For the past four years, artists Melanie Crean, Sable Elyse Smith and Shaun Leonardo have been working with a group of people between the ages of 16 and 25 who somehow found themselves entangled in the court system. Rather than face the typical punitive measures, these young people were directed by the courts to the non-profit art residency Recess for an eight-week alternative to incarceration program. From this starting point of arrest and prison, the group has collectively built one of the most powerful social practices within contemporary art—developing a performance-based pedagogical curriculum while simultaneously creating the film Mirror/Echo/Tilt. Inspired by Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote and made within decommissioned prisons and court houses in New York, Mirror/Echo/Tilt opened at the New Museum earlier this week. Crean and Leonardo spoke with Cultured about the language of criminality, non-narrative storytelling and the potential for re-invention within the body. How did you three come to know each other and work together on this project?

Melanie Crean: In 2014 when Mike Brown was killed, I was reading the book Don Quixote. There were parallels between how both the character and the author were defamed in the book, and how Mike Brown was criminalized in the press. You can see how society has long used media for social control and though it continues to reinvent its methods, it does so in startlingly familiar ways. I was discussing this with Sable, who brought Shaun into the conversation, and we talked about how we could address this in a way that is critical but also speaks to the potential for change. We knew we were interested to use methods related to embodied storytelling, which we had all worked with previously. We formed a partnership with the arts organization called The Point in the South Bronx, to work with a group of participants there who had been affected by incarceration in different ways.

Shaun Leonardo: When Melanie and Sable presented the broad strokes of the idea, I was deeply invested in my I Can’t Breathepiece, which concerns the killing of Eric Garner. I was moving through contexts both in and outside the artworld, working with different communities, and through that practice really started to think of the possibility of destabilizing how we position ourselves in the face of, let’s say, the video of Eric Garner’s death, and the ways in which, through a bodily practice, we might move individuals closer to the humanity of someone like Eric Garner, rather than distancing ourselves from the headline or the visual footage that is provided. So when they reached out to me about potentially working with participants who have been impacted by incarceration, I was already thinking about the possibilities of my performance practice and jumped right in.

MC: In the book, the writer, who positions himself in the text as a character, and the figure of Don Quixote are both defamed in the press. This negative persona takes on its own life so that wherever Don Quixote goes, the bad reputation precedes him, until Don Quixote eventually runs into and confronts this Other. We were thinking about this, and how media portrayal affects people and their self-conception, and how they might recuperate and tell their own stories differently. How do you see the conceptions of power shifting within your work?

SL: One of the core organizing principles that has really moved us through this practice is removing language and the possibilities that opens up—and carefully reading and interpreting body language as an alternative narrative. If we were to move directly into words—words surrounding a traumatic event, the telling of that event might distance its listener. This is what we witness in media portrayals or the headline phenomenon that we’re engrossed in today. When you see the headline, it’s easier or maybe more natural to move away, to distance the impact of the story from oneself as a way to self-preserve. But when you read something through the body, when you ask the narrative to flow through the body, you can find a commonality. The person’s humanity is centered, and it’s in that emotive space that we start to move closer to something that would otherwise be difficult to absorb. How do you tell the story of arrest and incarceration? Often you don’t have the language to articulate that sort of experience. The risk in telling one’s narrative solely through language is that often we use the default language of criminality. It’s difficult to acquire the power to tell that narrative on your own terms. So we remove language in order to see what other type of bodily knowledge there is.

MC: A key theme throughout the project is the potential for change. The potential for reinvention. The potential to reimagine something that seems utterly fixed and unmovable. We’ve done research with psychologists and theater practitioners who have been using similar methodologies for a long time, and we started realizing that when you experience something traumatic, the physical feelings are stored in a different part of the brain than the conscious, narrative part. So using this body-based intervention is a way to almost repattern the body and re-associate the story with more positive physical sensations in a more positive environment. Reinvention within the body.

In terms of the movement and the bodily participation as a curriculum, how much do you coach the participants in terms of helping them figure out, within their own bodies, what that kind of communication looks like and how much of it is a more internal response to what they’re being asked?

SL: We didn’t have an output fully formed when we started gathering with the participants. As a starting point, we often just existed together in space. It was through that gathering that we discovered the limitations of language. With our research into various practices, we started to experiment with non-narrative exercises. But it wasn’t laid out into a curriculum until much later on—nearly the final year of the process. Once we received the invitation to move it into the diversion space and to enact that type of change, we started to consider what it might look like in lesson plan form.

One of the most palpable moments in my memory was when the group decided that they wanted to talk about the death of Michael Brown. It was through that conversation that individuals started connecting the tragedy to their own experiences. That evolved into a process where we would not move directly into any particular narrative or experience of incarceration or arrest, instead we would center a single word like desperation, isolation, anxiety, but also things like aspiration, joy, promise, escape. By centering a single word, we would organize ourselves around a feeling to see where it was we might locate humanity in stories that otherwise might only be told through sheer drama. It was in this sort of conversation-based exercise that we started to develop not only a criteria, but also a potential step-by-step process. So much of it was unpredictable, spontaneous, by chance, and entirely generated through conversation.

MC: After someone would tell a story about their experience, we would encourage them to think about a singular moment in the event that they could identify as the emotional core. It didn’t have to be the most dramatic moment, but a point they thought was at the root of whatever happened that could convey the heart of the experience. We asked people to try to represent that in a single, performative, physical gesture. The process of synthesizing what happened, of stripping it down to the emotional core, and discussing it—not only about their own experience, but in the stories of others as well, was key. That was central to the practice because once people were able to identify those moments, they got very good to dialing in and performing them.

SL: In a collaborative effort, we could understand the complexity with which we were capturing these stories. We would build out these scenes as a way to analyze the powers, circumstances and decisions that may have led to that moment. It became clear to us that there was an emotive core where the reclamation of a story took place because these pre-existing narratives of criminality rely on the removal of humanity. In order to uphold and solidify how and who we think is criminal, the subjective point of view needs to be removed so that we feel that only “bad” people are put away.

MC: Also, part of finding the emotional core is to find a moment that transcends the specifics of the story. So even if you might not be able to relate to the details, there was a transcendent quality of emotion that you could relate to. Are the participants of the diversion program all from Recess?

SL: Yes, from the beginning Recess has been the home of the Assembly Program, which is now nearly three years old. After our initial conversations with Allison Weisberg, Executive Director of Recess, we opened a space and developed a partnership with Brooklyn Justice Initiatives (BJI), all within two months. We approached it in very much the same manner that we did for the film project, which was jumping in and simply existing with individuals—the difference being that now there were quite high stakes involving a young person’s sentencing. These are young people, aged 16 to 25, who have been arrested for misdemeanor or low-level felony charges, and rather than have their case pursued in court, they are referred to us. During a four-week workshop cycle, we dive into this process of translating a person’s narrative into performative gestures as a way to carefully look at the stories. Afterwards, their cases can be closed and records sealed so that they avoid an adult record. Do you talk with the participants about this as an art practice?

SL: There are two parts to this answer. At Assembly, it’s unimportant to me to frame this as art. That word is rarely mentioned. The participants understand that we are present within an art space, and of course there are artists and artwork surrounding us when we enact the performance curriculum, but I don’t approach it through detailing what we’re doing as a model for art. These young people are coming into this space with all sorts of expectations around what art might be, that is if they even know it’s an art space. Instead, the first motive is to create a distinction between us and the court system, and to establish a trust and a working energy that is about what might happen collaboratively in the space. What I center more than anything else is that as material, we are using their stories and that this will be about storytelling. But in terms of the film project, we do hold something in front of us that we identify as art.

MC: I make no practical distinction between between art and design and any other sort of creative expression. I don’t think most of the people we were working with did either. We used words like performance and film because we have to communicate what we’re doing, but it’s usually easier to demonstrate and experience this than to describe it. The first time we meet with a group, we sometimes do an exercise where we have two people shake hands in the middle of the space and freeze in that position. We ask everyone else to walk around and at first describe exactly what they see, without interpretation, to really pay attention to detail of what the body can convey. Then we ask who they think the two people might be, what is their relation, who has power. Then we bring in context. If they imagine the two people were on the street, who might they be? Or in a school, or in a court room? Through doing it, people start to understand how performance-based practices can uncover meaning. It’s better experienced than explained.

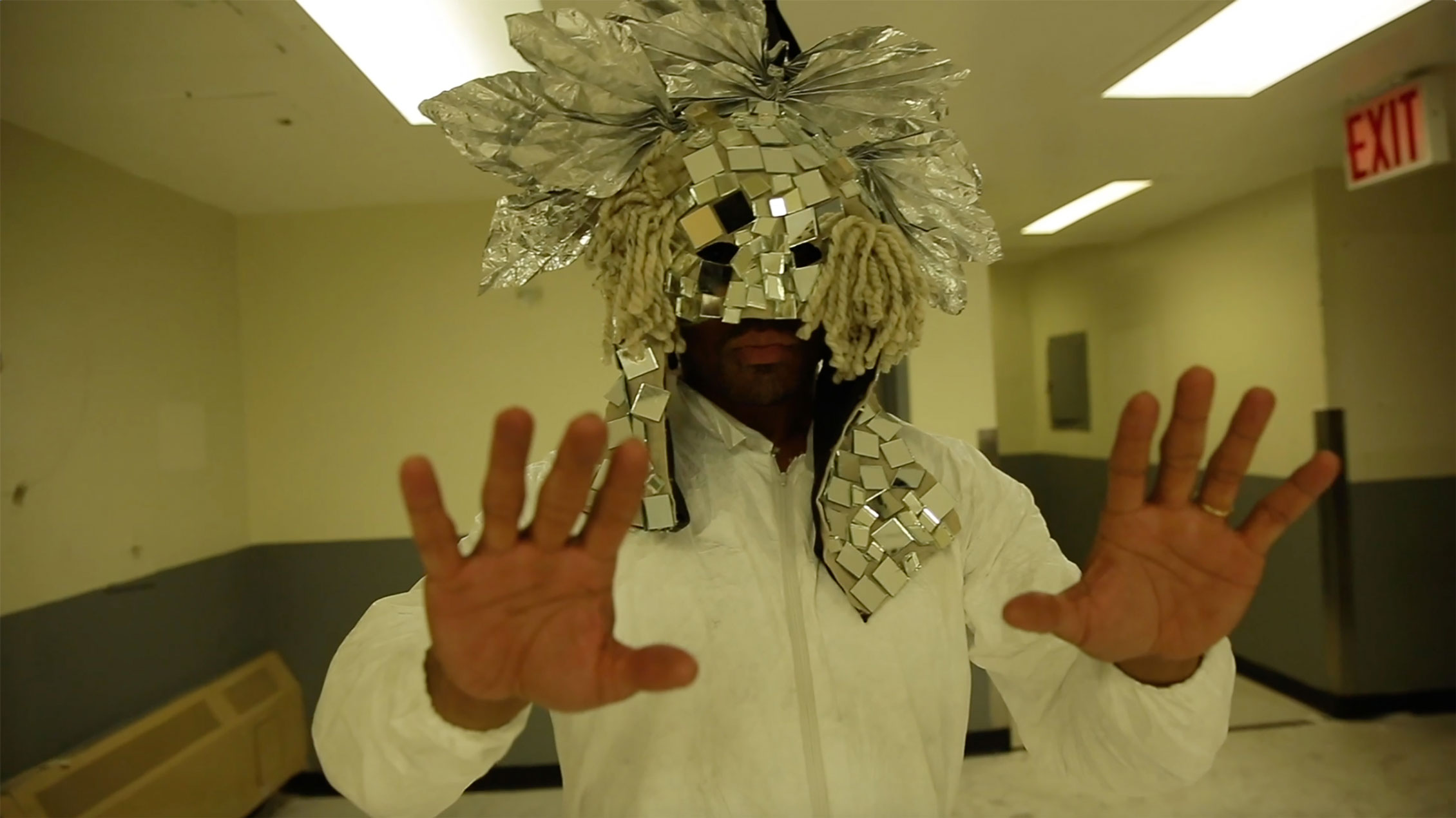

What is the role of the masks that are work in the film?

SL: One of the starting points of Don Quixoteis a character known as the Knight of the Mirrors, and this idea became central to our formation of subjectivity in the film. The Knight of the Mirrors comes late in the narrative of Don Quixote. He is the adversary that reflects Don Quixote’s own image back to him, and in that distortion shows Don Quixote his own madness. He is also the figure who claims to have defeated Don Quixote even before meeting him. So it’s in the poetics of the mirroring that we started to arrive at this strategy of “Mirror Echo Tilt,” and it’s in that philosophical space that we started to critically understand the role of the film through the lens of criminality—asking how we defeat that narrative. How can I reclaim the agency of my own narrative? That became the starting point. As an aesthetic of magical realism, it was a also device that helped us delve into difficult territory.

MC: The artist who designed the masks is Joanne Petit-Frere, who makes incredible wearable sculpture. There was one for the figure of Don Quixote and the Knight of the Mirrors, who had the most elaborate mask, and then for a group of people who were the Watchers, kind of a composite of a Greek Chorus and society at large. There’s also this complication of ideas of reality and fiction. Can you talk about that?

MC: I’m interested in the idea of a third space, or other spaces, heterotopias. These spaces where the normal rules of society do not apply. On the one hand, the reality of these spaces—decommissioned prisons and court houses—could not be ignored. There was unbelievable signage in the prison and all kinds of artifacts that very much made sure you knew where you were. Yet, when we were there filming in the spaces, it really felt like we were making gestures toward reclaiming them, and possibly tilting them towards this new identity. I think of it as a sort of suspended realism, like the suspended sense of reality where you’re somewhere outside of normal space and time. You’re very much informed by what you can’t escape which is all around you, and yet you’re in this transcendental space in the middle, in this membrane where you can make things happen. It’s somewhere in between. This idea informed the whole mise-en-scéne, everything you could see in the film, the way people are moving, what they’re wearing, the way that you can see people wearing bright white Tyvek suits, but over Nikes. It’s very much of our world, but apart.

SL: It’s in that slight fantastical shift where you more intently start to read the body. If it were to look entirely familiar or toward the depiction of prison as the media would capture it, then you would be locked into the space. But we were much more interested in this in-between.

MC: We talked a lot about this idea of Making Strange, about the distancing effect, and fostering a sense of objectivity with the performance, as part of reclaiming the narrative. If you decenter something just a little bit, sometimes you can more easily recognize it, and start to analyze things anew.

SL: The goal is not to center prisons. We do not want incarceration to be the first or last thing on everyone’s minds when they enter the space. It’s through the shift of that reality and the connection that might happen with individuals in the video that we’re hoping for a different kind of resonance.