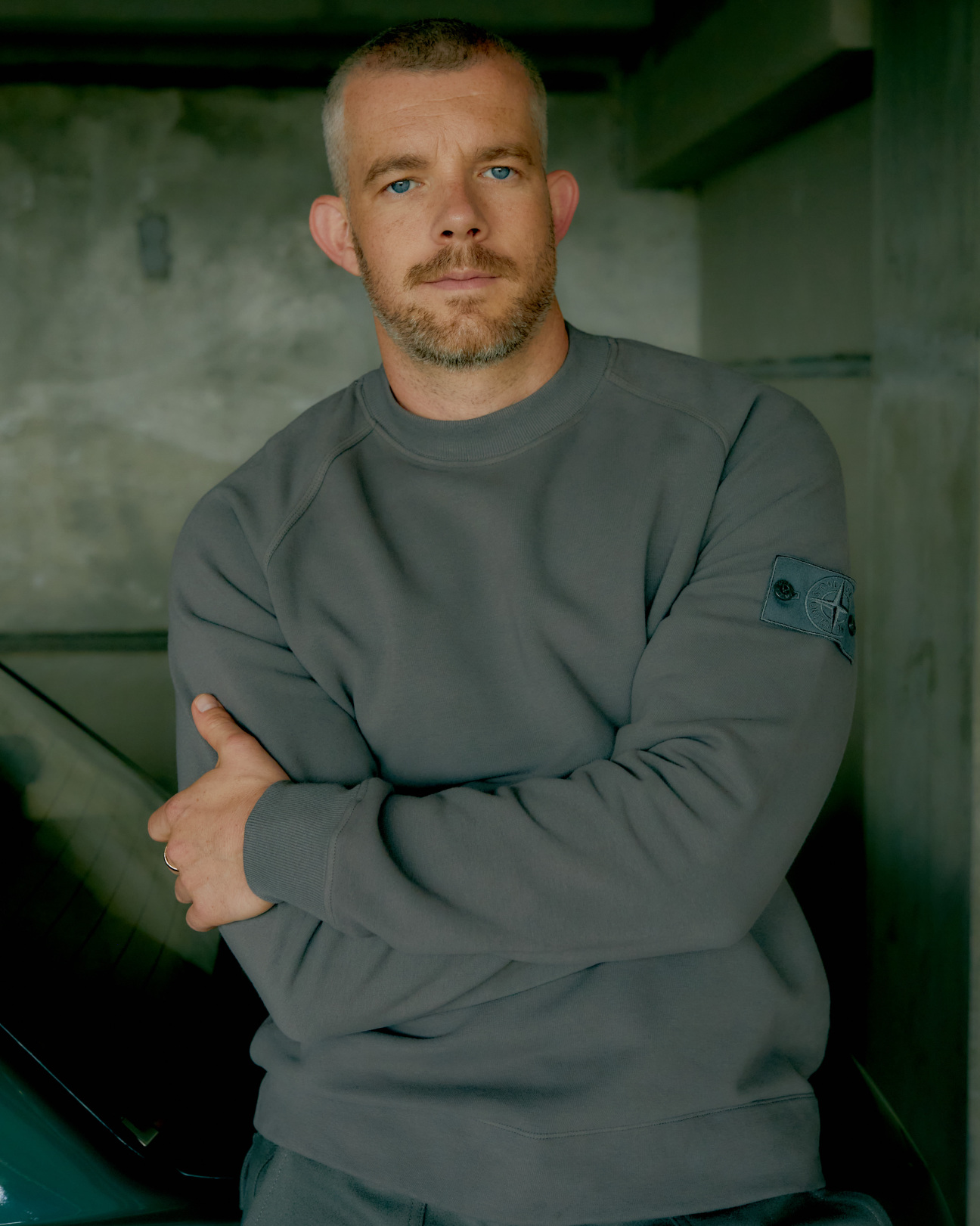

You may know British actor Russell Tovey from his film and TV work. He has played the likes of a werewolf in the BBC show Being Human, Truman Capote’s on-again-off-again lover in FX’s Feud: The Swans v. Capote, and, most recently, a gay man targeted by an undercover officer in Plainclothes, which premiered at Sundance in January. Parallel to his acting career, Tovey has also cultivated a life in the art world as a curator, collector, and co-host of the podcast Talk Art with Robert Diament.

Tovey joined our conversation from the upstairs offices of Mariposa Gallery, where he curated the gallery’s first exhibition in its temporary Los Angeles space. The show, “Peter Berlin: Permission to Share” (through Feb. 23), is the first-ever LA showcase of the influential German artist, who revolutionized queer self-representation and male eroticism in the 1970s.

Tovey and I discussed the evolution of his eye, what visual art and acting have in common, and how he went from feeling like an outsider in the art world to making space for others to find their way in.

What drew you to participating in the art world after finding so much success in film and TV?

I loved cartoons growing up. I discovered Roy Lichtenstein’s comic strip art, saw it on gallery walls, and realized I didn’t need to grow up. When I was 16, I was at college in London and the Young British Artists movement was happening and that changed my life. I understood what the word “contemporary” meant for the first time. I could be around these conversations, which were so inspiring to me as a 16-year-old.

Lichtenstein was also one of the first to draw me into art. I bought something at a local fair inspired by Lichtenstein and used all my piggy bank money for it. Once you get the bug, you get the bug. So, what was your first take on that world? Was it foreign at first, or were you comfortable following your eye?

I’ve been through many phases as a collector. I started buying editions because they were more affordable. When I did a film called The History Boys, I bought a Tracey Emin monoprint, and that was the most money I’d ever spent on anything. It was terrifying. It was a scary notion to follow my instincts because I was hanging around with other collectors who had art advisors, and I felt pressured to collect what they were collecting. It felt like they knew more than I knew. And I ended up with a lot of work that I still have; it’s in storage, but it doesn’t make my heart sing. It was work that I felt I should be acquiring.

I have always been drawn to painting and figures because I’m an actor. I was drawn to body language, facial expressions, the way that humans interact with each other. When I first started collecting, everyone was like, “No one’s collecting figuration anymore. No one’s collecting paintings. You need to collect something that’s made out of Perspex or Chrome.” I went against my instincts, basically.

I can completely relate to that. I worked at a mega-gallery where you are being told there’s a direction. When you don’t feel that connection to the artist, it can feel disassociating. Can you walk me through what you’re collecting now?

The thing that really changed the way I see myself and the way that I collect is queer artists. David Hockney was a big one for me. Seeing David Hockney’s images at a young age shocked me. It felt like a Trojan horse, how they got into the books at school. We Two Boys Clinging Together just blew my mind as a kid. As I got older, I was lucky to be working in New York on a TV show at the time when artists like Doron Langberg, Louis Fratino, Salman Toor, Jenna Gribbon, and Anthony Cudahy were all making figurative, openly queer work that inspired me. I became friends with these people, and I collected their work. I’d always collected Wolfgang Tillmans as a photographer, and I’d always collected the work of Nan Goldin because of the subject matter. Every time I discovered an artist, it was an education. [Through] Nan Goldin, I discovered Cookie Mueller. I now have all Cookie Mueller’s books.

As an actor, as a gay man, I felt a responsibility to shine light on artists [who] deserve more opportunity to be seen. Peter Berlin is still alive, but he represents that generation in the ’80s of post-Stonewall, pre-AIDS, and then he stopped making work around the AIDS epidemic. I think it was quite a traumatic time for him. But Berlin is an artist who has been incredibly overlooked because of the content of his work. These stories are vital—especially in the current climate. It’s important that we don’t forget that time in history.

You’ve interviewed a ton of artists on your podcast, Talk Art. What do you think visual artists have in common with actors?

All art is storytelling, whether it be the visual arts, film, poetry, music, or literature. I’m from a place where the visual arts were othered. The discourse around art was academic and elitist, like a members club with references that I had no idea what they were. But if I didn’t get the reference, then I was locked out. I started the podcast with my friend Rob Diament because I wanted an opportunity to talk about something that I absolutely love, that makes me excited and inspired on a daily basis. We talk to everybody: pop stars, curators, other collectors. People don’t even realize the impact that art has had on their lives. Every time I do a podcast, I think of my mum—I think, My mum doesn’t know any of this, but I want to make sure that she enjoys this episode. She listens to every single episode and gives me a review after each one.

This touches on one of the reasons I left the mega-gallery world in a full-time capacity to start Siren Projects. It’s a club that is nearly impossible to penetrate. I love to help younger collectors feel like there are access points. What other ways can the art world become a little bit more open?

People need to know that it’s for them, and they don’t. So it’s down to the education system. I remember museum trips when I was a kid, but they were few and far between. Art becomes ours when we have the license to critique it. If I said, “Oh, I really like the latest Beyoncé album,” and you said to me, “It’s not as good as the last one,” I wouldn’t say that you were wrong. I would go, “Oh, that’s a valid opinion. It’s not my opinion, but that’s an opinion.” We both can have an opinion because the album’s been given to us as a piece of art that we are allowed to critique. But when it comes to [visual] art, we don’t have the education to critique it.

Movies, TV, and music do feel so much more accessible to people.

From childhood, you are given it. It’s yours to do with what you want. You can say, “I don’t want to watch this. I’m bored.” And people go, “Fair enough.” Whereas if you’re in a museum, and you go, “I don’t like that,” people go, “Oh, you don’t like it? You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

When we were kids, we watched things on our TV or listened to things on the radio. There are access points in our everyday lives, but art is a privilege. It takes a little bit of effort to go see.

And it shouldn’t be a privilege. The people who are making the art want you to see it. They’re not making the art for just a few people to collect it. They want to connect as many people as possible, and they want you in museums. These big cathedrals have been established around this stuff that’s made by humans for other humans to understand what it is to be human.

This week, you’re putting on that curator hat. How does that feel?

It’s a complete privilege because I treat it as if everything in that room is part of my collection. How would I hang it in my house? I’m constantly rearranging my house. I have done this since I was a kid, I would drag my bed to another wall in the bedroom just to feel a different energy and then sleep in it.

Feng Shui.

Feng Shui. It is a definite energy thing. I love doing it, but I don’t feel the pressure of someone going, “You’re a shit curator.” Because I’m like, that’s fine. I’m not doing it to get to the top echelons of curatorial studies. I just want to tell a great story, and I’ll be given these opportunities time and time again now. This is probably my tenth or eleventh show that I’ve curated.

You’re clearly doing something right. Because let me tell you, if you’re not a good curator, they’re not calling you back for a tenth time.

I just love it, and I think you’ve got to love it. I’m obviously not doing it for the money. It’s the same as the podcast. I’m privileged that I have a multifaceted creative life, and I never take that for granted.

I think that that is a beautiful way to experience yourself through other artists—less I-am-the-star and more, How do I elevate other people in order to tell a beautiful story?

I’m a conduit. Half of the people who come to this won’t even know who’s curated it. They won’t give a fuck, they’ll just come to see the exhibition.

Many readers won’t be able to come to the show in LA. Can you tell us about a few highlights?

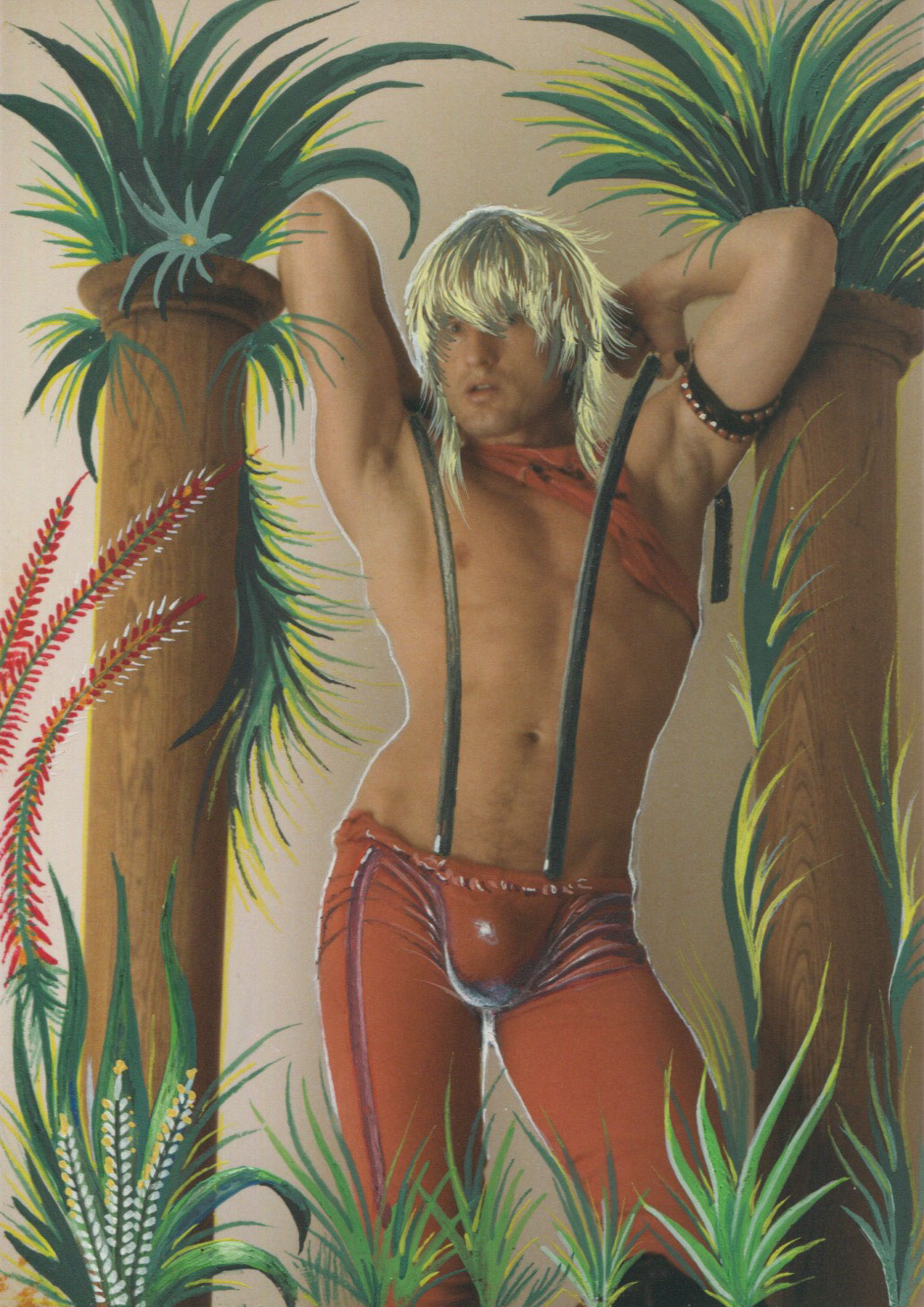

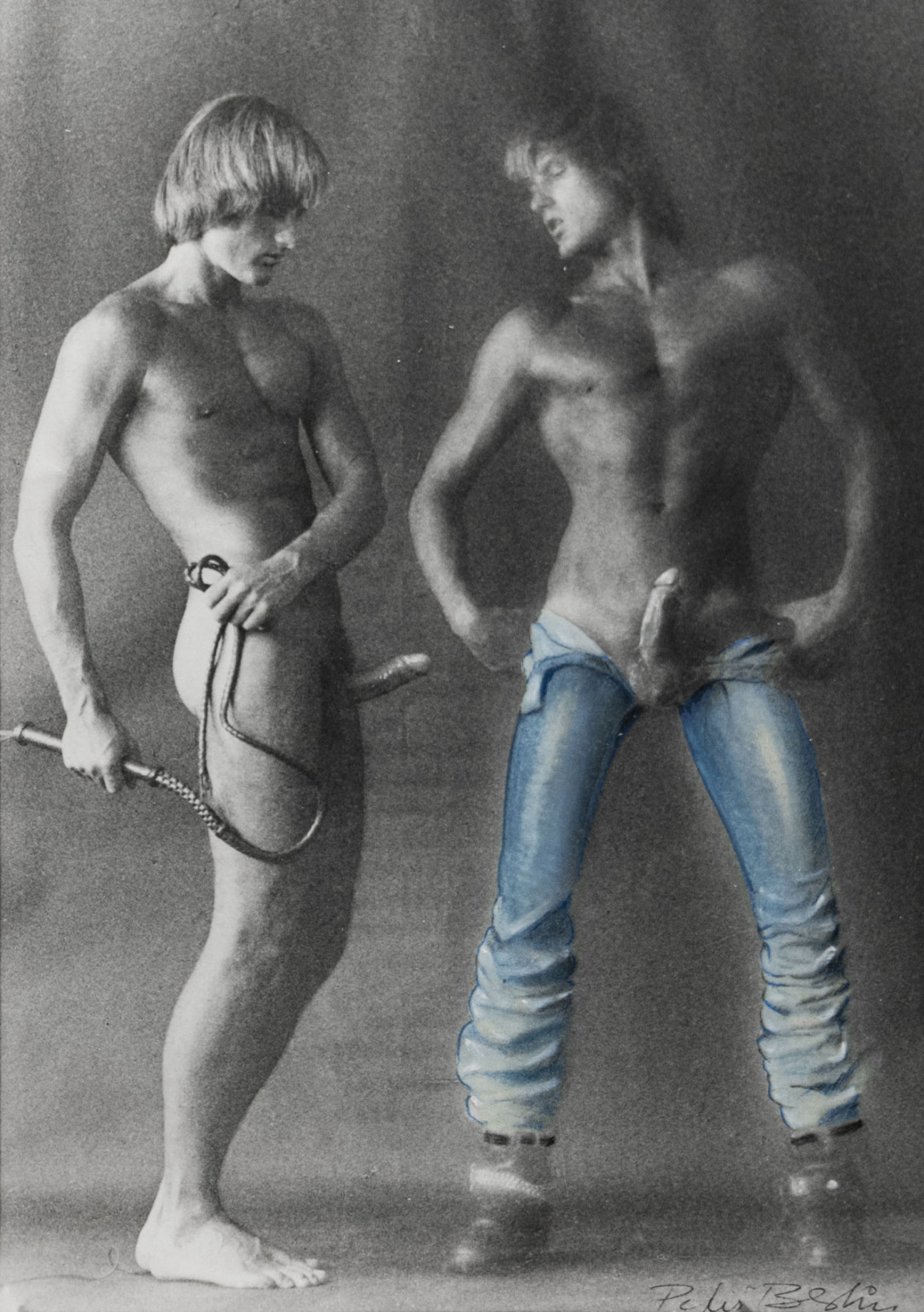

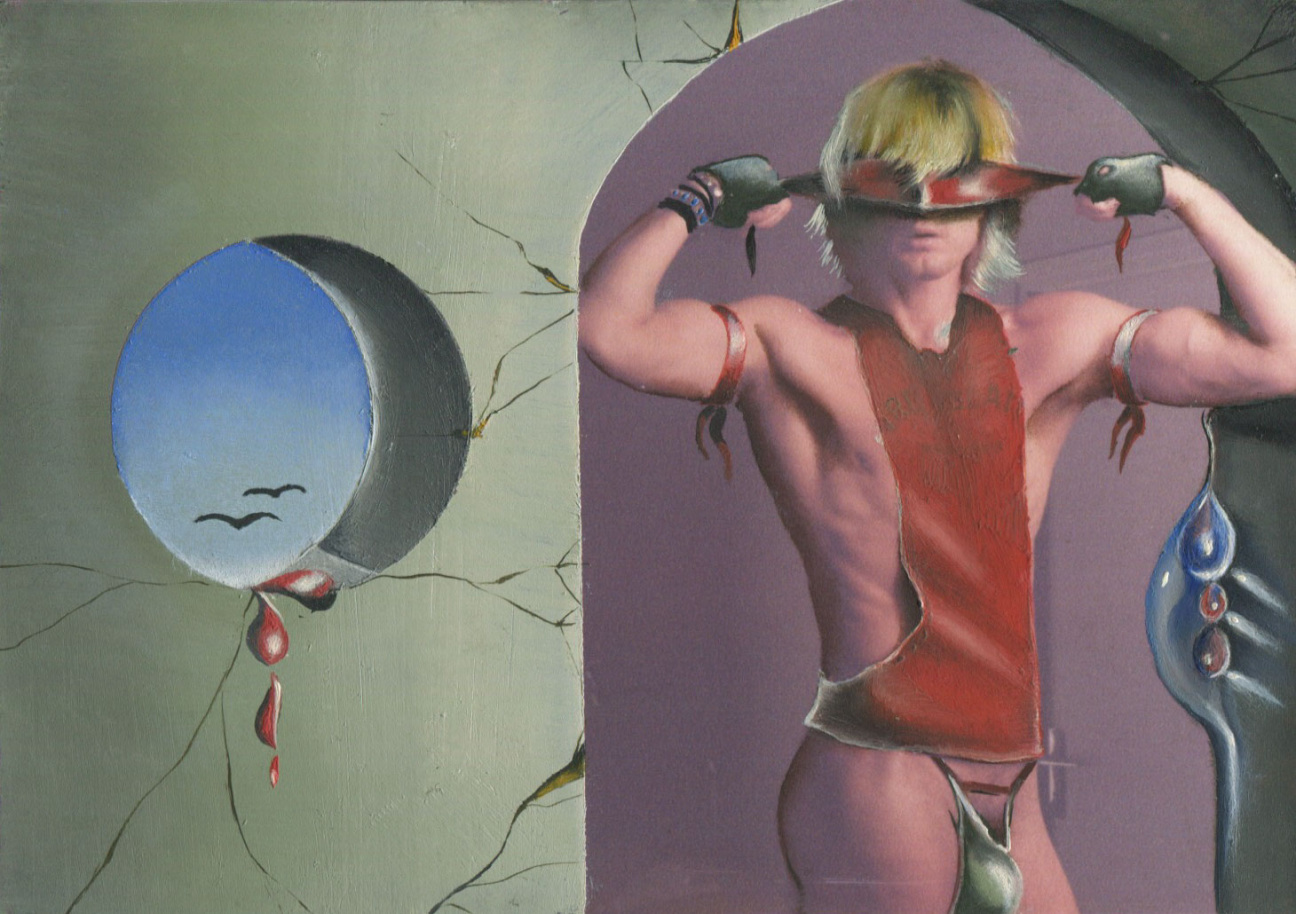

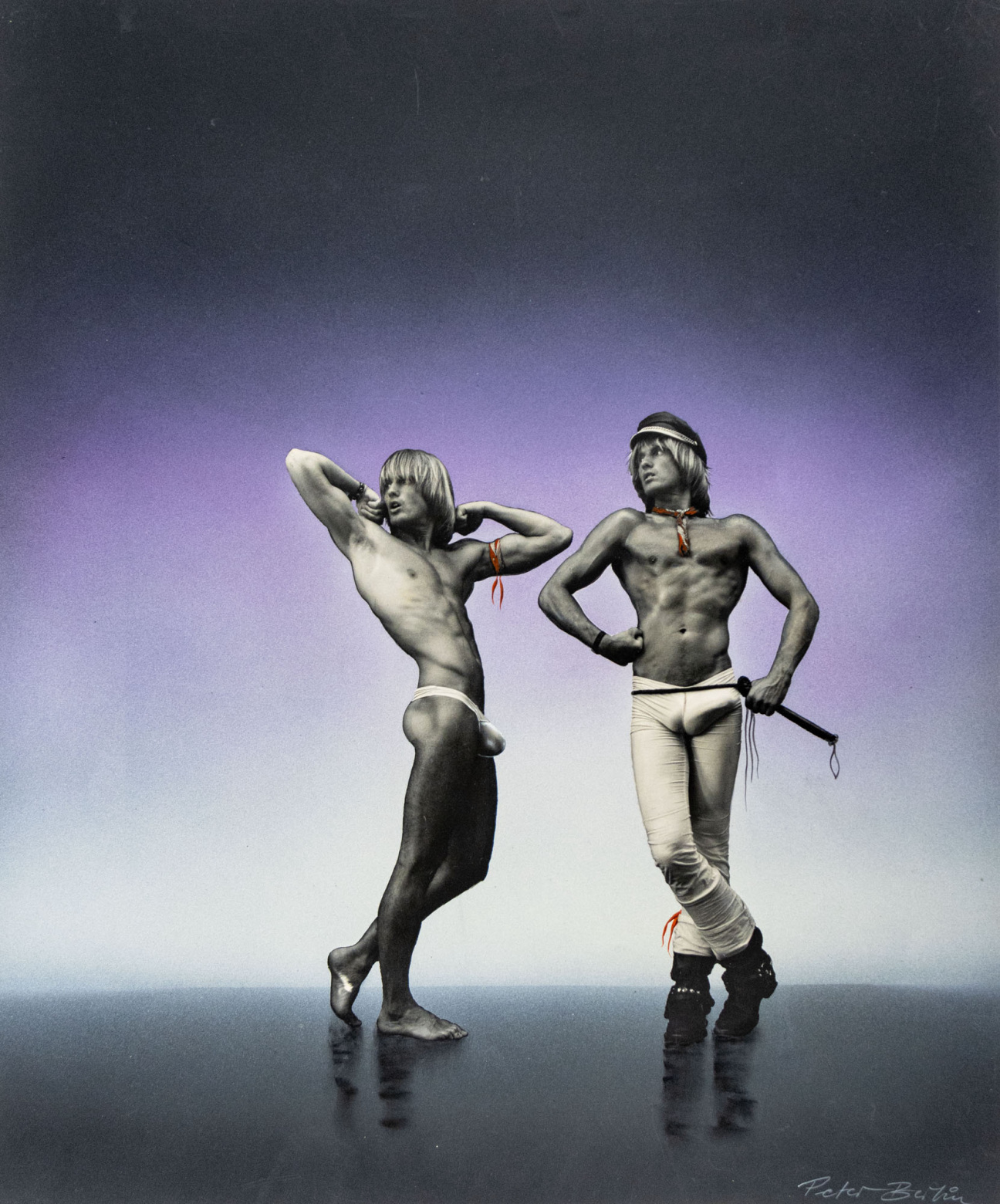

Well, we interviewed Berlin for Talk Art, so there’s an episode coming up. He is 83. He lives in San Francisco. He stopped making the work that we’re seeing in this exhibition in the ’80s. All of his work that we have here [at Mariposa] and the majority of his work is unique. They’re unique photographs that he took of himself. He mastered airbrushing from an artist friend of his, so he would tape out the image and then do these airbrushing techniques so they feel psychedelic. He didn’t want to waste photos. If they came back overexposed, he would hand-paint over them. He would create his own clothing.

We’ve got his clothes here too—boots, little kind of knickers, and all these different things that he wore to go cruising. He represents a time in history when liberation was happening for queer people and gay men especially, post-Stonewall, pre-AIDS. There was a moment in history where it was safe, joyous, and exciting. It’s just such an incredible moment to have immortalized in these images of someone who represents absolute freedom and pride in himself. They’re just mad, and they’re sexy, and they’re uncomfortable.

When I first saw his work when I was a kid, I found it terrifying as a gay man. It scared me in the way that I found Tom of Finland terrifying. I think I was scared because I felt like they made me vulnerable or my community vulnerable because they were exposing and provocative and alien to most of society. But that’s the point of art. It is not meant to be beautiful and calming and something [where] you just sort of go, That’s nice.

Someone once said to me, “When you’re made uncomfortable by art, you should keep coming back and feeling uncomfortable because you can imagine what it took for the artist to create something like that.”

Peter Berlin was a performer. He lived like an artist every day. Even if we went to the shops to get some milk, he would always be Peter Berlin. And I think that’s so incredible.

It’d be like the equivalent of you living in one of your movie characters all the time in order to tap into that.

Yeah—method acting. For artists to make themselves vulnerable and put work out there because they feel this need to communicate is an act of generosity. And then you think of the outside forces in the ’80s—especially [for] artists who were touched by AIDS or who died of AIDS [related complications], like David Wojnarowicz and Peter Hujar—and the pressure that was on them to just exist in society, distilled into these images. These images are vibrating with history.

in your life?

in your life?