During a recent studio visit with legendary nonagenarian artist June Leaf, who emerged as part of the “Monster Roster” scene in Chicago in the 1950s, I shared my plans for the exhibition Painting is Painting’s Favorite Food: Art History as Muse, which opens tomorrow at Amalia Dayan and Adam Lindeman’s new gallery South Etna Montauk. Leaf and I spoke about her work’s relationship to the CoBrA movement in Europe. I had taken the title for my new exhibition from the art movement’s late charismatic founder Asger Jorn who loved what he dubbed “sofa paintings”—anonymous flea market canvases that he used as the supports for his Peintures Detournées. When I mused on how Jorn viewed art history as vital sustenance for his own work, Leaf interrupted and playfully compelled me to make my curatorial conceit succinct: “But what was the question you asked them?,” she demanded. “After all, curators have to ask artists a question when they invite them to be part of a show.”

“If we think of art history as a form of nutrition,” I proposed, “then the question is, ‘“What is your favorite dish?’” Leaf was bemused. After a long pause she glanced toward her bookshelf filled with monographs on the great historical masters. “There are so many great dishes,” she said.

If painting is indeed painting’s favorite food then this question could be asked of every artist. Looking at contemporary works of art, one can take great pleasure in decoding their answers. I have always been fascinated by the way artists look at other artists’ work. To this day, I still marvel at how art history is a vehicle for time travel, not only allowing us to see and experience the past but to witness how contemporary artists can reanimate–through Mary Shelley-esque alchemy–fragments of visual culture through their consumption, appropriation, quotation, homage or manipulation of art historical materials.

The exhibition at South Etna Montauk is part of a larger set of concerns I have explored for over 20 years, starting with research for the show Dear Painter, Paint Me that I curated at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 2002. At the time, I was querying the resurgence of figuration in the work of a then-new generation of artists like John Currin, Glenn Brown, Luc Tuymans, Elizabeth Peyton and thinking through the lineage of figurative painting coming out of the late work of French artist Francis Picabia, whose appropriation of pulp imagery from mass culture marked an antagonistic turn in the history of art that would have been impossible without his voracious visual appetite.

It’s no accident that Painting is Painting’s Favorite Food developed during these past months of confinement brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. With the shuttering of museums and galleries, the deprivation of real time experience looking at art in real life has heightened more than ever the essential role of historical art in the creative practices of artists and curators alike. If we accept Jorn’s thesis about art history, we could have made an exhibit that required the entire Metropolitan Museum of Art to accommodate a riotous cacophony of artists and their culinary tastes. Instead, our show fills a small Tudor-style cottage in the center of Montauk, New York with the work of 20 artists from varying generations and backgrounds. With several I enjoy ongoing dialogues, while others are people I’ve long admired and am collaborating with here for the first time.

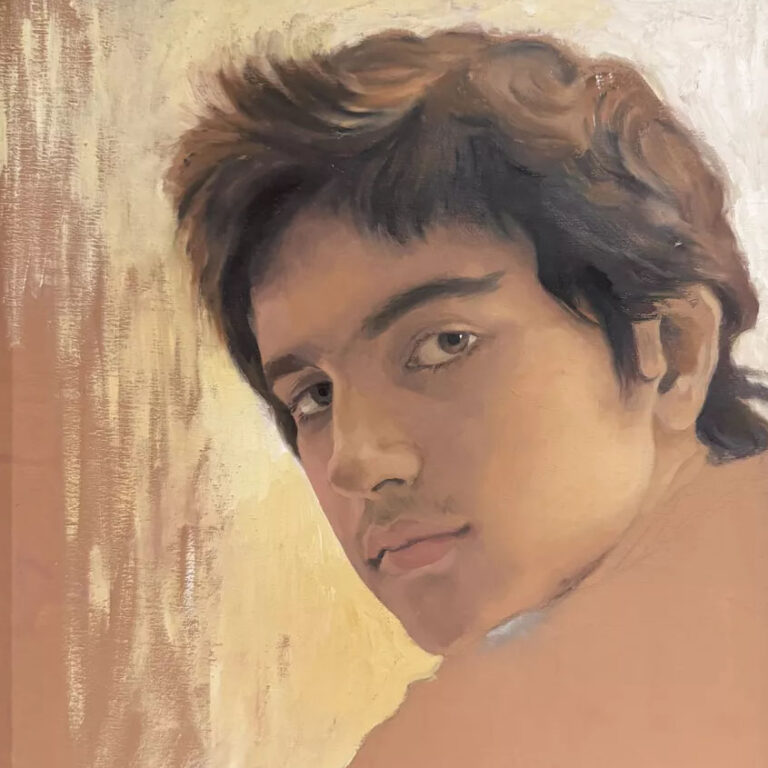

Among the artists in this show is Sam McKinniss. While I was working on Painting is Painting’s Favorite Food, he sent me a text with this passage by the art critic Edward Lucie-Smith writing on the late Henri Fantin-Latour:

…any enquiry into the qualities and defects possessed by Fantin as a painter must look first of all at the long years which he spent incarcerated in the Louvre. This incarceration was symbolic in two ways. It reflected Fantin’s feeling that painting was an occupation which fed upon itself, rather than upon experience imported from outside. … Both his choice of subject matter and his way of treating it tend to suggest that what is shown is only the ostensible, rather than the real and deep, motivation for creating the image. The real reason is the act itself, the act of picture-making. The Louvre had another function too. It served Fantin as a refuge.

Oh, to be locked down in the Louvre! Now that we are slowly regaining the possibility of having physical access to the trove of works in museums and galleries that we once took for granted, I hope this exhibition conveys how vital art history is to our visual and intellectual diet.

in your life?

in your life?