With its potent depictions of racial violence and African American empowerment now more palatable to the mainstream, the explicit political content in Faith Ringgold’s early work is increasingly de rigueur. For some, its visceral message seems to match the complex feelings of rage, discomfort and empowered self-representation wafting throughout the zeitgeist, alongside discussions on gender equality, structural racism, white privilege, economic disenfranchisement and so on—conversations Ringgold was having with a group of black intellectuals and activists in the 1960s, continuing a lineage of thinkers from Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass to Harriet Tubman and Marcus Garvey, among others. Yet, Ringgold’s interests have taken her elsewhere in 2019. “I spoke about what I had to say at the time I had to say it,” are about the only words she wants to share regarding those early years.

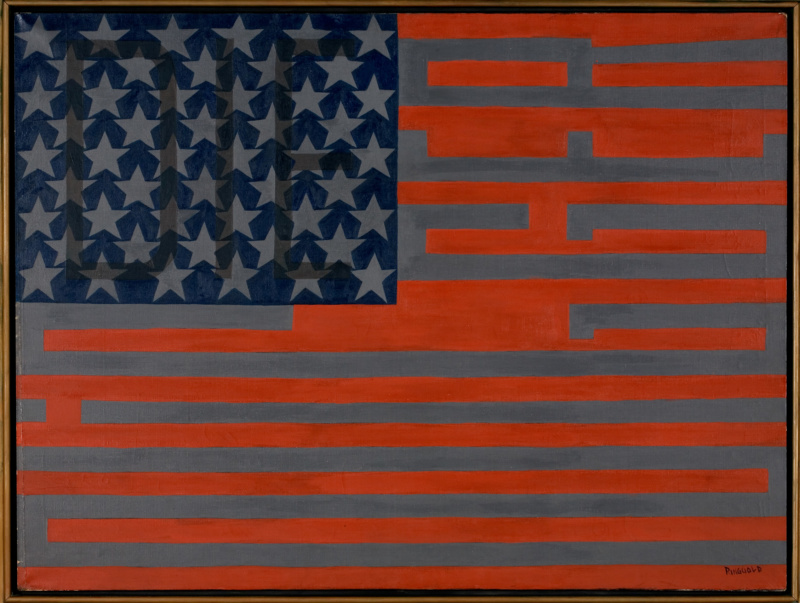

Those works are being considered anew within the art world. When I met her for this interview, her Black Light Series #10: Flag for the Moon: Die Nigger (1969) was in its last days as part of an installation where it was paired with Jasper Johns’s Flag on an Orange Field II (1958). On view at the recently opened Glenstone museum, in Potomac, Maryland, both paintings riff on the American flag—however in vastly different tones. Ringgold addresses the vicious political climate of the 1960s by inserting the phrase “Die Nigger” within the stripes of her flag. In regard to Johns’s more spare representation, she says, “To me, that wasn’t enough. I mean, what do you say about the flag? Why is it just a flag? But that’s the way artists were in those days. They didn’t want to say anything. I guess they figured they would say the wrong thing. Somebody wouldn’t agree or this or that. I didn’t have that impression. I wanted to say what I thought, how I felt.”

In the 1960s Ringgold’s politically charged “super-realist” oil paintings were ignored. Now, she is preparing for a solo show organized by Hans-Ulrich Obrist at London’s Serpentine Galleries opening on June 6; the release of a BBC documentary on Ringgold’s life and work will coincide with the exhibition; and her work is on tour in the blockbuster exhibition, “Soul of A Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963–1983,” currently on view at the Broad Museum in Los Angeles. “I was immediately struck not just by her radical painting and publishing career, which spans over 50 years, but also by her active involvement within the Civil Rights and Feminist Movements in New York,” says Obrist of his first meeting with Ringgold. “Now in her eighties, Faith is widely considered to be one of the most significant artists of her generation, a great inspiration to younger artists, including Grace Wales Bonner and Lynette Yiadom Boakye, both of whom have exhibited at the Serpentine Galleries.”

Part of Ringgold’s consistent output can be attributed to her nearly 25-year relationship with Dorian Bergen of ACA Galleries. “I looked around and realized I needed to dedicate one staff member to take care of Faith,” says Bergen. “That was back in 1995. We realized we are cut from the same cloth. The same work ethic. She’s up by 6 or 7, arms ready to work. I’m the same. We’re worker bees.” One of Bergen’s first ideas was the organization of a traveling exhibition that showcased the breadth and depth of Ringgold’s oeuvre. The show has been on the road since 1996, breaking attendance records, and presented at nearly 50 institutions so far.

Ringgold’s jubilant spirit, robust laugh, and healthy sense of entitlement seem to illuminate her choice to live in a present moment defined by her own interests—a joie de vivre nurtured during her Harlem childhood, an extraordinary period of African American creative and intellectual output. Although she was not taught about African or African American art in school, she was surrounded by it, with figures like Langston Hughes, Aaron Douglas and Billie Holiday in the ether. “All those guys were living around us in Harlem. Isn’t that something? You walk down the street and you run into them. I knew them, but I didn’t know about them. I didn’t know they were as great as they were. And I don’t think they knew either, because they didn’t allow a whole lot of excitement,” she says.

Ringgold has worked in 16 different mediums—ranging from prints, drawings, and story quilts (painted canvas framed with fabric) to works on paper, soft sculpture, illustration and more—continually and thoroughly engaging race and racism, womanhood and feminism, and a lifelong love of storytelling, exemplified by more than a dozen children’s books she has published. Her iconic work on race riots in the US, American People Series #20: Die (1967), influenced by Picasso’s Guernica, was acquired by MoMA in 2016. Discussions are underway with the Brooklyn Museum on an extended loan of For the Women’s House (1971), an 8-by-8-foot oil painting installed in the women’s prison at Rikers Island in the early ’70s. The work foreshadowed advances for women in the workplace and was vandalized when the prison was converted to an all-male facility. Begun in the 1980s—after making her Tibetan tanka-inspired works in the 1970s—Ringgold’s infamous story quilts offered an outlet to tell her own autobiography through a combination of painting and text that she still employs as an artistic strategy.

Ringgold’s series California Dah, among her abstract output, is installed prominently in her living room. Made in the ’80s while she was living beachside and teaching at the University of California at San Diego, California Dah is a large-scale five-part series of paintings with raffia fringe acting as a frame. The work was a response to her mother’s passing. “I wanted to see what it looks like where she was. What is that like? Where is she and what is she seeing? I came up with these shapes. The colors and the shapes. What colors do you see? What shapes do you see?” The works suggest Ringgold could have had a parallel life as an abstract painter.

Now, as the second decade of the 21st century comes to a close, what is most on Ringgold’s mind is aging. In fact, it anchors the working title of her next body of work, “Aging-aling-aling.” “I want to get into aging because it’s the one stage in your life that doesn’t stop. Once you reach aging, that’s it. You go on aging, aging. Aging-aling-aling.” She continues, “People are aging into living longer and longer. And I’m fascinated with the possibilities of what that can be and what it could look like. That’s what I’m concentrating on right now, because I’ve noticed that images of old people have a certain look.”

Ringgold’s loft-style studio, on the second floor of her ranch house in a wooded area of New Jersey, looks like the comfortable abode of an artist well-acquainted with her own craft, quirks and necessities. A vast array of seating, art materials, pieces from her archive and works in progress fill the space. A sense of ease fills the air, the perfect ambience to allow her ideas to unfurl. “I have to get it in my head and feel it, see it—so that I can paint it,” she says.

An unlikely character in her investigations into aging is none other than Donald Trump. She laughs, chuckles, and shakes her head when she says, “He’s amazing. He’s absolutely amazing.” She means as a humorous muse. A yellow plastic file folder holds pages of downloaded images of the commander-in-chief. Written on the cover: “Trump the Chump.”

In Bergen’s estimation, Ringgold does not like or dislike him. “She doesn’t want to demonize him. She wants to understand him, so she’s working it out.” Sketches on 8-by-10-inch white paper depict Trump’s head in a variety of profiles and frontal views in either one of two styles: colored drawings that feature vibrant yellow hair and a respectfully humanized rendition of his face, or black line drawings that seem to reflect the deeper cerebral negotiations going on in Ringgold’s mind. The black-and-whites are striking and call to mind the work of Francis Bacon. They are both simple and complex, showing faces that all feature just one large eye situated above the bridge of Trump’s nose.

“I think I’d like to include him in my ‘Aging-aling’. Because he’s definitely aging-aling. I don’t know why he’s so crazy. See this here? This is hair that has been taken off different parts of his body. Maybe it’s taken off the back, wherever it’s plentiful. It has a permanent bend to it. In other words, he can’t get that to lay down so he just made it into a hairdo.” Bergen is in the midst of planning “The Wise Get Wild” party as a bit of inspiration for Ringgold. The fête, taking place this spring, will bring together elders who are active poets and chess players and have romantic partners and lots of friends. Look for Ringgold’s take on the golden years in an exhibition in 2020. In the meantime, visit her app, Quiltuduko, her digital response to aging—a visual art-making adaptation of Sudoku.

in your life?

in your life?