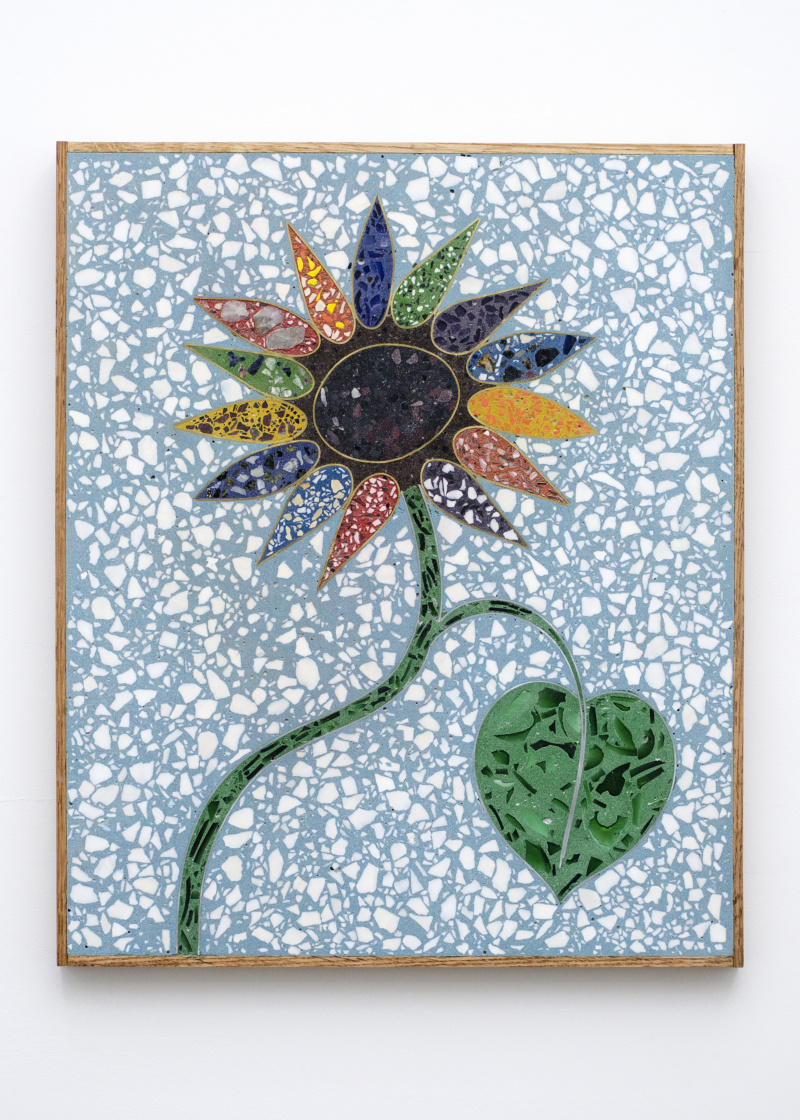

Around five years ago artists Ryan Bush and Raphael Martinez Cohen joined forces, each contributing a word to their new collective name. Cohen chose “Ficus” for its suggestion of tending to nature and “civilization putting down its roots,” fig trees being among the earliest domesticated plants. “Interfaith,” Bush’s idea, invites capacious spiritual thinking. One word localizes, the other transcends locale. The unifying of seemingly disparate ideas undergirds their collaborative practice, which, as Cohen explains, has “grown organically as we’ve stumbled through various crafts and modes of making.” Past modes have included everything from potpourri to an orange-peel-based water-filtration system and constructions made of fungus. Most recently it’s terrazzo that has caught the duo’s attention, which they use to make pictorial wall sculptures.

Terrazzo is trending, bedecking blandly contemporary hotel bars and high-end coffee shops in every city that has access to Pinterest. It keeps being, to borrow a favorite word of Ficus Interfaith’s, resurrected. (The duo titled their show at Brooklyn’s Deli Gallery that opened in October 2020 “Lazarus,” a reference both to the figure resurrected by Jesus and the 19th- century poet and activist Emma Lazarus.) Trends notwithstanding, terrazzo is a substance of circumstance: a composite of fragments of marble, glass, granite and other stones, often sourced from the cast-off or destroyed components of previous projects, suspended in a cement-like binder and smoothed over. It is itself a resurrection. Ficus Interfaith’s terrazzo images are not recapitulations of blush-and-blue Airbnb cosmopolitanism, but are rather born of a deep engagement with the history of their material of choice.

That history, which goes back at least to the 18th century (although some date it as far back as ancient Egypt), is connected with histories of mechanization and architectural engineering. Introduced to the United States in the late 19th century, terrazzo only became popular in the 1920s, when divider strips and electric grinding machines made it far more affordable and efficient to produce. It spread everywhere: federal buildings, private homes, Hollywood’s Walk of Fame. The mechanical process that facilitated terrazzo’s popularity in the 1920s is functionally the same that Ficus Interfaith uses, albeit at a small scale that leaves some suppliers frustrated. Strips of zinc or brass are soldered into forms, looking, as Bush puts it, “like a tray of cookie cutters.” In the goopy terrazzo slurry goes. “It’s sort of like paint by numbers,” Cohen says, with the big difference that until a piece is smoothed over it’s hard to visualize how it’s going to come out.

The source imagery for Ficus Interfaith’s recent exhibition similarly reflects the history of American manufacturing: 1930 Rockwell Kent prints of muscled male figures drawn as advertisements for railcars, and foam hats of the Statue of Liberty’s pointed crown that you find at tourist shops. Among the ironies in Ficus Interfaith’s work is their appropriation of symbols of mass industrialization for unrepeatable processes guided by a commitment to the notion of craft. Rather than material or mechanism, however, they center the maker. “The fact that we’re doing terrazzo ourselves is just as important as whatever imagery that we decide to make,” Bush explains, adding that the unidentifiable figures in their painterly appropriations of Kent’s drawings could be imagined as a sort of stand-in for the artists. “There’s a hierarchy we’re interested in disrupting,” he adds, taking aim at the boundaries between materials and practices attributed variously to craft or décor or architecture or fine art. “Crafty is almost an insult to a lot of artists—that excites me.”

in your life?

in your life?