Karin Davie’s abstract paintings have a visual energy that any painter might envy, but their connection with a viewer is on a much deeper level. They communicate physically—corporeally—and then give you something to think about. Although, as Davie says in this interview, it would be misleading to consider her work conceptual, each of the successive bodies of work she’s made over the past thirty years has been very consciously conceived and constructed, and always with the play of meaning in mind. Her art constantly questions assumptions about beauty, pleasure and spectatorship in painting as a way of obliquely reflecting on their place in everyday life—especially as regards the body and gender. As was already apparent to me when I first wrote about Davie’s work back in 1993, her works “engage the politics of representation,” no less than its pleasures.

Born in Toronto, Canada, Davie had her first solo exhibitions—with Feature, Inc., in New York and the Jason Rubell Gallery in Miami Beach—in 1992. They immediately established her as a major presence on the painting scene in New York and nationally. But since her 2008 exhibition “Symptomania Paintings” at the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art in Ridgefield, Connecticut, her appearances have become much sparser as she’s had to deal with the debilitating effects of Lyme disease, which also led her to leave the East Coast for the Pacific Northwest. Her work has been very much missed. When I learned that she was preparing her first solo show in New York since 2007—at CHART through October 30)—I was eager to catch up with her.

Barry Schwabsky: Karin, it’s been fourteen long years since we’ve seen your work in any substantial way in New York. Yet the new work is instantly recognizable as yours—there’s an evident continuity, even though you are always experimenting. What’s changed in your view of painting, and what have you held fast to?

Karin Davie: What’s interesting is that it doesn’t feel nearly that long! I’ve had many challenges with Lyme disease over the past fourteen years, so that when I go into my studio, time slows down considerably. I think it might also have something to do with having moved from New York to Seattle. Not showing in New York these past years gave me the time and freedom to really experiment in my studio, something I cherish. I knew I was coming to an end with the series of work I had done in New York prior to moving. I had a sense that something else was stirring inside, and it was persistent. Of course, I didn’t know what it would look like but between 2008 and 2009 when I completed what turned out to be the last painting of the “Symptomania” series, I had already begun painting with smaller curving gestures.

This new work came out of looking back to some earlier work I had done in the 1990s. I seem to like looking for loose ends to pull at, which can bring about change. I like seeing if there’s something different that can be revealed from an older image. It’s similar to my interest in using almost ubiquitous popular images like the wave or stripe and trying to bring to the fore something that might have been suppressed by the cultural climate at the time. One thing I’ve learned about myself over the years is that I can’t make work unless there is something that feels like it’s one step ahead of me—an experience that’s surprising. It’s a bit ironic because I make repetitious and serial work. I’ve also had to make some practical adjustments. I changed my working methods and my painting mediums to be less toxic. These new paintings have had several incarnations. Originally, I was painting them all upright on the wall, but I wasn’t satisfied with the square ones, so I changed to painting them flat at waist height, something I had not experimented with since graduate school. But this change was significant. Two things that remain constants in my work are a need for repetition and a physical bodily gesture.

BS: The patterning in your work is optically hypnotic, like Op art, and yet the gestural energy and physicality of your mark-making reminds me of Abstract Expressionism—which is paradoxical, because those movements are supposed to be antithetical.

KD: Yes, I think there are lots of contradictions in my work. I like putting together opposites to create tension—such as between optical and physical, fixed and mutable, abandon and control. Although in a funny way, I think those two aspects you mention might share some common ground. Both Op art and Abstract Expressionism are movements I’m interested in and have a natural affinity with. They’re viewed as being on opposing sides of the art spectrum. But for me, they both seem driven to create an experience that revolves around energy and movement—optically and physically—and allow the viewer to participate in it.

In the vein of mind-body dualism, I like to think of the gesture in my work as a representation or record of the human body’s nervous system. To my mind, this is a weird combination of the two opposing movements. It takes a slightly distanced and skewed view of the traditional idea of gesture, and I love the idea of always being both inside and outside of myself. Although I don’t consider my work conceptual, I’m always thinking about the making of the work and my relationship to it as both the maker and viewer and how to deal with building that into the image without it becoming purely about process. It’s almost as if, with this new work specifically, there’s the part of me that is the creator and facilitator but also the obstacle: At times, my physical body and its limitations can get in the way. I like working that dualism and its potential for disruption. This is another example of contradiction in my work. As the song goes, “I’m a little bit country and a little bit rock and roll.” Well, I’m a little bit Ab Ex and a little bit Op.

BS: I’m intrigued by your idea of yourself as being an obstacle to your own work, but of the obstacle being paradoxically productive. Can you explain in a little more detail how that works in the new paintings?

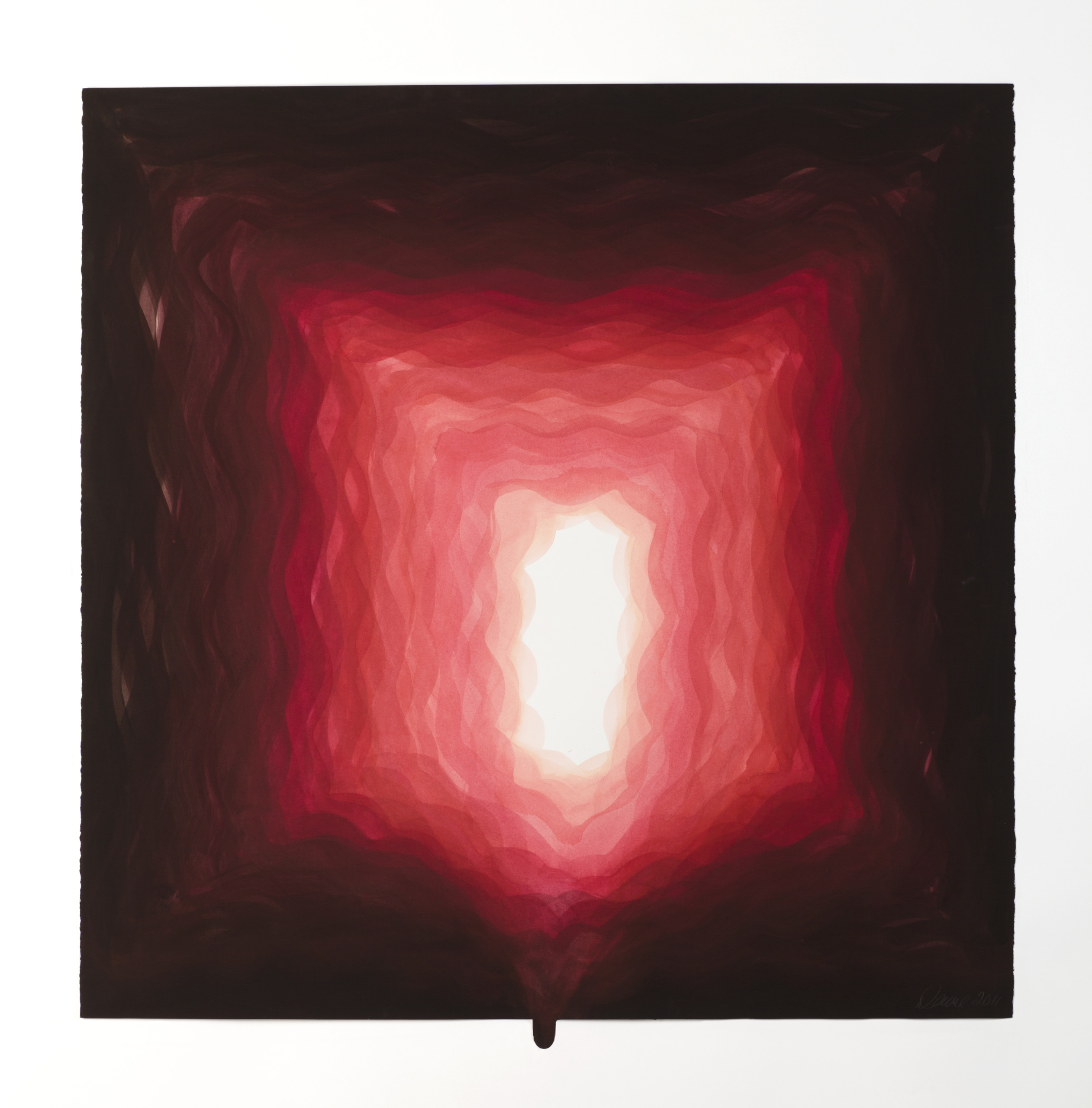

KD: Years ago, when I first started experimenting with ideas for this new work, I made some black gouache drawings with unbroken wavy lines around the inside edges of a square. I had done drawings like this back in the early 1990s. As I was painting the strokes around the edge on the floor, my other hand held the paper in place. But I struggled to get the form and rhythm of the undulations, because that hand was in the way. I had inadvertently interrupted the continuity of the waves and had literally become a part of the drawing. It was a bit frustrating, but funny and surprising at the same time. I liked seeing my body become a part of the image. This idea of using your body to set up an obstacle or create an interruption, getting in your own way, was compelling, so I decided to incorporate it into the drawing by cutting out the shape of my thumb on the bottom edge of the paper. I made it so that it pushed up into the image or pushed down off the bottom edge. The wavy strokes accommodate this altered shape.

It’s an idea that has a playful and slightly mischievous relationship to Frank Stella’s early shaped paintings and the work of dancer Trisha Brown, who in one of her works used the inside walls of a room like the frame of a canvas to move her body along, and perhaps to some of Bruce Nauman’s work. In these new paintings, I’m using body shapes to imply an intrusion and create pressure against the pictorial and illusory space, which at the same time reinforces the canvas as an object. It seemed like the perfect way to pervert traditional squares and rectangles and to use shaped canvases again.

BS: That “interruption” reminds me of Edvard Munch’s Self-Portrait During the Eye Disease, 1930, where he depicts the interruption in his field of vision. But his rendering of this idea was not funny or playful! When I look at your paintings, I always feel like you took pleasure in making them, even if or maybe just because it was a challenge.

KD: These paintings were hard-won on multiple levels. I love painting, and it can be thrilling and cathartic to manipulate paint and watch an image come into being, but it is hard work and I can’t say it’s all pleasure. I’m too intensely focused for that, and on a strictly physical level, the work is pretty strenuous. The connection you make to Munch’s Self-Portrait During the Eye Disease is interesting. I never thought about those specific paintings in relation to my own, but I do think there’s a link. I love how he marries his dark subject matter to a formal sophistication and inventiveness. Though my work is abstract, it feels representational and is filled with morphing images that sometimes combine the malevolent with the mischievous. If this is playful, it is playing with fire.

Craving more culture? Sign up to receive the Cultured newsletter, a biweekly guide to what’s new and what’s next in art, architecture, design and more.

in your life?

in your life?