The best chefs don’t chase trends; they set them.

The past decade has given Erik Ramirez many a chance to prove himself as deserving of that description. Since debuting the now-beloved Peruvian spot Llama Inn in 2015, the New Jersey native and his partner Juan Correa have opened a total of five restaurants, garnered their fair share of accolades (a handful of New York Times stars and a James Beard nod among them), and built up a legion of devotees who look to their stable of eateries for fare that straddles curiosity and comfort. The newest to join the family is Papa San, Ramirez's riff on a Japanese Peruvian izakaya. On Feb. 18, the newcomer will open its doors on the ground floor of Hudson Yards's Spiral building.

Ahead of the restaurant’s debut, Ramirez sat down with CULTURED to trace his journey from dropping out of culinary school to reinventing Peruvian classics for a New York sensibility.

Where are you, and what's in your system?

I'm home in Brooklyn, and I had a glass of water earlier, a coffee, and a mango.

How do you take your coffee?

Black. I have a coffee shop not too far from where I live, and I used to wake up and get something like an oat milk cappuccino. But I had a bodega coffee, realized how cheap it was, and was like, Holy shit, I'm just gonna have a bodega coffee from now on. It's just about getting some gas in the engine.

I know you grew up in New Jersey to Peruvian parents. Can you tell me what kind of eater you were as a child?

I grew up in Passaic, New Jersey—predominantly Latino with tons of Peruvian restaurants. There's a [nearby] city called Paterson which has the second largest Peruvian population in the world per capita. My parents both migrated to New Jersey in the late ’70s, so I grew up in a very Peruvian household. One of my favorite dishes was lomo saltado, which is like a beef stir fry. We would usually go out to eat on Sundays to a Peruvian restaurant, typically for chifa, which is the Chinese Peruvian blend. I would always pick out the onions and tomatoes and just eat the meat with the sauce—and the french fries and rice. So I do think I was kind of picky, but as I grew older, my palate started expanding and I started eating everything.

Do you remember the moment when you started wanting to spend time in the kitchen?

I was out all the time. I liked being outside and hanging out with friends, getting in trouble and stuff like that. But at some point, my mom was like, "You gotta figure something out. You can't stay around here or you’re gonna get in trouble. You're gonna go stay with your uncle for the summer." He lived in Grand Isle, which is a little island on the tip of Louisiana, where it's super Creole and very southern. He worked offshore on oil rigs, but he was an avid cook. For my mom, cooking was just like going through the motions. She would definitely put love into it because she was feeding her family and everything, but my uncle made it fun. He'd say, "Hey, let's barbecue. Let's bake some bread…"

So he was definitely the influence that made me think of trying culinary school. I went to the Institute of Culinary Arts in Philadelphia, a super affordable program. I dropped out of high school my sophomore or junior year. I went to the culinary school and didn't finish there either. But I got into a really good restaurant in Philadelphia and worked with really good people.

At what point do you move to New York?

After a few years. I started at this little French bistro called Frederick's Madison. Months later I got into Eleven Madison Park. I had worked at fine dining places in Philly, but EMP was on another level. I stayed there three years as a sous chef, then left and went to Irving Mill as the chef de cuisine with one of the chefs from EMP. So for the first 10 years of my career, I cooked American, Eurocentric food—never Latino food. I just looked at it as the food I grew up eating. But then I took the job at Nuela. I was skeptical because it was nuevo Latino, and I wasn’t too familiar with [cooking] Latino food, but then I met Adam Schop. He became the executive chef, and I became a CDC. I fell in love with the guy; I had really good conversations with him. So I stayed there two years, but the restaurant was a disaster. It got really bad reviews. The design was really bad. The owners were this Colombian family. Armin Torres and his wife Mary really took me in. They made me feel like family. Armin was like, "Look, let's close this place and open a Peruvian place. I want you to be the chef."

But I didn't know anything about Peruvian food at this point. I was probably 30 or 31. I was considering moving to San Francisco because my girlfriend at the time got a job there, but Armin just kept at it. He told me, "Go to Peru, and see what they're doing." I would go visit regularly because my grandparents were there. My grandmother was an amazing cook, and their neighborhood always had these little street vendors that were really, really good. But now I was going to Peru more with more of a professional [focus], looking for answers. And I was completely blown away. It was like they were cooking as if they were in New York, but using Peruvian ingredients. The flavor was potent—acidic, sweet, salty, spicy—and presented in a very composed and complex way, as opposed to more technical fine dining. I came back and was like, Man, that was an amazing, amazing experience, with ingredients I've never had, flavors I never had. I think I want to give this a shot. So then we decided to close Nuela, and I went back to Peru for about a month to cook at different restaurants. That's how I made a good network and a lot of friends, which to this day I'm still in contact with. They've all been very supportive of what we've created for Peruvian food here in New York.

And then Raymi was born.

Yeah, Raymi is where I learned a lot through a lot of trial and error. My sous chefs were Armin's two sons. I had Peruvian cooks and prep cooks that were also very helpful in guiding me. Everything was going well, and then my partner now—Juan Correa—reached out through LinkedIn. He was like, "Look, man, what you're doing is pretty cool. It's different from what you can find in New York, Peruvian cuisine wise. Would you be interested in having a conversation?" That's how the Llama Inn concept started. The idea was to give Peruvian cuisine a platform, but in the form of a restaurant that people were familiar with. I didn't want to be pigeonholed in this box of doing traditional Peruvian food. I wanted New York to be the backdrop. The art, culture, the freedom of interpretation, the ingredients, the seasons—all that coupled together with my knowledge of Peruvian cuisine, being Peruvian, that was Llama Inn.

Tell me about the DNA of your newest spot, Papa San. How do you keep challenging yourself with each new restaurant?

I didn't know anything about Nikkei cuisine, so the whole process of my third restaurant [Llama San] was very uncomfortable. I was out of my comfort zone. And the same with Papa San. It's a Peruvian izakaya. We wanted the vibe and the mood in the traditional sense of what an izakaya represents, but we're reinventing it because I've never put together an izakaya menu. So we're gonna start here, we're gonna see how people are receptive to it, what people like. It's a learning process—I adapt.

I also feel like things have become so expensive lately. With this wave of restaurants that are opening up, it’s like you’re going to this beautiful place, but the food is kind of an afterthought. I want something that people are comfortable eating. I want accessibility. I want people to be able to eat there every day. I want them to have a good experience and not walk away thinking, I just spent so much money on like four dishes. I want people to have fun and drink and eat, and I don't want people to feel uncomfortable ordering things on the menu because they're not familiar with it.

Zooming out a bit from your own restaurants, what do you want to see more and less of in the New York food world right now?

Something [I’d like to see] is a little more recognition for ethnic and Latino restaurants. I feel like the market is flooded with American and Eurocentric restaurants. It's a lot of the same, and I'm not trying to be disrespectful, or talk bad about them. It's just that there's an oversaturation. How many more Italian restaurants [do we need?] You had this wave of Korean restaurants opening, so that was on trend. Now you have this wave of French restaurants opening. It’s a cycle. I'd like to see more Peruvian restaurants open, but it's difficult because there's not a lot of people like me. I grew up here. I was exposed to the New York market. I'm Peruvian, but I'm also American, so I understand how we cook here and eat here. How do we keep moving Peruvian cuisine forward?

What other restaurants in New York are you most excited about right now?

I'm a single dad. I have two boys, 10 and 8, so going out to eat is difficult. But a restaurant that I recently ate at that I thought was pretty great was Sailor, April Bloomfield's restaurant. I really want to go to Bridges. I want to check out Theodora, because I think Miss Ada is a great spot. I definitely wanna check out Coqodaq to see what the hype's about. But my spots are the spots in my neighborhood, like my buddy's restaurant in Williamsburg called Ammazzacaffè or Daphne's in Bed-Stuy.

You mentioned your bodega coffee. What's your go-to bodega order?

I get a bacon, egg, and cheese with salt, pepper, and ketchup on a roll for my sons sometimes. Or I'll buy bananas to make smoothies.

What dish represents where you are in your life right now?

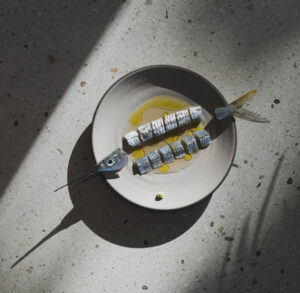

The eel pizza at Papa San, because that was one of the first dishes that started this conversation.

in your life?

in your life?