Harmony Hammond

Site Santa Fe | 1606 Paseo de Peralta, Santa Fe, NM

Through May 19

A slanted rectangle of desert sunlight slid into the whitewashed room through a side window, illuminating a mason jar full of white tulips on a low, makeshift table. In the corner fireplace, piñon was burning, releasing its warm, slightly sweet fragrance. The early morning was quiet and still, save the soft crackling of the fire and the softer sound of my partner on the couch beside me, writing intently in a notebook. The air felt slightly chilled, making the radiating waves of heat all the more pleasurable. Taking a sip of coffee, I had a thought that I’m grateful for whenever it arises: This is a perfect moment of life on Earth.

I opened the book I’d been reading, a collection of early Buddhist texts. After his awakening, Buddha points out to his disciples the dire mistake of people who are “infatuated,” who are “utterly committed,” to the sensuous beauty of the phenomenal world; how their—that is, our—senses are cords that bind. They tie us like a fawn caught in snares, he says, rendering us helpless in the forest. “He has met with calamity, met with disaster, the hunter can do with him as he likes, and when the hunter comes he cannot go where he wants.” I looked up from the book to again survey the beautiful moment and found every element just as perfect as before. FUCK!, I thought, I’m not getting out of this!

We had driven out to this idyllic house in Santa Fe (loaned to us by our friend, the great writer and psychonaut Bett Williams) to escape Brooklyn for the desert—and to see Harmony Hammond’s major survey, “FRINGE,” at Site Santa Fe. Later that morning, I finally went alone to see the exhibition, which brings together 24 of the artist’s large-scale “near monochromes” spanning 2014 to 2024. It is the latest instance of welcome, well-deserved attention to a remarkable career. In recent years, Hammond’s work has been shown more than in previous decades, chiefly in a series of elegant exhibitions at Alexander Gray gallery in New York, as well as in last year’s Whitney Biennial (not to mention the inclusion of her pathbreaking feminist works from the 1970s in “Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction,” curated by Lynne Cooke, which opens at MoMA in New York this month, following stints at LACMA in LA and the National Gallery of Art in DC.)

At 81, Hammond is nothing short of a living legend. Since the ’70s, she has helped define the intersection of feminist and queer art discourse, as a co-founder of A.I.R in 1972 (the first nonprofit, cooperative gallery for women artists in the country), and a founding member of the Heresies Collective. (Her essay “Feminist Abstract Art, a Political Viewpoint” was published in the first issue of Heresies magazine, in 1977, prefiguring her still unsurpassed monograph Lesbian Art in America: a Contemporary History, 2000.) Hammond’s important work as a critic, curator, and teacher would be enough for her to stake her claim on American art history, but there is still more than a half-century of genre-defying, mixed-media paintings, sculptures, and installations to account for—a body of work that has challenged masculinist, Eurocentric hierarchies of craft and labor with its influential use of domestic materials. Early in her career, Hammond used woven and braided textiles as a formal means to address women’s and, particularly, queer women’s experience. And, while she has advocated strongly for the political importance of representational and figurative work, her most significant contribution has been her pursuit of this content through abstract form.

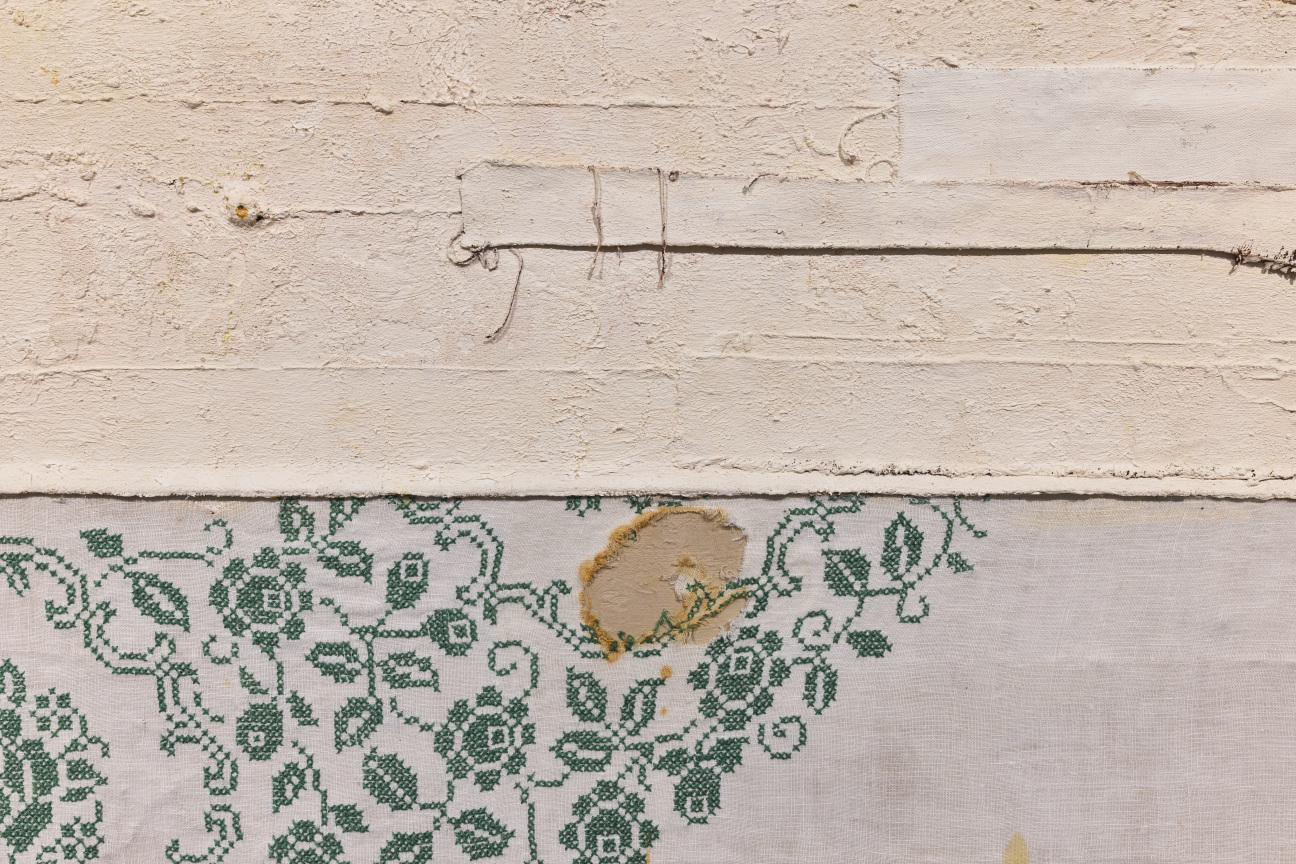

The paintings here, in “FRINGE,” appear more or less the same: large rectangular canvases that have been covered with swaths of burlap (sometimes in central cross shapes) or clad with strips as though bandaged. These textiles are submerged and affixed upon the surface in layer upon layer of dense, full-bodied oil paint in a range of off-whites, sometimes dipping into rust or tan, punctuated by simmering near-blacks and bright, pulsing scarlets. And generally, the works’ visual structures marry modernist grids with tufted quilts. But, seeing a large selection of these recent, strikingly minimal paintings (this exhibition constitutes roughly a third of her output of the last decade) allows the subtle differences between them—and their deeper meaning as a group—to emerge.

Paintings in general demand our looking closely, but this kind of abstraction does so more adamantly, insisting that we observe exactly what’s there. One way to start is by attending to how each part touches the others—and the surface to which it is affixed. Sometimes the elements overlap, or just abut, or leave a zone between them—the strips will go right up to the outer edge of the stretcher bar, extending beyond it in a kind of frozen frill, or they will withdraw from it like a wave retreating from the shore. Noticing such specificity sensitizes the edges of everything—between the parts of the painting and the whole, and between the painting and the world, the wall it’s on, the room it's in, and the bodies of those looking at it. And in precisely this way, Hammond and her paintings know there is no clean place to cleave our knowledge of the work from our larger knowledge of the world; it is only a move of violent ideology that separates things into distinct categories like "life" and "art." Which is to say, Hammond’s paintings ask us to bring our whole selves—every aspect of our senses, associations, and memories are relevant to our experience of them.

All of this unfolds differently from one painting to the next. Take, for instance, three compositions that deal with doubling. In Double Cross I, 2021, a diptych is created on a large horizontal canvas by two cruciform shapes that mirror each other across a central axis, in two colors, reddish and blackish, respectively. Double Bandaged Quilt #2 (Horizontal), 2019, appears to have a similar compositional logic: two squares, side by side, one mustard, the other russet. Upon closer inspection, they are two separate canvases pushed very close together, but because of the thickness and irregularity of the painted fabric, a slice of negative space quivers between them, charging the relation of just touching. In Fringe, 2020, a similar buildup of concentric bandages on two vertically stacked rectangles, this time both in cream, appear to be on a single set of stretchers; viewing them from the side reveals that they are, in fact, two canvases joined with a brace, the wooden bar and screws all heavily coated with paint. These three pieces open a whole discourse of coupling—of how two are one, and one is two, and every possible permutation is suspended between them. In this way, formal operations become metaphors for the erotic.

Given how influential Hammond’s writing, lecturing and theorizing have been for so many artists and scholars, I believe it is important to try to take the paintings on their own terms, without collapsing them back immediately onto their maker. However, spending time with the artist, with her immaculate short platinum ponytail and studded black leather jacket, and experiencing the austere elegance of her home in rural Galisteo, New Mexico (a 1930s wool barn she renovated beginning in 1989, making a Southwestern version of a New York loft), I find there is an undeniable congruence between her life and art, so much so that her strong, generous personal ethic permeates the formal dimensions of her paintings. Like her, they are incredibly sexy and smart, physically charismatic and yet deeply introspective.

Their specific sexuality is thematized by Hammond’s use of grommets, which tease openings into the interior of the painting, or become thick knots of paint so they protrude as lips or nipples, or simply a highly charged locus of touch. The variety of textures, from heavy burlap to fine, domestic linen, is amplified by the sensate brushwork, which is stippled or applied in various directions, playing with and against, at times emphasizing or obscuring the overlapping surfaces beneath. It endlessly returns the viewer to a feeling of the surface as skin, furthering the overall sense of the canvas as a surrogate for the body. The straps and fetters, ties and ropes that construct these paintings are at times assuring and embracing—the very stuff that holds the painting together in maternal gestures of repair. At other times, the same forms feel dominating in a sexy way, like a corset or some kind of formalist shibari, or repressive, evoking the specter of gendered violence. When the red paint coagulates like blood (not only menstrual blood), when a pale trace of subtle color mellows into a bruise or wound, it signals an undeniable violence that permeates the work. It might be the continual threat of violence that women and queer people are subjected to every day in this particular political reality, but indeed it may also speak to the inescapable reality of pain and fragility that comes with inhabiting a mortal body.

Looking at one of the earlier works in the show, Things Various, 2015, a porcelain-slip colored painting embedded with crisscrossing canvas straps, you see a point where a strap is cut, is lifted off the surface, and through its grommets, two halves of a cut rope dangling down, brushing against the face of the painting, echoing the all-over brushwork below. Once you are attuned to the language of these paintings, this evidence of a cut knot is almost gutting—something once joined is now forever held at a particular moment of disconnection, within a larger composition that is otherwise secure, resolved. It made me realize that the true content of these paintings is attachment in all its forms; they are about our clinging bonds with each other, with being together in this shared world.

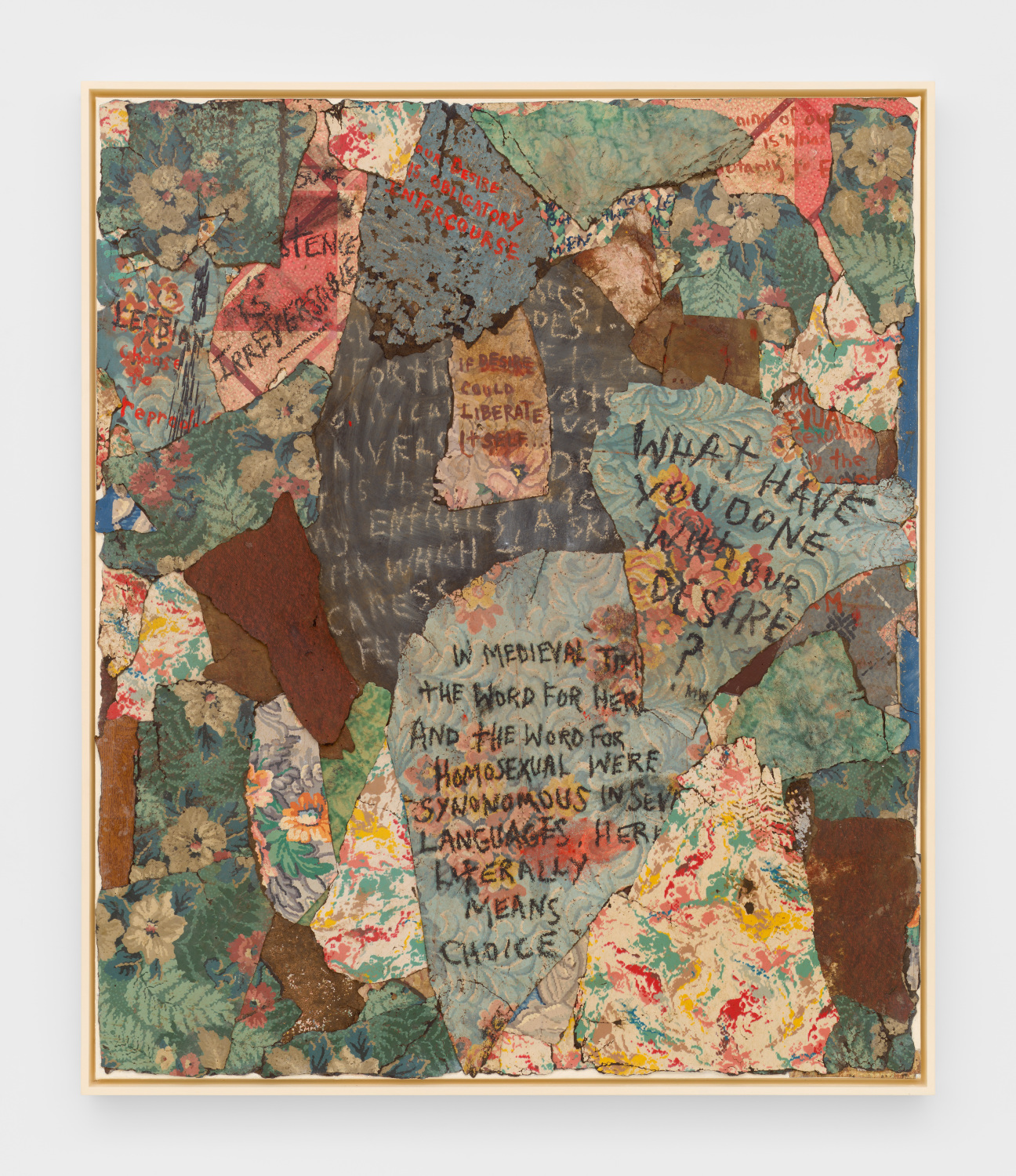

This is probably indicated most directly in Voices I, 2023, for which Hammond collaged decaying bits of floral linoleum (scavenged, as are most of her materials, from abandoned homesteads across the Southwest), and then painted a quotation from the radical lesbian philosopher Monique Wittig. At the very center of the composition is the fragment, “if desire could liberate itself…” Yes, if. And like the image of the fawn bound in the glade, the cumulative effect of these paintings is poignant, profound. That’s us—people who are enamored with the sensuous beauty of being in the world, which is what painting is all about. What comes across more than anything here is the incredible belief Hammond has in art, and in form’s ability to communicate the deeply felt dynamics of her own human experience. The work is about what it’s like to try to love the world enough to change it; to give everything you have to your friends and lovers; to attempt to communicate this with anyone else who might care enough to look; to want to be free, all the while knowing that there is no escape.

Jarrett Earnest is a writer and curator living in New York. He’s recently authored monographs on Sam McKinniss and Dana Schutz, both out this spring.