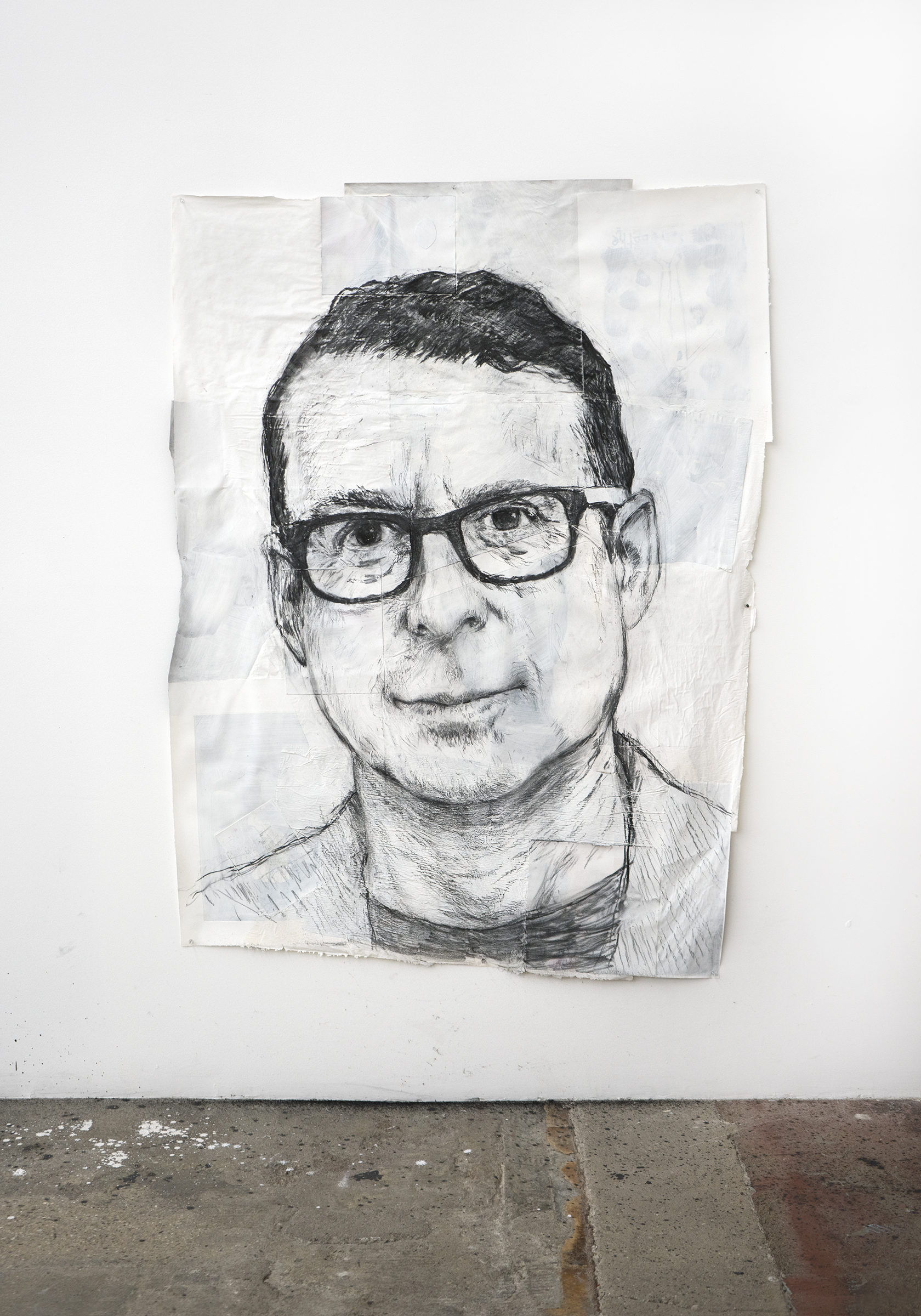

Despite the cold, dour gray of this January morning, the parking lot at the School is full for the opening of a retrospective devoted to the work of Andres Serrano. Gallerist Jack Shainman stands by the front door greeting locals and luminaries as if they’d all come for a potluck at his home. Among those admiring the photographs adorning the meticulously renovated, 30,000-square-foot space—which Shainman opened in a 1929 federal-style high school building in Kinderhook, New York, three years ago—are the dealer’s nonagenarian mother and his sister, Joan Zegras.

The family is close, and they often make the hour-long drive from Williamstown, Massachusetts, where Shainman grew up.

I ask his sister what she thinks of Jack’s success.

“I’m not surprised by it at all,” says Joan.

“He’s always had that eye for collecting, even when he was a kid. And his gallery is like a family—people are so loyal to Jack.”

My heart melts—into a puddle of despair.

As a journalist, what I look for in a dealer is a touch of evil and a hardness that when you scratch at it, sends off sparks. Because in an art business rife with such cunning and rapacious figures, those who inspire affection tend to play minor roles. Shainman is that rare animal who seems fundamentally good, is as gentle as a kitten and yet manages to feast with the jackals. Not that he’s out to join their pack. Although he operates two spaces in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood in addition to the School, he isn’t actively seeking out franchises in London, Hong Kong, Los Angeles or some other art world hub, like his peers in the highest echelons of art dealing. His sole ambition outside the city was establishing the School, which is close to Shainman’s weekend house—and close to his beloved horses. Shainman stands apart from his peers too, in having extra-artistic enthusiasms, in his case equestrian show jumping, a dangerous and difficult sport for which he spends hours each week training. In fact, he moved Upstate “in order to be outside more,” he says. “I love my horses so much, and I think if I didn’t have that I would have gone nuts by now.”

Nevertheless, his distaste for global domination does not mean Shainman can’t play the art game with the best of them. Even a cursory glance at his prestigious stable of artists indicates that he operates in an arena all his own, one that is notably inclusive and international. His roster includes artists like Kerry James Marshall, whose widely celebrated traveling retrospective, which just closed at the Met Breuer, was called a “breakthrough” heralding the establishment of “a new normal, in art and in the national consciousness” by The New Yorker; MacArthur “genius” grant winner Carrie Mae Weems; perennial fan favorite Nick Cave, whose work fills Mass MoCA until August; El Anatsui, winner the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the 56th Venice Biennale; and emerging stars such as Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, who will have a solo at the New Museum in April.

Whether wittingly or not, Shainman, along with his partner, Claude Simard (who died in 2014), worked to create the multi-hued multiculturalism that is the “new normal” of the art world since the very start of their careers. “They understood that there was something lacking in how other gallerists thought about what was going on in the contemporary art world,” says Weems.

If gallerists divide into two basic types, traders and collectors, Shainman is resolutely of the latter persuasion. Growing up near the Clark, a world-class museum at Williams College which he frequented as child, Shainman developed a love of religious, in particular Catholic, imagery. But Shainman, whose father was a professor of music, was not born with the kind of money that would allow him to acquire the 17th century Spanish paintings that you can now find propped against walls in the numerous storage rooms throughout the School.

By the time he graduated from American University in Washington, D.C., Shainman knew that he wanted to work in a gallery. However, before he could apply for jobs, he lost his admittedly terrible resumé (this was before the computer age). So he thought, “Fuck it, I’ll just open my own place.” After a brief, abortive attempt in Provincetown, Massachusetts—where he realized that people wanted street portraits, not fine art—and an instructive year running a gallery in Washington, D.C., he and Simard opened a space in New York’s East Village. It was 1986, and the hot ticket in galleries was American Neo-Expressionism and Neo-Geo. Shainman chose to introduce mid-career Europeans who had never shown in the city before, like German artist Isa Genzken and the Iranian-born, London-based Shirazeh Houshiary.

In 1992, Shainman spotted a postcard of a young artist’s work on the wall of a curator’s office in Ohio. He spent months sleuthing out Kerry James Marshall’s whereabouts, and then finally persuaded the reluctant artist to let him mount a show. It contained a work, Plunge, depicting a woman on a diving board, which was about “plunging into the art world,” says Shainman. It sold for $2.1 million at auction last year.

“I’ve learned so much from Kerry,” says Shainman. “His work is all about the non-representation of black people in our culture, and so he wanted his paintings to hang in museums. He also wanted me to sell them to black collectors. In the early nineties, there weren’t a lot of black collectors, but it was really good to think about.”

Through Marshall, Shainman, whose roster of artists would become arguably the most diverse in the world, eventually came to work with the artist’s close friend, Weems. “Jack and Claude were clearly aware that there was a severe lack of representation of African-American artists, Asian artists—brown people—in the field,” says Weems. “And they were dedicated to acting as a corrective to that. They took a chance, and they won.”

Shainman himself doesn’t see his past in such a starkly political light. “I’m always looking for something that’s really new and not seen before, which is hard,” he says. He follows his passion rather than worrying about market viability. He recounts the excitement he felt upon seeing pictures sent back from Delhi by Simard, an India-phile, of work by a then-young artist Subodh Gupta. “I was like, ‘My God!’” says Shainman. “Nobody had seen stuff like that.” He began representing Gupta, despite the uncertain economics of doing so. “His works were selling for up to about $25,000, but of that, about half went to fabrication, and then we’re not even talking crating and shipping. I worried, would anyone spend $25,000 on an unknown artist?” says Shainman. “But we loved it.”

Of course, Gupta became an instant sensation, and was with the gallery for three years before decamping for Hauser & Wirth.

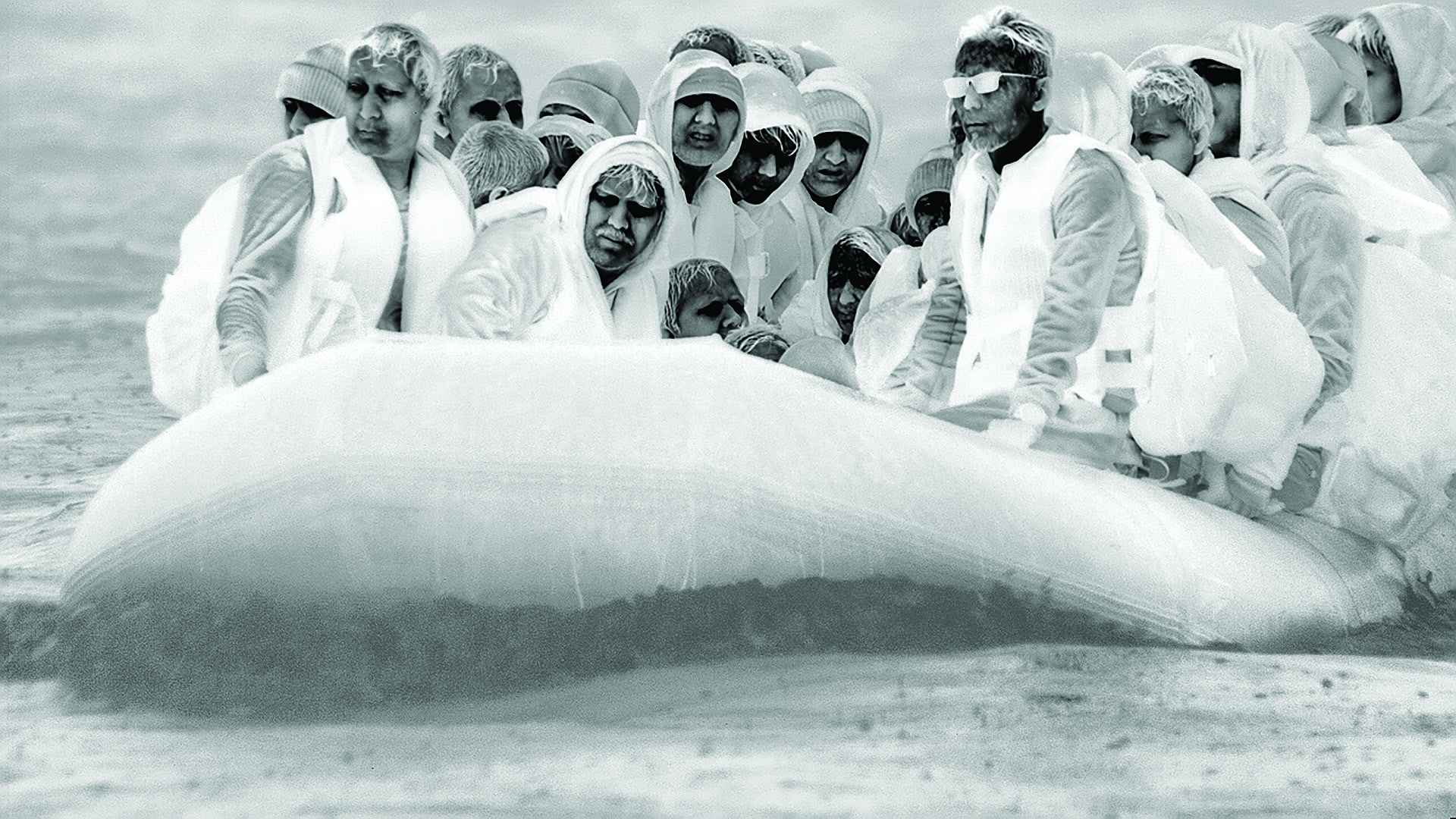

The newness they were seeking was relevance. “Artists who were dealing with issues that were global even though the work was about their lives. It’s the same with Yoan Capote,” Shainman says of the Cuban artist whose exhibition “Palangre” is on view at the 24th Street Chelsea gallery until March 11. “His work is inherently about being Cuban, being from that island, people leaving, but it resonates so much with Jews, with Catholics—the themes are universal in his work.”

Although the art world has finally caught up to Shainman’s global vision, it has been an arduous road. For a long time, he couldn’t get into a certain major European art fair. “I understood it was because of my roster of artists—it was too diverse,” he says. “It was really racism at the highest level.” Eventually he asked the director what was going on, only to be told, condescendingly, that he was “almost there”—this was in a year that Shainman had five artists included in the Venice Biennale. Shainman recounts this story without a trace of bitterness, as we walk through Kinderhook to pick up lunch. He seems genuinely uncontaminated by the need to jockey for power, prestige or even the normal perks of owning a large business. For instance, he refused to let one of his staff members pick up lunch for us and even insisted on calling to place the order himself.

That attitude certainly extends to how he conducts art business. Enrique Martínez Celaya, whose second exhibition with the gallery will open in March, points out that Shainman is “very good about paying artists. He’s also excellent at attracting important people to the work”—meaning taste-making curators and collectors—“yet at the same time I never see him hustling. He’s such a champion of the work that when he tells collectors about it, what they see is the excitement rather than the sales pitch.”

Shainman’s excitement in his artists has lifted him to a unique position in the gallery landscape, reshaping it in the process. As for what he discovers next from that vantage, the thrill will surely be ours.