Pierre Davis grew up at the turn of millennium rocking sneakers, sweat suits and classic Tommy. But even as sportswear reigned supreme, she was equally intrigued by the femme glam staples in her mother’s and grandmother’s closets—plush furs, elaborate hats, and stacks of black hair and style magazines. She pored over these glossy pages, filling notebooks with sketches of the astoundingly intricate hair styles. This drafting practice soon led to her first clothing designs. By middle school she was trying her hand at cut and sew. In 2015, an undergrad fashion school project blossomed into her Los Angeles-based label No Sesso— Italian for “no gender.”

Now 28, Davis also came of age in lockstep with the internet and social media, and the accompanying, unfathomable changes in our perceptions of space, time, information and communication. Like many gleefully insubordinate millennial- owned brands, No Sesso is difficult to summarize. Its enchantingly peculiar clothes are unisex, unsized and tough to place within conventional garment classifications. The items resist the idea that there’s a right way or person to wear them. Almost all of the brand’s models are people of color and some are gender non-conforming or transgender.

Images for No Sesso’s latest collection (NS 2018-1) were staged against an inflatable silver plastic backdrop that calls to mind the set of a Hype Williams video. Garments include metallic coveralls cut like a Dickies work suit; a sheer, loosely-woven pastel shift flecked with glitter; and a boardwalk-style airbrushed tee in searing sunset hues that reads “BOSSY DEAL WITH IT” in fat bubble letters. Abstract, asymmetrical tailoring confronts logo-heavy sportswear staples. An array of reconstructed, hand- sewn, knitted and reconstructed pieces are made with athletic fabrics, denim and iridescent clubwear materials. The models wore Nikes (one of the brand’s sponsors): Monarchs (the almost two- decade-old, recently rediscovered normcore staple), as well this year’s best-selling VaporMax.

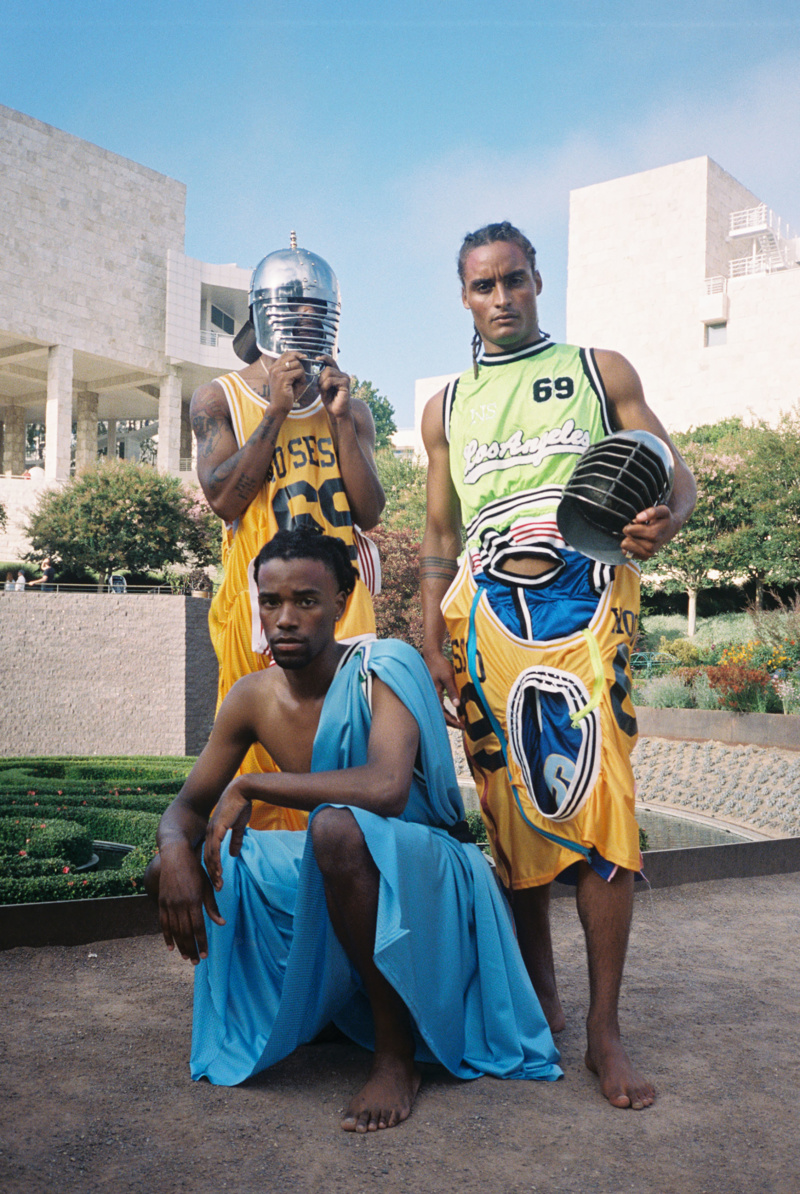

Despite an increasingly competitive market that is forcing the biggest fashion companies in the world to adapt (and fast!), young labels are hardly pressed. With drop releases now an industry standard, it is hardly surprising that Davis pays little attention to seasonal trends or buying cycles. And following streetwear’s lead, No Sesso and others align themselves with their local creative communities, often collaborating with other brands and multidisciplinary peers. Last spring, No Sesso partnered with LA-native avant-streetwear label Come Tees (founded in 2009 by Sonya Sombreuil, an art school alum with a painting degree) to produce “COMESESSO.” There were exuberant, hand-screenprinted dresses, two-piece sets, JNCO- style wide-leg jeans, a bucket hat, cloth earrings and a small backpack. Colorful graphics cheekily hijacked luxury house signatures, like Gucci’s GG diamond stitch and Versace’s thick banded stripes and block capitals. Lime green, blush pink and periwinkle were paired with a rich chocolate reminiscent of Louis Vuitton leather. Engaging the now-commonplace reflexive strategies of the logo flip and the bootleg, the collaboration produced one-of-a-kind craft objects while simultaneously pointing out that “authenticity” has become an all but meaningless category.

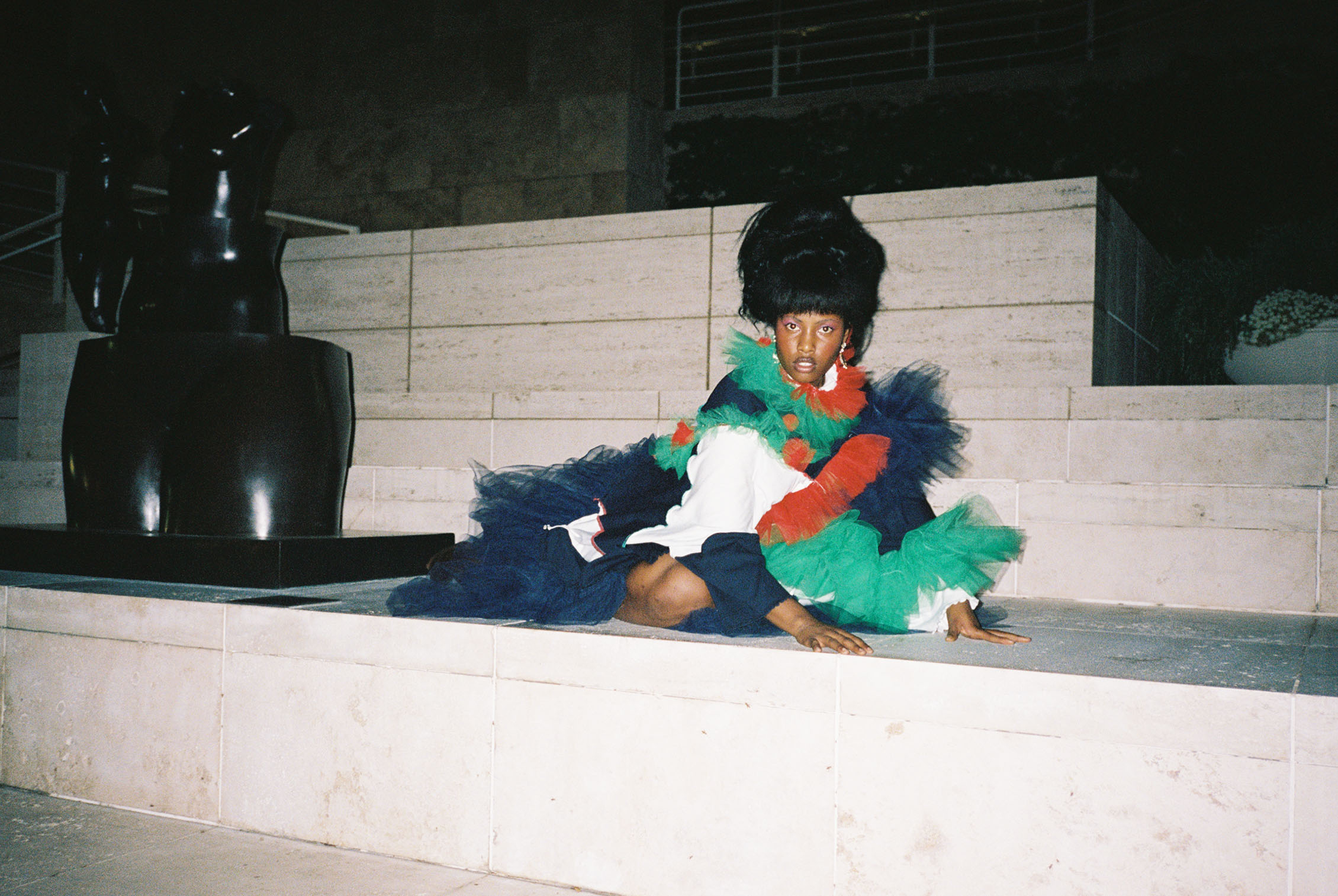

One might wonder if and how Davis will grow No Sesso’s prêt-à-porter, given the brand’s commitment to unique, labor- intensive handiwork. While the NS 2018-1 collection introduced a handful of sporty basics for sale in their e-shop, a jacket from 2016, completely covered with embroidered depictions of black women in various hairstyles and resplendent gold hoops, required six months to complete. Davis does not see No Sesso’s clothes as moveable inventory or even as haute couture, but rather, she told me on the phone, as “art objects that might someday be in a museum.” And indeed, No Sesso is already in these spaces and participating in such dialogues. In August, the brand was invited to hold a show at the Getty as the final installment of the museum’s summer evening series Friday Flights. Kelsey Lu scored the event and played cello on the runway. For the capsule, Davis took as reference points the ornate historical costumery depicted in the museum’s collection, re-contextualizing baroque extravagance within present-day concerns about resources and representation.

However, for fashion to become more like art, it must become, in some way, anti-fashion. Even the alleged merger of fashion and art—from artists walking runways to museums hosting contemporary fashion exhibitions—relies upon the same perceptual dichotomies that maintain them as mutually exclusive. Art has (at least in theory) always resisted creating exactly what fashion has relied on—a product that is both reproducible and scalable. And art’s value still requires that it remain antithetical to mass anything—mass production, mass culture, mass taste.

Slowly but surely, a changing of the guard is underway across these once dauntingly opaque and exclusive creative industries—and metrics of value and taste are shifting too. Among numerous intersecting catalysts, one is an awareness among young creatives like Davis about the limitations of traditional models of representation by and within elite cultural institutions and corporations alike. It has been clear for 20 years that prevailing iterations of identity politics were not subverting the fashion industry, but rather lending it content and credibility. Davis told me that she’s frustrated that representations of black, brown and non-cisgender people are often little more than marketing ploys—tactical moves for titillating an ever-widening and diversifying customer base. With a different kind of authenticity in mind, Davis and her peers are insisting on working with and designing for their own communities. They are redefining the terms of and the relationship between fashion, art and popular consumption. They are pushing and pulling at these precarious boundaries, exposing the fundamental instability of hierarchies of culture—of art/fashion and niche/mass. This means looking for alternatives—alternative ways of dressing, alternative communities, alternative measures of success.

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.