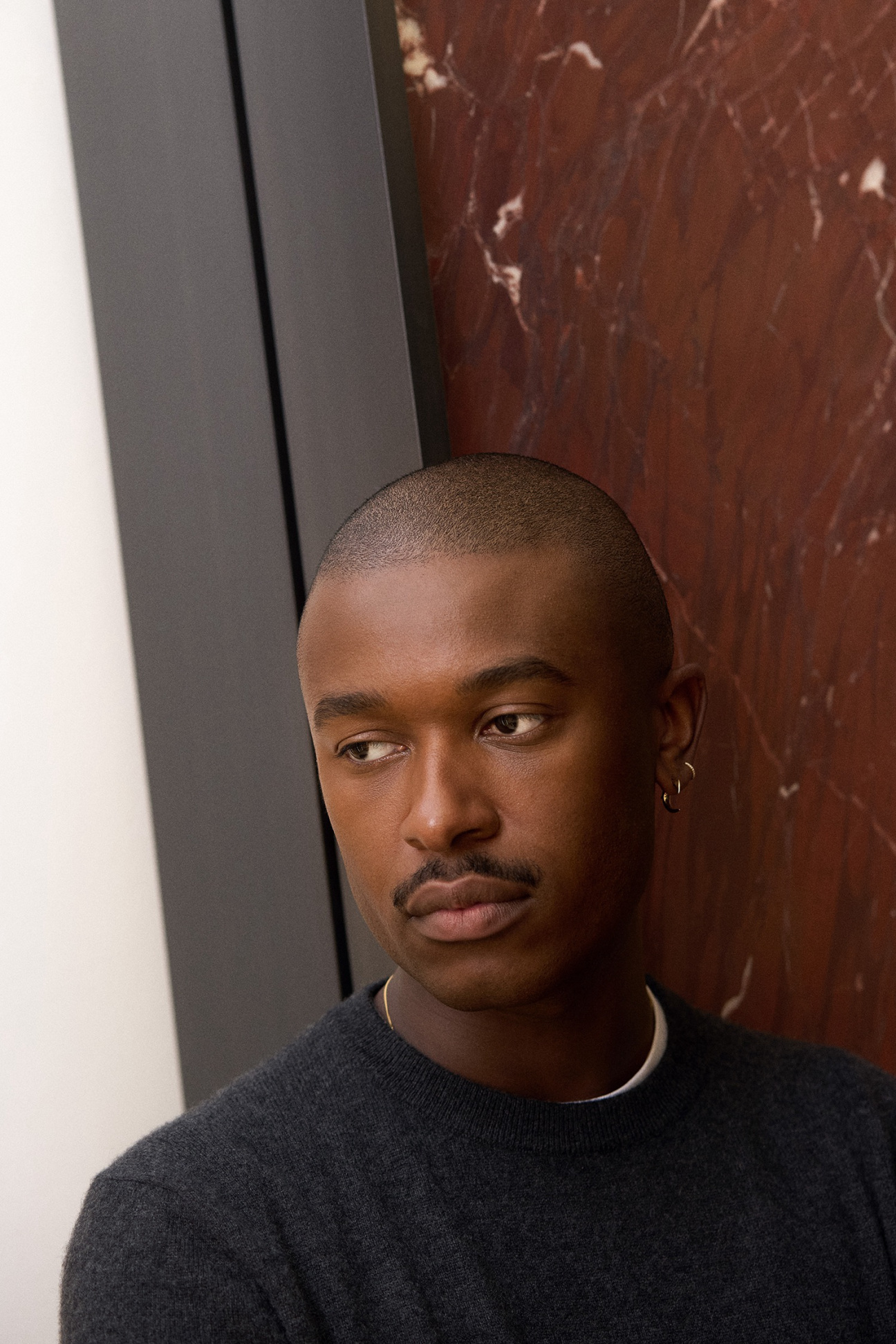

At first glance, the 42-year-old visual artist Alvaro Barrington and Maximilian Davis, the 30-year-old creative director of Ferragamo, have little in common aesthetically. Barrington, who is the subject of solo exhibitions at Thaddaeus Ropac in Seoul (through April 12) and Sadie Coles in London (March 5–April 26), is known for creating immersive installations that are kaleidoscopic in color, texture, and sound. Meanwhile, Davis—one of the youngest creative directors of a major fashion house and a favorite of the first-name crowd (think Beyoncé, Rihanna, and Kim)—is known for clean lines, pared-down silhouettes, and the slick use of leather and lamé.

Yet, the duo has a long list of shared influences, from dance to their grandmothers to Carnival and other cornerstones of Caribbean culture. (Barrington grew up between Grenada and Brooklyn; Davis was born in the U.K. to Trinidadian-Jamaican parents.) Both men are also committed to infusing the often-uptight worlds of art and fashion with a sense of dynamism, community, and play. In the following conversation, they compare notes on the creative process.

Maximilian Davis: I went to Frieze London [last fall] and saw this piece of yours [featuring American rapper DMX] that made me giggle so much. When I first saw it, I was drawn to the colors and the craft that went into it. I had no idea it was DMX until the gallerist held up his phone with a picture of him. To me, it was a personal moment because I remember [listening to] Ruff Ryders growing up. My sister had a T-shirt with [them] on it. I’ve always found it interesting to bring more personal research into my practice.

Alvaro Barrington: One of the things that makes our practices exciting is that it feels like the world is catching up to the culture we grew up in as a form of value. DMX brought this energy after the vacuum Tupac left behind. So much of rap is about craft—it’s about your ability to put words together in a certain way. [In your practice], you sometimes get associated with minimalism. You’ve reduced the language to start thinking about not only the craft of tailoring, but also culture and all of those things you can build out from it.

Davis: When I started my brand [Maximilian, in 2020], I had the desire to do a lot more research into my grandmother’s heritage. I remember going to Trinidad for Carnival every year, but I had no idea why I was going or why it existed. It’s not something I was taught in school, and it’s not something my school could ever teach me. When my grandmother passed away, I was going through all of her stuff, and that led me down this path of understanding her and the heritage of my family—like the reason why my great-grandmother moved to Trinidad, and why my grandmother moved from Trinidad to the U.K. There was so much richness in that heritage, but my aesthetic was the complete opposite. Like you said, it’s very restrained in a way. But when two things don’t speak to each other, I find that tension to be the most interesting starting point. It becomes something unexpected, something that people can talk about or question. And if you’re creating work that leaves people questioning, you invite them into your universe, which is what you do as well.

Barrington: That [reminds me of] the distinction between how Richard Serra uses minimalism versus how Felix Gonzalez-Torres uses minimalism. With Serra, it was really about a reduction that was about industrialization, whereas with Felix, it was more about a reduction to think about the body. One of the most meaningful artworks that has ever existed is [Felix’s] “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers). It’s just these two clocks—[a metaphor] for him and his partner Ross [Laycock], who both had HIV. As one clock’s battery started to die before the other clock’s, just like their bodies started breaking down at different points, the timing became off. That was an extremely poetic, minimalist reduction. I was looking at some of your runway shows, and I felt that same kind of tension, where it’s about opening you up to other things.

Davis: When I make clothes, I don’t want the clothes to wear the people. They need to wear the clothes. There’s so many different reasons for wanting to wear clothes. The one thing I understand so much more now—especially with the way that people are dressing and buying and making things—is that the sense of comfort, whether it’s mental or physical, is super important. If you are comfortable, it shows in how you’re carrying yourself.

Barrington: It’s about authenticity, I guess. Authenticity was so much a part of the culture I grew up in. You could tell by the words that would get made up, like “keep it real” or “keep it a hundred.” They’re all saying the same thing: Be yourself, don’t be a fucking bozo. Versus, maybe the generations in the ’70s and ’80s, when I look at some of their outfits, it was more about a “bigness.”

Davis: In the ’70s and ’80s, people were just living the way they wanted. They were very carefree, and that expression of freedom was obviously translated into clothing. I was having a conversation with one of my designers, who had found a book of fabrics. I was like, “This is insane. The colors are so great. When is this from?” And he was like, “The 1920s.” If we were googling what people were wearing in the 1920s and ’30s, we’d only see everything in black and white. But because of this one book, I have a slightly better understanding of the colors and prints being worn at that time. It’s great that we’re able to see the references from the ’70s and ’80s—the freedom and all of the joy that was put into the parties, the music, the lifestyle, the clothing.

Barrington: What I love about fashion or art is that if you do research, you’re like, “Oh, this thing had so much life in it.” It’s not just this Wikipedia page of history that we’re reading. [Picasso’s] Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is like Tupac’s “I Get Around.” Picasso’s moving to Paris; he’s a foreigner and having sex with a bunch of sex workers. One of them might have given him an STD. You realize that people 150 years ago were living just as crazy lives as we are today. There are people that make incredibly wonderful, innovative decisions in every generation. We forget that we have so many answers in the past, and that you can remix them. That’s what I loved about growing up in my generation of hip hop. It was about the remixing of something, then chopping it up, screwing it up, slowing it down. Do you have a soundtrack at the moment?

Davis: Every season I make a playlist of what I feel suits the mood of the collection. The only person I share it with is Yasmina Dexter, who does music for our runway shows. We have this back and forth on music and what we feel the show is about. It ranges from 12 to 30 songs. It’s everything that goes through my mind in a collection, but in music.

Barrington: I was talking to a friend who said, “When I see something great, I feel it in my coochie.” I wonder if there’s a similar analogy for you. Do you design clothes through a feeling in your body or your mind? Like I feel it in my ego.

Davis: Definitely. When I hear a certain song, it sets a mood, which then reflects a color or a sense of movement, whether it’s how the model’s walking or the fabric that the model’s wearing … I’m a daydreamer when I’m by myself. I find that when I go home, I’m not watching TV or reading a book. I sometimes just sit there and create a world in my head. When I do a collection, I daydream about what the collection will look like before I even know what the mood and the concept is sometimes.

Barrington: That’s sort of the definition of an artist: You live in a thing that hasn’t been created and then you fight your way to get it created against a system telling you that you’re certifiably crazy.

Davis: That’s where the tension comes from. Only you want it there and only you can understand it. And now it’s your job to make it clear for other people. Obviously, I’m not saying all my collections just come from my mind. When I first started working at Ferragamo, I would go into the archive every season. With my Spring/Summer 2025 collection, I knew that I wanted to talk about ballet. Salvatore was known for making shoes for people in different professions, including dancers. I found that Salvatore made shoes for Katherine Dunham, who was one of the first Black ballerinas. It opened up this whole new world for me.

Barrington: I have a similar creative process. I’m obsessed with the body and performance. Before I even started agreeing to gallery shows, I organized a series of concerts and performances. I really wanted to see the Alvin Ailey show at the Whitney because there’s a lot of overlap in terms of dancing and painting and innovation. This year, we’re going to do a bunch of performances, including these ballet plays with my paintings as a backdrop.

But what’s so special about the jobs that we have is the curiosity that unfolds into this engagement with history. It’s probably the greatest gift. You’re talking to history, you’re talking to the present, you’re talking to life. Maybe the best part about working at a heritage house is the research?

Davis: The research is the peaceful part.

Barrington: I really like that you talked about your grandma earlier, and going back to Trinidad and seeing that innovation that she was doing, then bringing that forward.

Davis: You have to be authentic for it to feel rich. Another reason why I decided to research my grandmother and my heritage was that I was working for brands beforehand, and I was really just doing research for them. It just wasn’t personal for me. I felt like the only way I could cut through the noise of what was happening in the world at that time—in lockdown—was to talk about what I could actually talk about with the most confidence. There’s so much that came from educating myself, my friends, and my family about what Carnival is. It’s a celebration of freedom.

Barrington: One of the things you bring up is being comfortable in your body. Compared to American culture, the Caribbean is so much about embracing your body. In Carnival, you’ll see a 300-pound guy in a bikini, and he’s having the best time of his life. I wonder how much of that comes from being allowed to embrace your body versus having to protect your body.

Davis: I grew up in Manchester—nothing like Trinidad or Jamaica, where my parents were from. When I was growing up, my sisters would want to wear miniskirts or bikini tops, and my parents would say no, which created the desire to question why you can’t wear these things, but also [to] rebel against what they’re teaching. Again, it creates a tension where you need to explore more to make it make sense.

Barrington: One of my professors always said that there’s no great work without tension.

Davis: For me, and maybe for you as well, I feel like this is the beginning of history. I don’t want to sound arrogant, but what we’re able to do, and the platforms that we have to express our work, is amazing. I remember growing up and not finding many reference points for myself. And I just hope that we can be a reference for so many younger generations and keep going.

Barrington: What’s really cool about this is that we are young. I’m relatively young for painting, even though I feel old. But fashion and painting are two industries in which you can age. You have so many great legacies of all the fashion designers making work well into their 70s and 80s, like Vivienne Westwood or Karl Lagerfeld. It’s the same thing with painting. I feel like my job is to age gracefully and still be interesting when I’m 80, at least to the people of my generation and hopefully to those a little younger and older. I want to have my meltdown stage and be okay. I want to take risks, say shit I shouldn’t say, do things I shouldn’t do, make work I shouldn’t make, but at the end, just age gracefully.

Davis: Let’s check in again in 20 to 30 years.

in your life?

in your life?