Feliciano Centurión

Ortuzar | 5 White Street

On view through February 8

Before he died of AIDS-related complications at the age of 34, in 1996, the queer Paraguayan artist Feliciano Centurión produced a powerful body of work about the inexhaustibility of good faith, that order of generosity with which you—or I, or we—might call upon when bracing for some unknown future. For the works in the riveting exhibition “Sol naciente” at Ortuzar, Centurión used paint, collage, and an Indigenous lace technique called ñandutí, embellishing the hairy, pre-patterned surfaces of frazadas (blankets) and other mass-produced textiles with stars and stripes, creatures from the Paranaense Forest where he grew up, and gutting phrases that feel both fresh and old as time. The piece Que en nuestras almas no entre el terror (may fear not enter our souls), 1995, is composed of a placemat-size fragment of a shipping blanket, embroidered with the artist’s blessing in red. The script of the show’s exquisite title work appears in a tiny cosmos of floral orbs.

Centurión grew up in rural towns during the military dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner, living with his mother and grandmother, who taught him to sew. After his family moved to Argentina, he attended art school in Buenos Aires, joining a group associated with Centro Cultural Ricardo Rojas (El Rojas). The 26 works assembled here limn Centurión’s dislocated position as a migrant within this elite artistic milieu; he was the queer exile, unafraid of kitsch, who unabashedly doubled down on subjects already laden with cultural associations, such as the solar orb of the Argentine flag, the martyred body of a saint, and the Eye of Providence (the disembodied organ in a radiant triangle, as seen on the back of a one dollar bill). Also on view is the bestiary of Centurión’s "Familias" series, c. 1990, plastic figurines dressed in crocheted outfits—one, a serpent in a turtleneck, emerges from a pink plastic vessel; another, a fiery-eyed Godzilla, models a lemon sweater dress. The animals bear their fangs from inside their cozy armor, glowering back at the inhospitable world they call home.—Shiv Kotecha

The Estate of Joshua Caleb Weibley

Chart | 74 Franklin St

On view through February 15, 2025

In the early 1990s, following the blockbuster release of the Nintendo Game Boy, some especially ardent button mashers started seeing puzzle pieces falling in their peripheral vision, especially when lying in bed, half asleep. Colloquially dubbed “the Tetris effect,” these sensations were eventually given a clinical name by cognitive psychologists. The estate of Joshua Caleb Weibley takes that term for the title of its new show “Game Transfer Phenomena,” a sculptural installation on view at Chart.

The first thing I noticed about the installation is how low it is: seven custom-built pine crates—one for each of Tetris’s canonical tetrominoes—are spread out upon the floor of the gallery's basement level. Some of the crates are open, some are closed; some are empty, some contain their L- or T- or Z-shaped cargo. Trickery abounds: I kept wondering if the closed crates were empty or full. (The tetrominoes—composed of cube-shaped units—are made from SolidSurface, a DuPont product used to make countertops; it looks like a mixture of granite and Laffy Taffy.) Even the creative entity here—“the Estate"—feels like a cheeky riddle, with its suggestion that the artist formerly known as Joshua Caleb Weibley has passed into another realm. Chart’s press release informs us that “active production of artworks by its founder and executor formally ceased in 2024.”

Tetris is a parable of accumulation—players are trying to get rid of all the pieces, not rack them up. Forms disappear; an artist stops making art. The sculptures are accompanied by composer Jordan Dykstra’s hypnotic score, which is made up of—you guessed it—seven tones. Dykstra’s central sound is metronomic, made by striking Weibley’s crates with a hammer—it plays at 60 BPM, about the speed of a heartbeat. The effect is a bit hallucinatory, also palliative, with viewers left dazed, puzzle pieces floating pleasurably at the edges of their vision.—Will Harrison

Ian Miyamura

Bureau | 112 Duane Street

On view through February 15, 2025

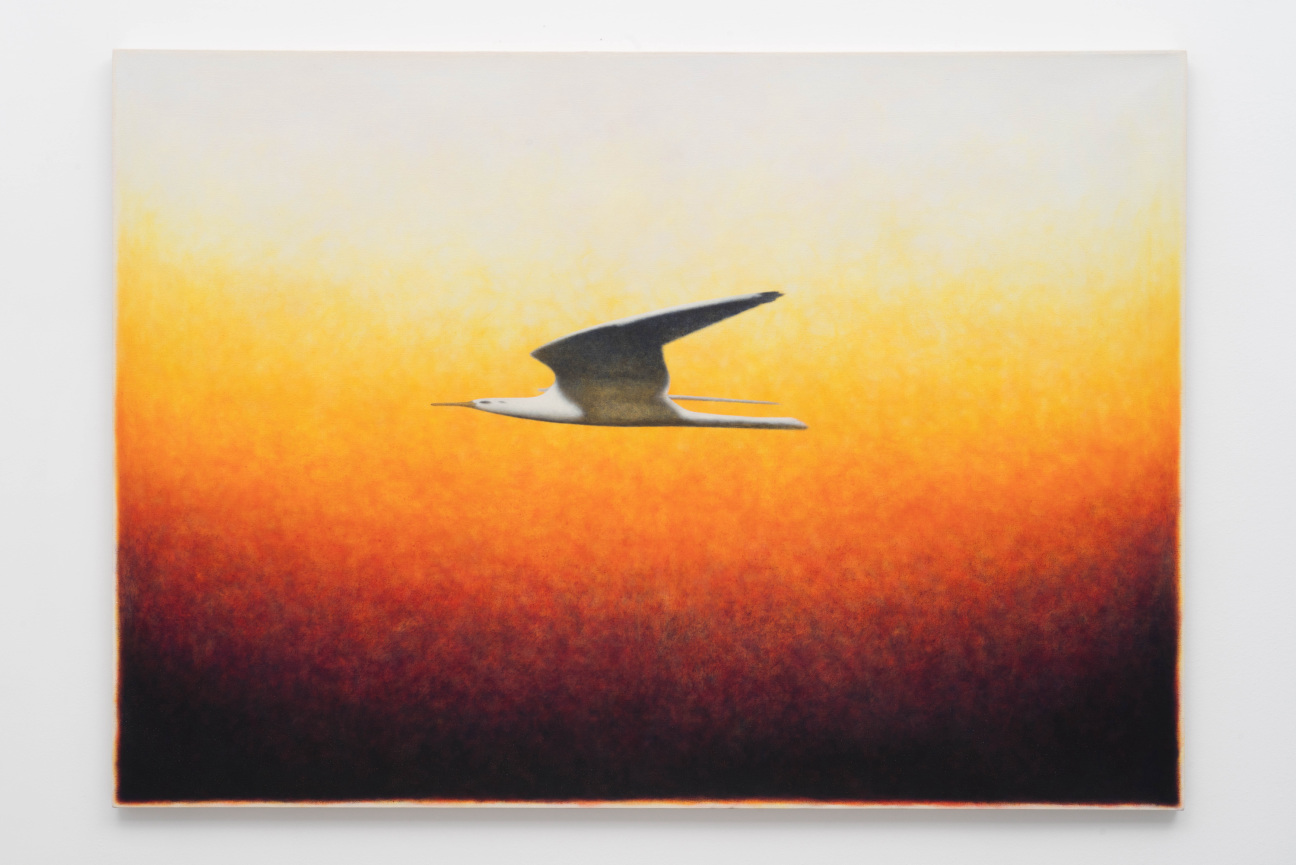

The Latin verse in girum imus nocte et consumimur igni, commonly attributed to the poet Virgil, is a palindrome, which you can see for yourself by reading it in reverse. It translates to something like “we go round and round in the night and are consumed by fire.” Ian Miyamura broke the line in half to title two of the meticulous oil-on-muslin paintings in his debut at Bureau. The show, “They Learned to Look Up and Down,” opened three days after the Los Angeles wildfires began, and the image in girum imus nocte, 2024, felt uncannily apropos. A seagull cruises through a burning, stippled gradient; the dense violet at the canvas’s bottom turns golden as it rises, then pales to pure, eye-searing light. The bird’s sculpted contours resemble those of an industrial object—maybe a warplane.

The second painting, et consumimur igni, 2024, which also shows a seagull, flying in the opposite direction, completes the verse, but is hung on a different wall as if it were unrelated to the first. The off-kilter tone set by such choices is underscored by the clash of styles on view, which include both abstraction and photorealism. Strange, small-scale, grisaille pictures depicting H.R. Giger-like thrones and figurines from the tabletop game Warhammer, are made even stranger by their velvety surfaces and tiered wooden artist’s frames. A group of post-De Stijl paintings might seem to be the natural enemy of Miyamura’s numinous goth statements, but the strength of the artist’s craft unites them in a common cause. This series of two-panel, compositions—each dubbed fraternal painting—adds depth to the artist’s bewilderingly harmonious multitrack presentation. (One of the works is installed with its two parts at a right angle, in a corner of the gallery, adding a moment of mirth to the show). And for the exhibition’s pièce de résistance, the artist hand-copied his self-authored press release, framed it, and laid it on the front desk—a gesture exemplary of a practice as mysterious as it is recursive.—Paige K. Bradley

in your life?

in your life?