanticize being ‘busy’ but we don’t often hold space for rest. I’m looking forward to feeling even more fulfilled, producing self-portraits that embody joy and the complexities and possibilities of what it can be like to love and be loved. I am thinking about the love between Black Trans people, specifically Black trans men/non-binary masc folks. I am always thinking about how to be better: a better person and visual narrator.”

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more

in your life?

in your life?