Berlin is unseasonably warm, but I don’t mind. It’s Gallery Weekend and I’m bouncing around the park-flecked city seeking out this year’s spring blockbuster at new galleries and old standbys like Sprueth Magers and Gallery Buchholz. The antidote to the art fair circuit, the annual event which highlights exhibitions throughout the city by invitation, provides artists the opportunity to take advantage of the unique architecture that characterizes the local scene. In my travels, I had the chance to speak up with four and dig in.

Rebecca Ackroyd | PERES Projects From the outside of PERES Projects, Rebecca Ackroyd’s life-sized figures are barely legible thanks to a transparent red film which coats the gallery’s signature storefront windows from top to bottom. This is the first hint at the British artist’s interest in environment and the way it reflects back upon the individual.

Through the doors, Ackroyd’s lounging bodies come into their own—basking in the pinkish light that bathes the white cube—they stare outwards into the world through helmets, goggles and sunglasses. Wax drips down their torsos, which are inset with ruby windows, hinting that perhaps their gazes aren’t fixed in collective wonder but terror a kind that emanates from inside out. “In the last few years I’ve really begun to think of national identity as a landscape, something that is in a sense inescapable,” Ackroyd says of the inspiration for “The Mulch.” “You can feel as though you are a part of something only to realize that it’s completely different than you imagined—and yet its still an a part of you.”

I follow her into a backroom which Ackroyd carpeted in a dark paisley. A “pub rug” she says. On the floor of swirling navy is a drain or a manhole with the artist’s initials carved in it. “Here, Her, Here,” read the spokes.

Her garage door-like sculptures, which are molded from blinds, speak more explicitly with UK and EU carved into their grey collaged facades. Ackroyd’s apocalyptic vision is as disturbing as it is enticing perhaps because of the pleasure you can see in the materiality of her drawings and fiery shells. Unlike peers with similar visions of the future, the artist doesn’t distance the human experience in order to create but rather complicates it with her own hesitations and conundrums. “My last show was called ‘The Root’,” Ackroyd says. “’The Mulch’ I see as a continuation. It’s the topsoil where a lot of the decomposition and confusion happens I thought it was a nice analogy for our time.”

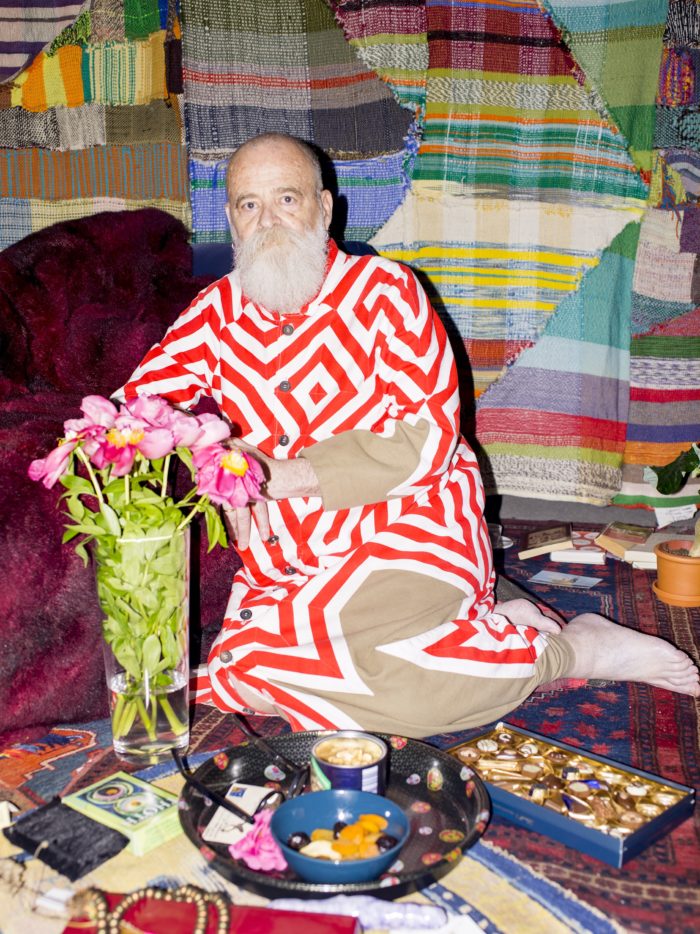

AA Bronson | Esther Schipper I meet up with AA Bronson on one of the final mornings of Garten der Lüste, his five-day exhibition at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin. He is on site as a part of Tent for Healing (in collaboration with Travis Meinholf), an ongoing interactive installation started in 2013 and recently acquired by the Stedelijk in Amsterdam. The hybrid performance-meet-sculpture seeks to provide personalize healing sessions to the public. “Twenty minutes is too short a time to provide real healing,” Bronson admits telling me the sessions are less about holistic healing but more focus on the letting go of objects of personal significance that are weigh one down. He lifts up a nameplate necklace donated to the tent by a recent visitor. “Her mother had given her this necklace and ever since her death, she had held onto it as a way to feel attached to her memory,” the Berlin-based artist says. “Recently she’s realized she feels her mother’s presence regardless and was able to let it go. It’s beautiful is it not?”

This item along with all the others collected over the course of the installations life are then inventoried by the Stedelijk. “It’s a preservation nightmare,” he smiles. “I think I’ve always like to stretch the idea of what could be considered an artwork or what function the museum could serve.”

The work on view at KW Institute is largely-based in the experiential. Bronson worked closely with a set of collaborators including a forest and musicians in order to keep the ephemeral landscape of taxidermied animals, petal mandalas and tents always active. However, at his Esther Schipper, the show is decidedly more static. The exhibition, “Catch Me If You Can!: AA Bronson + General Idea 1968-2018,” chronicles work from approximately fifty years–offering visitors the chance to see the journey that led AA BRonson from sculptures, paintings and zines to the Tent of Healing’s latest iteration.

Claudia Comte | König Gallery Claudia Comte’s work has always found its inspiration in nature’s patterns and structures but for her solo show at König Gallery, the artist expands this formal conversation in order to explore our impending, man-made extinction. “When Dinosaurs Ruled The Earth” takes the form of a monumental installation, one which required the artist to dangle a forest of trees from her native Switzerland through the former church’s skylights before blowtorching the bottoms. She tells me her neat rows respond to the gallery’s hidden architecture. Each trunk corresponds with a series of columns that are sealed beneath the floor holding us up. Perhaps the artist’s nod to our own dependencies.

Like past installations at Gladstone Gallery, Kunstmuseum in Luzern andArt Basel Meeseplatz, Comte’s environment is one of complete immersion with a soundtrack playing over head and the bittersweet smell of charred wood permeating the space. “I hope it stays,” she says of the aroma. “I like to activate different senses in chorus.”

The exhibition offers several firsts for the Berlin-based artist including an orchestra of 4-D cachpont animations that take the shape of her idiosyncratic bunny ears, serpents, hands and cactus sculptures (some of which populated City Hall Park in 2016 as a commission by Public Art Fund). ‘I wanted to see what these forms would do as water or something more fluid then marble or wood,” Comte says. “I see the videos as another evolution for me to play with.”

Another first is Comte’s move into bronze. There are several patinated cactus inset into the hanging trunks alongside other small pieces in her signature marble and polished woods. Amongst her normal menagerie, one finds a marble coke can and bronze water bottle–a response to Comte’s recent visits to nature’s remotest sanctuaries, Kyrgyzstan and Papua Indonesia, where she found evidence of Western plastic amongst the exotic wilderness.

When I ask her about her preferences for the organic, she points to the trunk’s visible rings as a kind of clock. “Materials of the earth have a different temporal quality,” she says. “Marble and wood can summarize an entire ecological era, a timespan that goes often surpasses our own.”

Christian Falsnaes | PSM Upon entering PSM’s second floor gallery space one I am confronted by a cacophony of human emotions from cheers to protests. “I wanted to play with the movement of the natural gallery weekend,” admits Christian Falsnaes, the artist behind the intense soundscape. “I like the crowds in the video don’t feel so far from the crowd of the audience.” The Berlin-based artist is referring to self the title of his solo exhibition and more importantly a new room-crossing, two-channel video installation investigating the different ways collective and individual occupy space.

Film and edited mere weeks before the opening, SELF, follows a troupe of hired actors (mostly dancers) as they march, crawl and scream through the spring kissed streets of Berlin. One video features a constantly rotating performer acting on their own, while the other, a group moving more or less in sync. The camera dollies in as they make their way down the sidewalk. Passersby, Falsnaes’ unpaid participants, rarely react let alone flinch as the screaming crowd yelling yes makes its way by.

Teasing out social dynamics is the foundation of Falsnaes practice. In SELF, the artist explores our tendency to rely on others for social cues. “Research shows that if there is an accident on the street, most people won’t react and it’s not because they aren’t compassion,” he explains. “It’s because in times of panic we are programmed to look at what the people around us are doing for social cues. We don’t react because others are not reacting. With this project, I was trying to cull out that sensation of moving as one.”

The performers in SELF face away from the camera as it dollies in. The anonymity creates a palpable distance and allows me to concentrate on behavior rather than features. “What I find interesting about the exhibition or museum space is that people view everything in it through an analytical lens so even if you yourself become involved in something that is very emotional or that touches you on a deep psychological level you still maintain this certain distance,” Falsnaes says. “I find that is very powerful to use these moments of strong feeling to reveal these underlying systems. On one hand its manipulative, but I try to use that manipulation to create a sense of deliberate transparency. All these power structures are so present in our day to day, but the people implementing them don’t want us to see them. I do.”

in your life?

in your life?