It seems fair to say that no piece of furniture is so venerated by the design cognoscenti—or as widely recognized as peak mid-century—as Charles and Ray Eames’s molded plywood lounge chair. In the permanent collection of over twenty museums in the United States and Europe, the modernist leather recliner, inspired by a well-used first baseman’s mitt, along with its matching ottoman, earned cult status almost immediately upon hitting the market in 1956. As iconic post-war symbols go, the couple’s ubiquitous stacking seats come in a close second. Conceived for MoMA’s 1948 International Low-Cost Furniture Competition, the fiberglass shell chairs evoke a perennial Mad Men brio, despite a deliberate price point aimed at mainstream America. At present, they do indeed proliferate, from a barber shop in Santurce in San Juan, Puerto Rico to a McDonald’s near the Freedom Tower in lower Manhattan. Famous for declaring, “the details are not the details; they make the product,” Charles Eames eliminated the extraneous. It’s an edict we now take for granted. Decades hence, democratic design practices built on function, quality and experience have thrived, from IKEA (“At home isn’t just a place. It’s a feeling.”) to the iPod (“form follows emotion”).

No less integral to their visual style and world view, yet less examined, are the many films that Charles and Ray Eames also created from the 1950s to the ’70s. A hyperconscious elevation of the seemingly mundane permeates each frame and crystallizes their pared-down aesthetic. And for today’s viewer, the films feel all the more prescient alongside the unflinching gaze of social media.

“I like to joke that if the Eameses had Instagram, they would be really good at it,” says Amy Auscherman, who oversees Herman Miller’s corporate archives and, in 2018, began collaborating with the Library of Congress to preserve the film collection for public record (Herman Miller’s marketing budget saw the endeavor through). “The Eameses were obsessed with the details, whether how big the world is, or how small parts of it are, down to the way a foot of a chair is positioned,” she explains of Charles and Ray’s oeuvre.

With some hundred and twenty credits, as well as clients like Boeing and Polaroid, the pair trained their eye on both the stunningly banal—think soap bubbles and toy tops—and the vast complexities of time in the dawn of the computer age. Perhaps their best known short, Powers of Ten (1977), was distributed by IBM. The dizzying nine-minute sequence begins as a scenic shot of a man lazing on a striped picnic blanket before zooming out exponentially by a power of ten, every ten seconds. In an instant, we are floating above earth, then in the far edges of the galaxy, before plunging back down to the park scene and eventually landing as an atomic speck within a blood cell on the picnicker’s hand. In Blacktop: A Story of the Washing of a School Play Yard (1952), Charles, intrigued by a janitor washing a schoolyard across from the Eames office, created a series of trippy close-up visuals that capture soap bubbles and the flow of water across asphalt with a handheld 16 mm Cine-Special, set to Bach’s Goldberg Variations.

Critics generally sort the Eameses’ filmic output into two categories: the toy films (the Eameses were also master toy designers) and the idea films, Powers of Ten a signature of the latter. But the couple also shot a charming body of work that exhibits their design process—a treasure for mod furniture junkies. There’s Soft Pad (1970), which looks, to the 2020 mind, like magnificent plein air Instagram footage of their office chair, and Eames Lounge Chair (1956), a stop-action film that constructs the iconic recliner piece by piece. Sofa Compact (1954), technically a sales video for Herman Miller employees and consumers, which features office staff and friends assembling the flat-packed Eames Sofa Compact, is poetically sparse and alluring in its own right.

“Charles and Ray were always taking detailed shots of vignettes around their house or the way light was hitting a wall,” Auscherman explains. She points to what’s likely their most intimate film, House: After Five Years of Living (1955) which displays, in just eleven minutes, hundreds of meticulously curated images of their famous Case Study House #8—from an Eames chair’s window reflection to a meal tableau on a blue-and-white patterned tablecloth (portending the popularity of food posts over a half- century later).

The Eameses’ aesthetic is also the visual primogenitor for brands such as Net-a-Porter who blend commerce and lifestyle with editorial layouts akin to a fashion or design publication (as well as the print magazine Porter), offering as much a mode de vie as products for sale. In the grand Eamesian film tradition, KULE—a luxury children’s collection founded in 2001 and relaunched in 2015 as a brand built on the perfect striped shirt—created its first lifestyle video collaboration this year, to delightful effect. “We often play with a nostalgic vibe in our products, which is funny when juxtaposed with modern technology,” says the company’s president, Jim Kuerschner, of their project with stationary engraver Dempsey & Carroll. “The concept of the film centers around the question: what would you do if you lost your phone?” Only 60 seconds long and shot by F. E. Castleberry on the Upper East Side, the clip explores a young woman writing a letter and is as much a one-minute immersion as it is an advertisement. “You can really live your life in KULE, so it was important to show the joy in everyday moments, whether sitting at a cafe, shopping at your local bodega or mailing a letter,” he explains. “Why not throw on your white fur coat to go buy a stamp?”

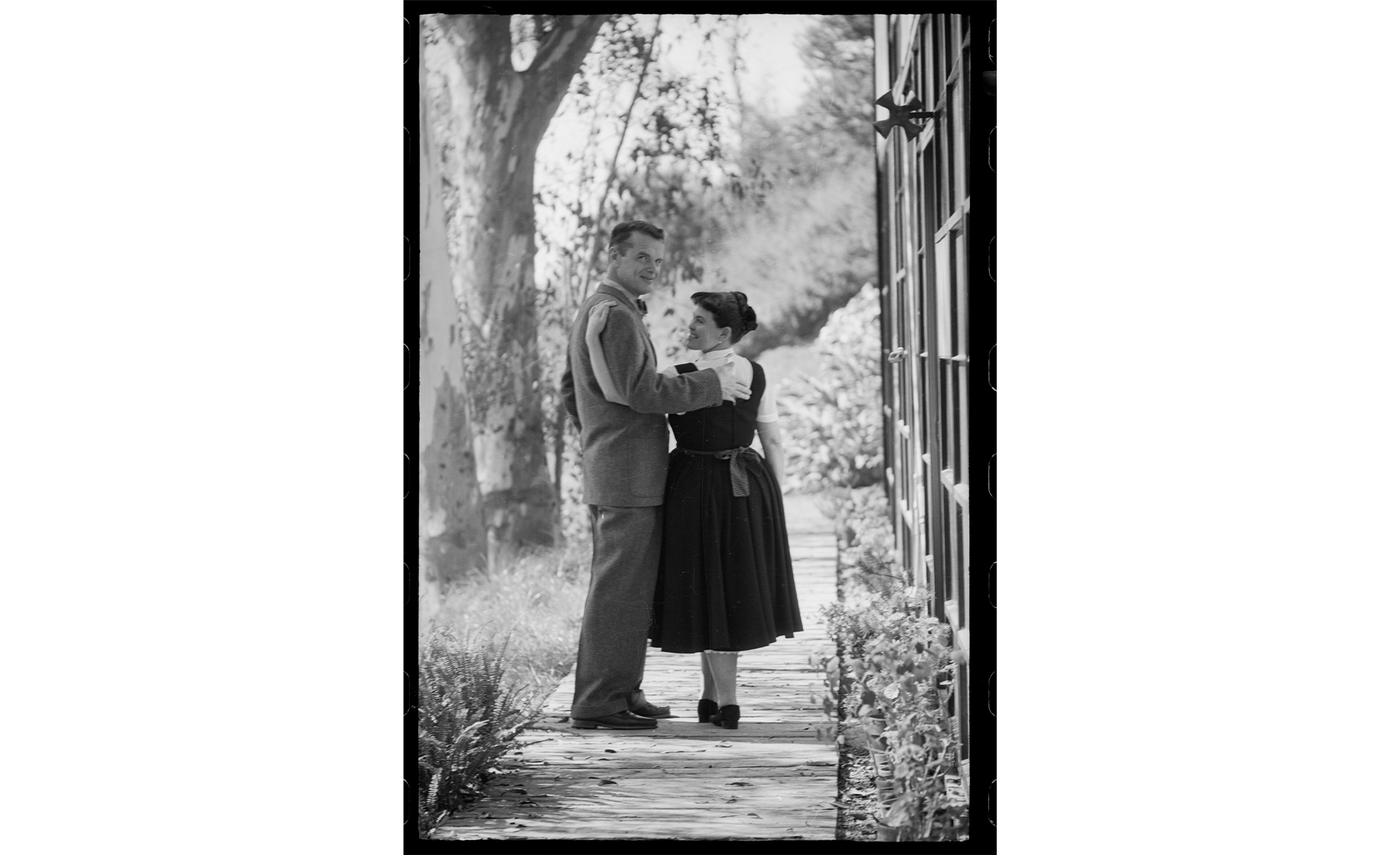

“In their time, the Eameses were not only designing products, but were also put forth in the media as people whose lifestyle was interesting—a way of life that was new and possible after World War II,” reflects Auscherman. Seventy years later, the sublime power of iPhone photography in our hands, we may have finally caught up with them.

If you, like the Eameses, are curious to learn more about the technical specifics of Herman Miller and the Library of Congress’s restoration of this film archive, head to WHY to find an intimate narrative about the multi-year project.

in your life?

in your life?