When Carol Cole Levin thinks about the South, a few things come to mind: dark humor, self-deprecation, and bluegrass music. She speaks about her adopted home of Greensboro, North Carolina—where she moved in 1984 looking for good art and an even better public school for her son—with distinct affection. More than 40 years later, the artist, philanthropist, and collector is giving back to the community with the Cole Levin Center for Art and Human Understanding, funded by Cole Levin’s recent gift of nearly $5 million to the Weatherspoon Art Museum at UNC Greensboro.

This center is the latest iteration of Cole Levin’s work with the institution, which includes serving as president of the advisory board and a show of her own surrealist drawings and mixed-media sculptures, alongside collected pieces. The Cole Levin Center will exhibit works from her collection in a study center on the first floor of the Weatherspoon, and will be used by UNCG students, half of whom are first-generation college students. Humanist inquiry is the focal point of the new space, and this spring, the students themselves will be curating the center’s exhibition.

Following the announcement of Cole Levin’s donation, the collector sat down in conversation with CULTURED to offer an inside look at the collection she’s shortly putting on view, as well as the pieces she’s kept for display in her own home. Here, she reflects on her deep ties to Greensboro's vibrant art scene and the artists she’s been able to bring into this off-the-main-drag locale.

1994. Lower left: Suzanne McClelland, Home of the Brave, 1998. Photography by Dhanraj

Emanuel.

How do you hope to help shift the Greensboro art scene with the creation of the Cole Levin Center for Art and Human Understanding?

I moved to North Carolina in 1984 after choosing to leave Mississippi but wanting to stay in the South. I hoped to find a place where I could enjoy contemporary art, work in software as a woman, and give my younger son a good public education; I found them all in Greensboro. There’s a sense of support here for people doing what they want to do, and I think that permeates the arts as well.

I don’t have any desire to shift the art scene. What I want to do is bring more people into it. I hope to open people’s minds to visual art with psychological depth and vulnerability, work that might offer us insights into ourselves and others. And I also want to encourage people to think about the connections between the visual arts and other arts. I’m interested in the richness of Southern culture: dark humor, laughing at oneself, playing dumb, blues, bluegrass, literature, theater, self-taught artists—and so much more.

Where does the story of your personal collection begin?

I purchased my first painting in 1976. It was by Tom Askman, who was teaching art in Thibodaux, Louisiana, and was in a group show at the Masur Museum of Art in Monroe. At the time, I was painting in the carriage house of the Masur with a group of women who used it as studio space. Askman was influenced by the Hairy Who and the Chicago Imagists, and I loved the humor in his imagery.

Not long after, in 1979, I had to give up making art because of a divorce and the need to make a living to support myself and my two sons. I didn’t start making work and collecting again until the early 1990s, after relocating to North Carolina, building and selling my software business, and getting remarried. At that point, I started buying work by the artists who had mentored me in the ’70s, like Ida Kohlmeyer and Lynda Benglis. I wanted to collect their work in appreciation for the nurture and encouragement they provided.

Which work in your home provokes the most conversation from visitors?

What surprises people the most is how many images of breasts I have! To me, the breasts aren’t sexual but are symbols of nurture. That’s the most important theme in both my collecting and my own work. We all need nurture. Whether we are young or old, female or male, we all need care and somebody to believe in us.

Which artist are you currently most excited about and why?

There’s no single artist. I get most excited by having the chance to introduce artists from other places to our community here in Greensboro. Working with the Weatherspoon over the years, I’ve been able to help host such artists as Judy Pfaff, Lynda Benglis, and Pepón Osorio, who have come to meet with students and give public talks. I always especially love the chance to share my collection and hear their reactions. We are soon to host Saya Woolfalk (whose work is in my collection), and I’m eager to learn more about her current projects.

What factors do you consider when expanding your collection?

I am no longer expanding my collection. At this point I’m trying to place it in museums. I have never sold a work from my collection—collecting has always been a part of my own artistic practice. None of the art was purchased as an investment, each piece has a soul, so I am very thoughtful about where they will go.

Do you collect anything other than art?

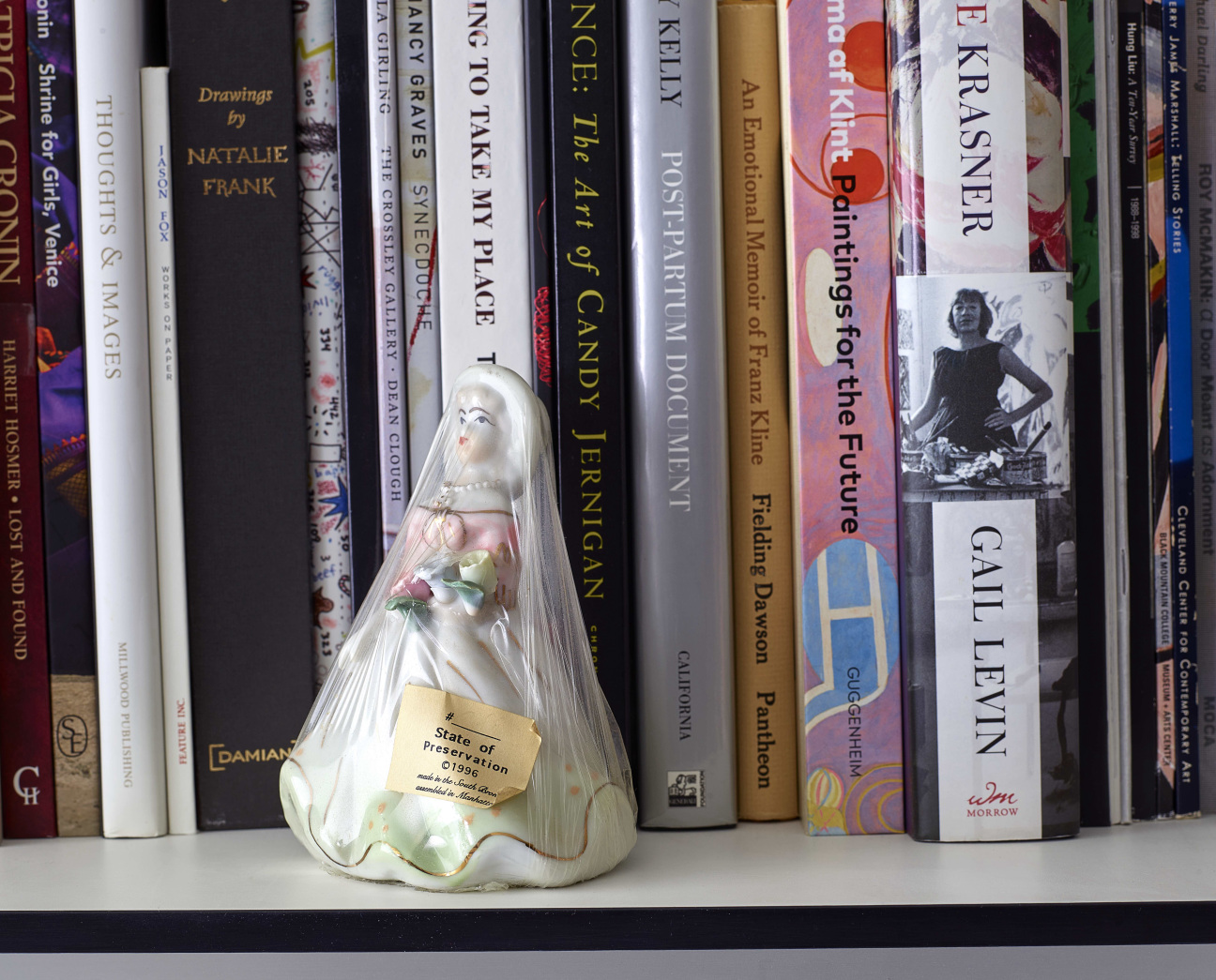

I also have a book collection. It’s full of artist monographs, exhibition catalogues, art history books, literature by Southern writers, cookbooks, and books on mental health and art therapy. There are lots of feminist themes throughout.

What is the strangest negotiation you've ever had with an artist or dealer?

What comes most to mind in terms of purchases are meaningful connections with artists. In the ’90s, I attended a workshop at Anderson Ranch with Arlene Raven, the feminist art critic, and I met her partner, sculptor Nancy Grossman. Nancy’s zippered leather heads had been a strong influence on me after seeing images in Cindy Nemser’s book, Art Talk, in the ’70s.

She was on my list to collect, and I knew she didn’t have a gallery in New York at the time. After the workshop, I arranged to visit her loft in Chinatown and purchased one of her zippered leather heads that was very autobiographical and vulnerable. Years later, artist Trenton Doyle Hancock visited my art and collection, and the first thing he said when he walked into my living room was, “That’s the best Nancy Grossman I have ever seen!”

in your life?

in your life?