Few artists can improve on a masterstroke of minimal architecture—or would even dare to try. Philippe Petit, however, is one who can and this weekend, visitors to Philip Johnson’s Glass House will experience both creative forces, the architect and the aerialist, in tandem. Nearly six years after his initial visit to the historic Connecticut residence-museum, the high-wire performer plans to mark his 70th birthday with an intimate “Aerial Surprise” at the legendary modernist home. Completed in 1949, one of the first domestic designs of industrial materials like glass and steel, inspired by Mies van der Rohe, 2019 also marks the 70th anniversary of the Glass House.

“As Philippe likes to say, for 70 years, all guests to the Glass House have used the front door,” explains Glass House Deputy Director, Scott Drevnig. “But on June 8th, in honor of our 70 years and his, he will change that and make his entrance from the sky above.” Though Drevnig assures historians and postmodernist fans that while Petit’s performance will interact with the Glass House, the artist in no way alters the iconic site. “Preservation is always our priority,” Drevnig says. But the Glass House’s transparency and landscape resonates with those who may never have heard of Philip Johnson too. “You do not need to be a student of architecture to experience the minimalism, proportion, geometry and effects of reflection,” he adds. In fact, the estate also stewards a museum-quality 20th-century art collection, as well as Donald Judd’s first, site-specific concrete sculpture (Untitled, 1971), the last element to the property, acquired by Johnson in a trade for a Frank Stella painting.

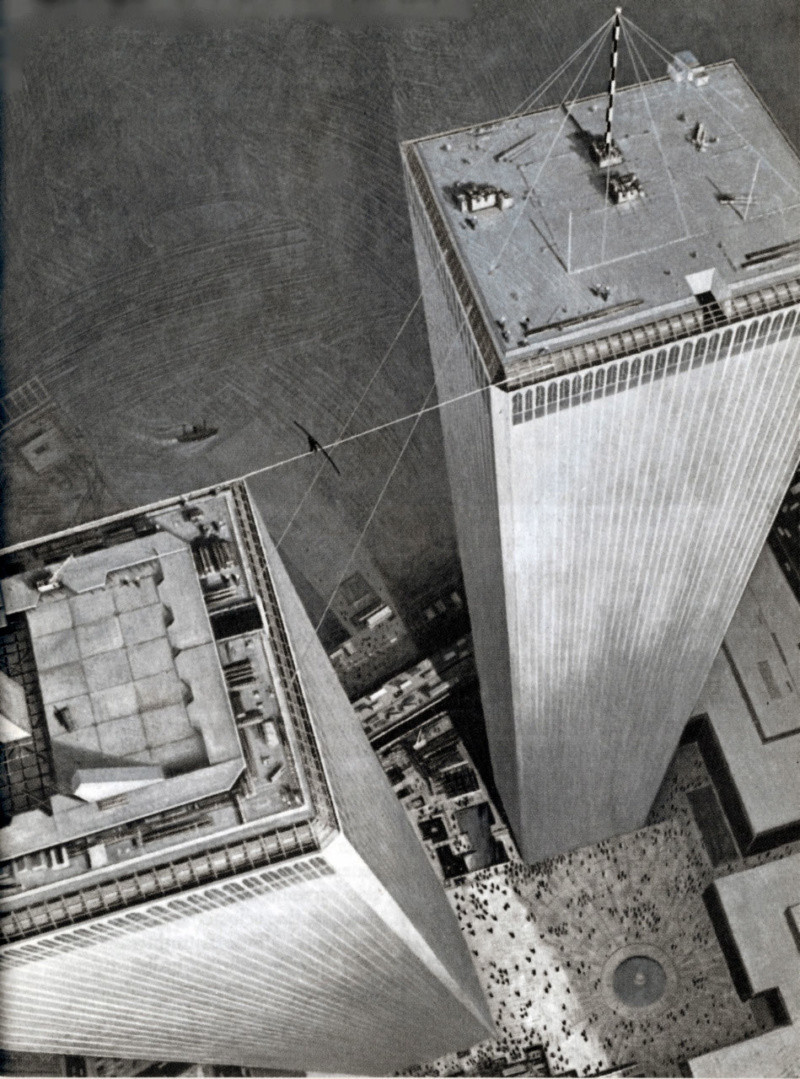

Petit is famous for taking his art to the celestial sphere. To much of the world, Petit will always be “the man who walked between the towers”—the hero of the beloved children’s book of the same name by Mordicai Gerstein, published in the wake of 9/11, later adapted to both film (2005) and a two-act ballet (2008). Every fall, Gerstein’s drawings and text become a kind of love letter New Yorkers invoke—as much to the World Trade Center, as to the Frenchman who danced across a tightrope he strung between the Twin Towers, on an August morning in 1974, the buildings’ last touches yet to be completed.

Suspended for 45 minutes, more than 1,300 feet in the air above lower Manhattan before surrendering to police, Philippe Petit’s Twin Towers triumph—in which he also lay, knelt and leapt back and forth along a cable ⅝ of an inch thick— is still one of New York City’s most daring, mythic displays of public art. The graceful, death-defying performance memorialized two iconic structures long before their tragic destruction. Yet, there is a strong undercurrent of fear that ripples through Petit’s work, for the artist surely, but also for the viewer, whose heart flickers: what if he falls?

Indeed, Petit’s practice is as much about activating architecture as it is a feat of engineering and choreography. In 1971, living in Paris, he first found fame for his illegal high-wire walk between the towers of Notre Dame—a performance now also with elevated poignancy after fire ravaged the hallowed French Gothic cathedral. A decade and a half later, he performed an authorized Eiffel Tower walk for the French Revolution Bicentennial. He’s also conquered St. John the Divine on the Upper West Side (arrested, upon completion, for trespass). “After learning by myself to walk on the wire at age 17, I was starting to look at places manmade and natural,” he says. “I started looking for magnificent, beautiful structures that will profit from having a cable there. I am fascinated by bridges, cathedrals, skyscrapers. But it could be a small building. Look at the Glass House.”

Forty-five years after he transformed New York’s skyline for nearly an hour, Petit’s audacity never ceases—imagining waterfalls, bridges, cathedrals, and skyscrapers he hopes to electrify one day. He stores these future ideas in a large box labeled Projects. “When you open the trunk, you see possibilities or dreams,” he says. “Things that will never happen because we’ll never get permission or will never get the money or whatever. Even the idea of walking on an iceberg, as the iceberg is floating away. I’ve seen this from films of course, like a Fellini movie.”

Always tailoring his work to the style of the architecture, Petit describes this weekend’s performance as an elegant high-wire apparition in three parts, including “a little surprise in the air in the middle about the birthday of the Glass House.” He plans rejoice for the audience, placing a 140-foot long inclined cable from a “beautiful little hill” in front of the house to its roof, with a program choreographed to Vivaldi, Telemann and Bach. “I cannot live without inspiring architecture around me,” he added. “I always associate it with my art.”