“When you finish your masters, it feels like either you need to launch your line or go in-house at a good brand,” fashion designer Erika Maish tells me. “The pandemic in some ways relieved some of my doubt, because as friends began losing jobs in waves, I no longer felt like I should be applying to a big fashion house.” Graduating from Central Saint Martins in 2019, Maish planned to keep her eponymous brand London based, but while renewing her work visa and completing an order for Opening Ceremony, the outbreak of COVID-19 stranded her in her hometown of Los Angeles. She considers her current studio, the dining room of her art conservator parents’ home, a mixed blessing. On one hand, the temporary reprieve from rent has enabled Maish to focus on designing challenging garments and building out a clientele who respects her boundaries and believes in quality over quantity. But on the other side, the unexpected sojourn forced the designer to look at her own discomfort with the kind of Valley Girl aesthetic that Kim Kardashian piloted in the early 2000s and from which Maish has never quite recovered.

“Normally for research, I would be going out a lot more on road trips to flea markets, museums,” Maish tells me. “But being indoors, it's been movies.” She namedrops Tim Burton, Paul Thomas Anderson, Real Housewives of Beverly Hills, The Jetsons, and Larry Sultan’s television-ready photographs. Falling like Alice down a rabbit hole of old and new, the designer arrived at 1980s Los Angeles legend Angelyne, one of the first people to be famous for its own sake. Angelyne, with her mysterious origins and precipitous rise, became an important avatar for Maish. “Angelyne was just a person who put herself on billboards, changed her appearance and identity and then became a big personality in the city. Not much is known about her except that she is from the Valley,” the designer says. “I decided to put myself in a pink dress and photoshop myself on billboard to acknowledge her and to play with my own identity.” The project informed Maish’s entire SS21 collection, Tales of a Valley Girl, which was fittingly documented in her backyard on a green screen. “It was really liberating to create on my own terms,” she says of the experience. “As a pale redhead I never fit the mold. The video touches on stereotypes of the Valley but also offers my own take.”

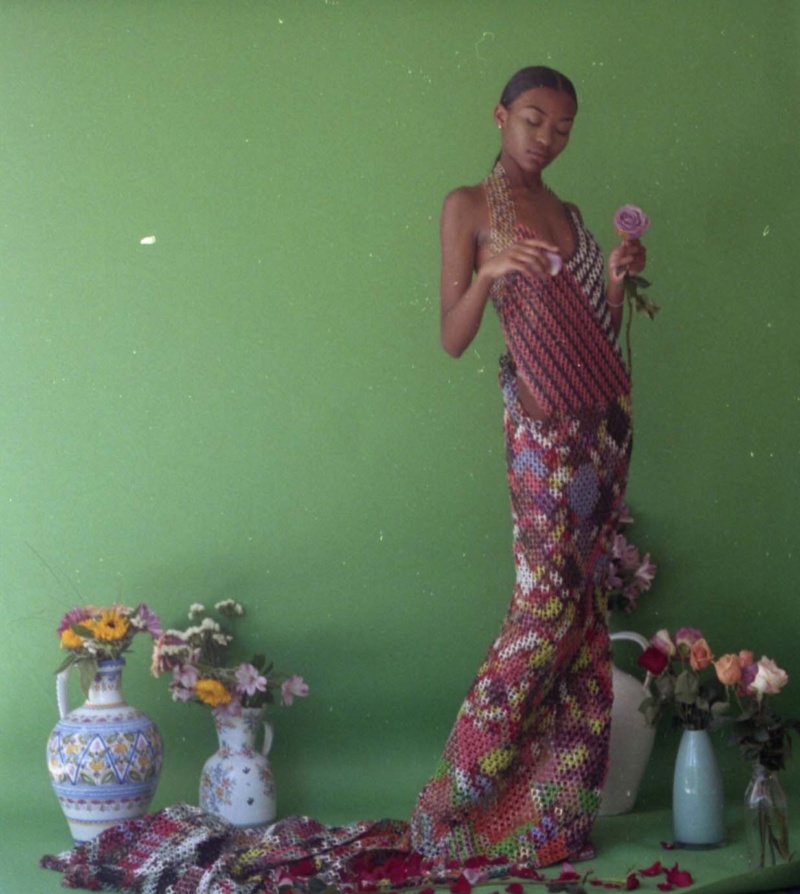

Maish’s assessment is not exactly flattering but it's not a scathing critique either. Tales of a Valley Girl centers around an intergenerational cast of women, all friends of the designer, enthusiastically acting out vignettes of domesticity in vibrant optical body-hugging knits. Wielding the vocabulary of stereotype against itself, Maish’s montage of exuberant models pushes back against the apathetic gum-popper and refocuses our attention on how demandingly creative and time-consuming feminine labor actually is. “The models are performing tasks associated with women's labor, and the techniques used in the clothes also express this,” she says. “My work is something that is very craft oriented and handmade. Just like domestic tasks normally performed by women, craft techniques like crochet aren't given enough value in society.”

The craft that ultimately gets Maish going is textile design although her materials are atypical to her chosen medium. The designer frequently challenges herself to construct knitwear with non-fabric materials, like the wooden beads from car seat covers and healing crystals. This means that when making a work Maish rarely finds herself over the sewing machine, more likely wrestling with pliers and industrial tools. What I like about this material ingenuity is that while not about sustainability directly, it achieves sustainable effects by a happy coincidence of her designs, which are constructed by hand rather than clipped out of larger rolls. Her innovations don’t require endless resources but rather make use of the what’s around in order to invoke a mood, a world, like the boundless imagination of a child. Her pieces to me act almost in the inverse of artist Ishi Glinsky, who goes to great lengths to faithfully imitate clothing processes, for instance mimicking metal studding on a leather jacket at a larger-than-human scale by retrofitting fence post caps.

Whatever her motivations, the stories she conjures through her garments have located their niche in short order. The designer, one year out of school, gets most of her business through commissions now, which begin in the $3,000 range. Kylie Jenner sent her Sedona/Arcosanti-inflected first collection viral when the celebrity soft bragged in a custom look of 6,000 healing amber beads while on a healing vacation in Utah. Maish’s popularity amongst influencers is another mixed blessing, one she had to face head-on when she got to LA. “Influencer culture dominates the scene here and they are used to this kind of world of giveaways,” Maish says. “It’s totally different for me and a brand like Gucci, who is able to send out clothes for free. But when I’m loaning something out it is often one of one.”

The kind of brand Maish wants to be is something she’s still working on. In the future she could herself follow a model like Rodarte, working with a small circle of employees, popping in and out of costume making, but at the moment she’s concentrated on what’s in her hands. To this end, the designer embarked on a personal challenge, finding ways of applying craft’s love of transparency to fashion. With most computer programmers, cooks, carpenters and knitters, it is customary to share methods with the community through plans and recipes, but in apparel it is unheard of today to share patterns, thanks in part to the knockoff economy created by fast fashion brands like Forever 21. Once a staple of American fashion, DIY patterns phased out almost completely when Vogue stopped promoting them, although a relic of this can be found at Michaels or Blick among the paper patterns that still bear the magazine’s name. Back in the day Willi Smith used to make his collections available as patterns and apparently so did Paco Rabanne, whose Disc-dress assembly kit (1966) inspired Maish to take a leap of faith and publish the steps for one of her designs as a digital download. “When people take on the aspect of making a garment themselves they have a chance to customize it and take your idea as a starting point,” Maish says. “In fashion that’s a foreign concept, especially now where we have accounts dedicated to designers calling out other designers. I thought the idea of exploring originality and copying would be interesting to tackle right now by testing out the avenue pattern sharing.”

Now she is at work on her upcoming collection which she will be launch primarily as a pattern book. “It’s a way of opening up the brand to a larger audience, Maish says. “The labor intensity in my pieces makes them prohibitively expensive to some, and I think in fashion we need to move towards a more inclusive model.” The joy embedded in Maish’s impossibly patient handiwork reminds me of John Ruskin's definition of craftsmanship: “the work of the fingers joined with good emotion and the work of the heart.” Maybe the craft community has the answers we need to fix fashion.