The businesses of fashion and media are uneasy bedfellows. Yet the two industries have never been more closely intertwined than they are today—and the fate of fashion criticism hangs uneasily in the balance. Sea changes in media make for a daunting vista: Fast fashion’s behemoth environmental impact, a dearth of representation (gender or otherwise) among high-profile creative directors, and the proliferation of self-styled tastemakers have monopolized online discourse.

Add to the mix a staggering concentration of power: Many of the oldest and best-respected legacy labels are nestled under the wing of titanic conglomerates, and many a publication is reliant on the partnership of those same companies to remain afloat. In 2025, neither industry can be said to boast a clean bill of health. Where, in this thorny new landscape, does the role of the fashion critic lie?

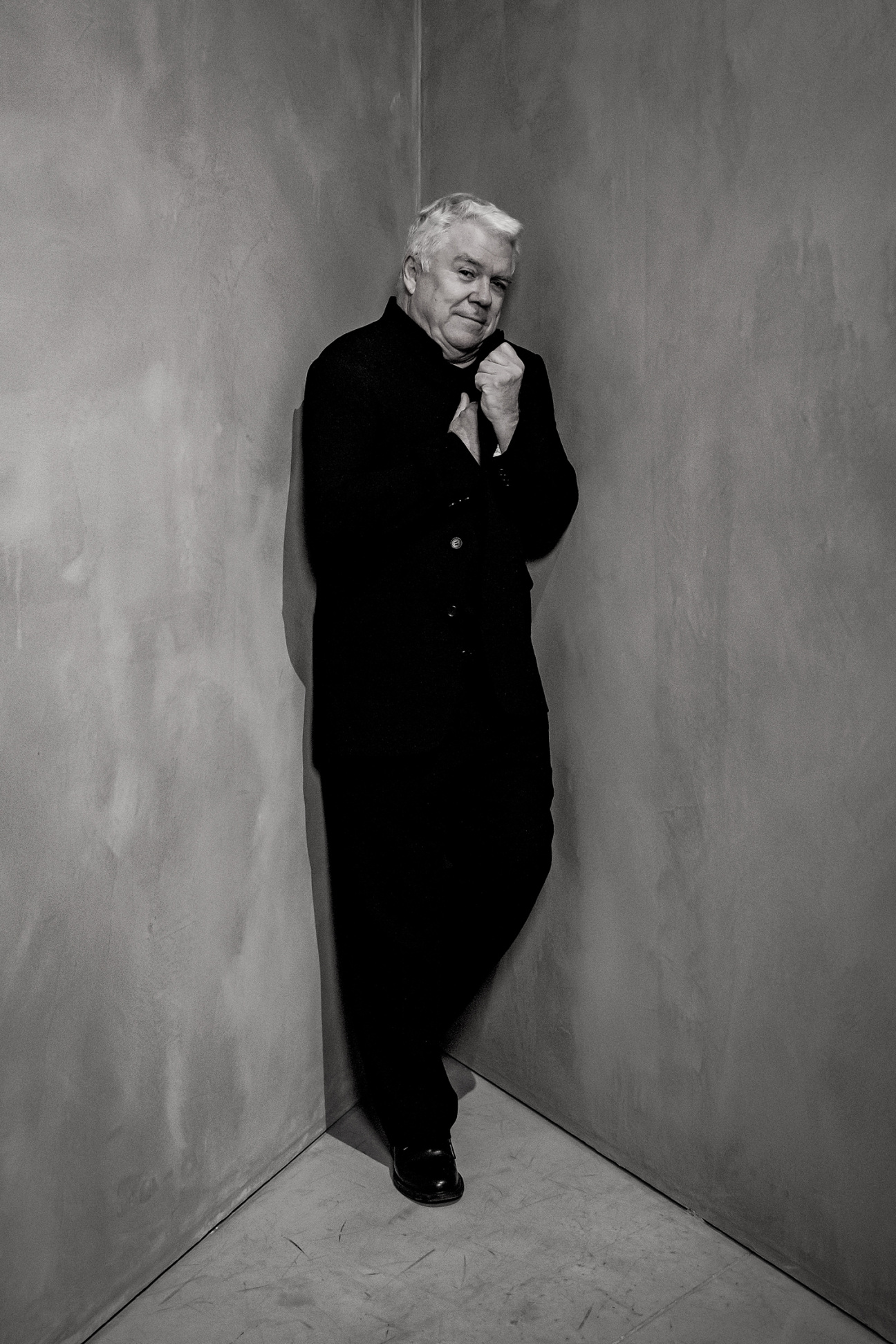

To answer this question, CULTURED convened three of today’s leading voices for a candid roundtable discussion. Tim Blanks, a front-row fixture who has been covering the fashion world since the late 1980s as a TV host and writer, is editor-at-large of the industry bible Business of Fashion. Vanessa Friedman became the first-ever fashion editor of The Financial Times in 2003 and, for more than a decade, has served as the formidable chief fashion critic of The New York Times. Rachel Tashjian made her name as GQ’s first fashion critic and founder of the cult shopping newsletter Opulent Tips before landing the coveted position of fashion critic for The Washington Post in 2023.

This trio reminds us that good fashion still exists, and that a good designer holds a mirror to surreal times—tectonic political shifts, evolving social mores, and quotidian delights in equal measure. Blanks, Friedman, and Tashjian have each earned reputations as canny ciphers of this undertaking, interrogating and forging connections between a disgraced billionaire’s courtroom wardrobe, a legacy brand’s earnings, and the most subtle semiotics of power. Here, they suggest that the role of the critic might be surprisingly timeless after all—at least within established media organizations. Look, contextualize, translate. Repeat. —Mara Veitch

Julia Halperin: What drew you to fashion in general, and fashion criticism in particular?

Tim Blanks: I grew up in New Zealand. There was no fashion. Music was my passion. David Bowie would wear extraordinary clothes by Kansai Yamamoto, so I had a sense of what fashion could mean and do. I ended up in Canada editing a fashion magazine and covering shows—not critically, but descriptively. Then I went to Style.com and started reviewing shows.

Vanessa Friedman: I came to fashion mostly through journalism. During a freelance period in my life, I started getting assigned fashion stories and ultimately realized that fashion was an incredible prism for talking about almost anything a journalist or critic could want to discuss. Fashion is the ultimate Trojan horse. It allows you to explore questions of identity, politics, culture, and news.

Rachel Tashjian: It’s funny, I think we all have similar stories on different timelines. I was always interested in music and obsessed with Rolling Stone. I liked vintage clothes and what Janet Jackson and Britney Spears wore. I read a lot of fashion journalism, much of which was written by Vanessa and Tim, [but] I didn’t feel Vogue was for me. After college, everyone was starting fashion blogs, which was a way to get into writing. Early fashion blogs were often about fashion through the lens of film or art, which opened the world of clothes to me.

Halperin: What’s the biggest difference between covering fashion now and when you started?

Friedman: The New York Times didn’t have an official fashion critic until 1994. The Financial Times didn’t have a dedicated fashion page until 2003. More people are interested in fashion now, and it’s part of pop culture in a way it wasn’t before. But I don’t think the actual work of fashion criticism has changed much.

Blanks: I agree. In Toronto during the ’80s, the dailies had fashion supplements, [but] fashion criticism didn’t have the cultural weight of art or music criticism. Rolling Stone or Melody Maker could inspire people to buy records or see movies. Critics like Clement Greenberg changed art by writing about it in newspapers. But in fashion, there weren’t critics who could shift public perception in the same way.

Friedman: The role of a fashion critic is different. It’s not about saying, “You must have this handbag.” It’s about helping people think about their relationship to clothing differently.

Tashjian: Fashion critics have a different relationship with their subjects. I focus on the reader, not the designer. But designers often respond directly to criticism, sometimes negatively. I’ve seen designers post about things Tim, Vanessa, or I have written. I don’t see that same dynamic in art or music criticism.

Blanks: Really?

Tashjian: Yeah. Dance or opera critics often write about works whose creators are long gone.

Friedman: If you’re talking about [former Ballet Master] Peter Martins at New York City Ballet, I don’t think that’s that different from talking about Maria Grazia [Chiuri, creative director of womenswear] at Dior, right? They’re there to steer, reshape, and interpret an existing institution.

Halperin: When you write a negative review, what impact do you want it to have?

Tashjian: I don’t really think of my reviews as negative or positive.

Blanks: Have you ever had anybody say to you, “Oh, I really thought about what you said, and I’ve addressed it in this new collection. I hope you can see that”?

Friedman: I had Marco Bizzarri, when he was CEO of Gucci, give an interview to Corriere della Sera. They asked him what he thought of critics, and he went on this rant about how irritating I was—how annoying my reviews are, how I couldn’t say something was good without pointing out the issues at the same time. And then he said, “But when I think about it, she’s usually right.” He sent it to me. I said I was going to put it on my gravestone. But that’s pretty rare.

Tashjian: I called [Schiaparelli Creative Director] Daniel Roseberry “the meme weaver,” and for one or two seasons after that, he gave interviews saying, “I’m not going to be the meme weaver anymore.”

Friedman: Daniel quotes you back to you all the time. It’s kind of smart.

Blanks: They all do.

Tashjian: How could you not? I mean, I read all my comments and letters.

Friedman: I still don’t read all my hate mail.

Halperin: Do you consider yourself someone who has power in the fashion industry?

Blanks: I think there was a golden age at Style.com [where Blanks was editor-at-large for 10 years] when fashion criticism possibly existed as an actual force for good—or as a force, anyway. But I don’t think that applies much anymore. Everybody’s a critic now.

When A.O. Scott left The New York Times, he was asked about the role of the critic. He said he never thought of himself as an expert or authority. He thought of himself as a companion. I’d like to think I’m conveying the experience I’m having to people who aren’t there. That’s always been my goal.

Friedman: The New York Times has power. The platform has power. That’s different from me having power.

Tashjian: There’s a funny thing happening now—a fashion fake-news problem. Friends of mine who work in related industries will say, “Oh, I saw this social media post that Jonathan Anderson is going to Dior. Isn’t that great news?”

As someone who works at a newspaper, I find it curious that there’s this conferred authority on accounts with just a couple hundred followers. There’s so much excitement to contribute to the creation of news, whether it’s true or not.

Blanks: Don’t you think fashion has a unique ability to make people want to be part of the dialogue? They hear, “Hedi Slimane is going to Gucci,” and suddenly they think they’re in the know. Fashion trades on this fundamental insecurity. It’s always been a very gossipy industry, and now more people know about it, so there are more people gossiping.

Halperin: How do you balance covering fashion as an art form, as a business, and as something every human being puts on their body before leaving the house?

Friedman: You have to go into these jobs with an awareness that different stories are for different parts of the audience. There’s a core fashion audience who cares deeply about designer changes and runway happenings. Then there are people who don’t, but they care about what Melania Trump is wearing or what’s happening at the Golden Globes. And there are others who care about the latest knit bonnet on Instagram. You have to try to please as many people as possible and then deal with the whiplash, especially during times when you’re jumping from the inauguration to couture.

Blanks: Do you think there’s a thread between all these audiences? Something about fashion that creates a slightly more homogenous constituency?

Friedman: I think so. The essential approach is the same: How is the clothing being used as a tool to communicate?

Blanks: I’ve always come at it as a human interest thing. When I was doing the TV show [CBC’s Fashion File] years ago, I thought, What an underexploited trove of incredible people and stories. My reviews over the years have morphed into profiles. When we started Style.com, [Founding Editor] Jamie Pallot said nothing should be more than 200 words. Then Nicole [Phelps, the executive editor] and I started writing pieces up to 1,500 words, sometimes three or four in a night—not bad going.

Tashjian: Covering fashion makes you see the world differently and ask, “What’s the fashion story in this piece of news?”

Friedman: One difference now is the appetite for that kind of coverage. Twenty years ago, if I’d said to the Times, “The confirmation hearings are a fashion story,” they would’ve told me I was nuts.

Tashjian: The proliferation of fast fashion has also made more people feel like they can participate. I was reading Vanessa’s piece about Pete Hegseth [Donald Trump’s newly confirmed U.S. secretary of defense] wearing an American flag pocket square during the confirmation hearings. Twenty years ago, if you wanted an American flag-lined jacket, you’d have to go to a specialized tailor. Now, brands like Fashion Nova or Shein allow people to dress like Charli XCX. That accesibility makes consumers, critics, and participants overlap—you can be all three at once.

Friedman: Big fashion brands have extended their influence to all levels of culture and economic status. Even if you’re not buying the Dior bag, you’re seeing it, talking about it, and forming an opinion. That didn’t happen as much a couple of decades ago.

Blanks: Fashion became part of the entertainment industry in the early ’90s—it’s show business now. That’s made it a great and often delusional communicator.

Halperin: You can’t talk about how people interact with fashion without mentioning TikTok and Instagram. How do you view that digital content compared to what you do? Do you see it as criticism?

Blanks: I’m fascinated by how young people want to explore history and ask questions about old shows. The younger the audience, the more interested they seem to be. But [digital content] is a language I don’t speak fluently. I tried to create a TikTok dance once—it didn’t go well.

Tashjian: I talk very often with people who do Instagram criticism. The common theme often seems to be, “I started this because I really wanted more honest, brash commentary. And then I found the more that I did this, the more complicated it became. I couldn’t just say, ‘This is the worst collection ever.’” Good criticism is never simply saying something is good or bad. There’s a difference between commentary and criticism. Some social media commentators are doing a form of criticism. But most often, to me, it seems like commentary, which is still very valuable.

Halperin: How would you describe the difference?

Blanks: And what would you rather read?

Tashjan: Well, I’m biased. I’d rather read criticism. To me, the difference is context, authority, and expertise. I find that the more I interview designers, the better my criticism becomes. Of all people, [fashion designer] Wayne Diamond, the kind of sleazy guy [who played a version of himself] in Uncut Gems, told me, “Being a writer is so great because it’s the only artistic medium where your work gets better as you get older.” I think it’s absolutely true.

Halperin: You all have full-time jobs doing this, but that’s increasingly rare. How are the precarity of the media world and the rise of independent newsletters changing fashion criticism?

Friedman: I feel like it’s similar to when everyone said, “Blogs are coming; this will change everything forever,” and it didn’t actually change as much. Criticism as a form has existed for centuries, whether it’s fashion or not. I hope that will continue to be true. I just think it goes by many names, maybe.

Blanks: Do you ever hear your voice saying things you’ve said many times before and feel that your response has become slightly hidebound?

Friedman: It’s when you start realizing you’re using the same phrases a lot. But I think that’s a problem with most journalists’ writing.

Halperin: When was the last time you saw something that made you genuinely excited or gave you a jolt?

Blanks: I was just so excited by Alessandro [Michele]’s [debut] Valentino show. I loved the layers of it, the mystery of it.

Tashjian: I get it every time I go to fashion shows, honestly. Not to sound naive, but I’m 36 years old, and I can’t believe that in the media industry we live in, I was hired as a fashion critic at a newspaper. But the last time I felt that jolt was the Alaïa [Winter/Spring 2025] show at the Guggenheim. It was this incredible unwinding of bizarre silhouettes in a really catty room of people sitting on these sleazy chairs. It was fantastic.

Friedman: There’s always something that will make you think. But we see hundreds of shows, and some you forget as soon as you walk out. I thought the last Loewe women’s show was really, really good. I thought Willy Chavarria’s show was really good. That’s what keeps you going.

Blanks: Things do feel different now. I think gigantism really spoiled fashion in a number of ways.

Tashjian: But I also go back and reread Robin Givhan’s columns, my predecessor at the Post. I read a piece from over 20 years ago, a review of Milan Fashion Week, and the lede was, “What a disaster.” So, while there may have been more amazing shows before, I think there was also more boredom and waste than we might remember.

Friedman: That was when designers had time. They had time to have crazy ideas and experiment. They weren’t responsible for the same numbers or the sheer amount of employees. Everything has become so globalized and corporatized now that it’s completely changed the demands on them.

Blanks: And it’s exposed some of the mythmaking—the magic is a bit Wizard of Oz–like. People know about CEOs, COOs, CFOs, and CMOs.

Tashjian: I was rereading a piece in The New Yorker about Marc Jacobs starting at Louis Vuitton. What struck me was the level of access—a journalist sitting in the room as Marc openly said, “I don’t really know what I’m doing.” Now, you’re not handed that kind of access anymore. Maybe I’m being a naive millennial optimist, but I find that exciting. Things are harder, but doesn’t that make it more fun?

Halperin: What do you think fashion historians and critics of the future will say about the 2020s?

Friedman: There’s incredible opportunity. There’s so much change in fashion now—creative power is shifting, and who’s at the helm of big brands is changing. That creates space for someone to think differently about how we dress, express identity, and what it means. I really hope it happens.

Halperin: Do you think it can actually happen, given the corporatization and extreme apparatus you’ve described?

Friedman: I think it can happen. It just takes bravery.

Blanks: Bravery and a love for what you do—not because it will make you a billionaire. I’d love to see independent retailers flourish again, selling independent designers. That’s how people shopped in the ’80s and ’90s in New York and London.

Friedman: I often ask designers and CEOs how big they think they need to be. Almost no one answers. Once, the CEO of Harry Winston told me, “Fifty stores globally, and I’m good.” That impressed me. It’s usually like the Supreme Court’s definition of pornography: “I know it when I see it.” But young designers need to ask themselves that question.

Tashjian: This proliferation of shopping newsletters often points people to smaller brands. It’s an interesting sign that people are intrigued by what exists beyond the big three or four names we always hear about.

Blanks: Restoring the thrill of discovery. But it’s the same with everything—books, magazines, music. It’s all about expressing who you are through the choices you make. I hope optimism is coming back into style.

in your life?

in your life?