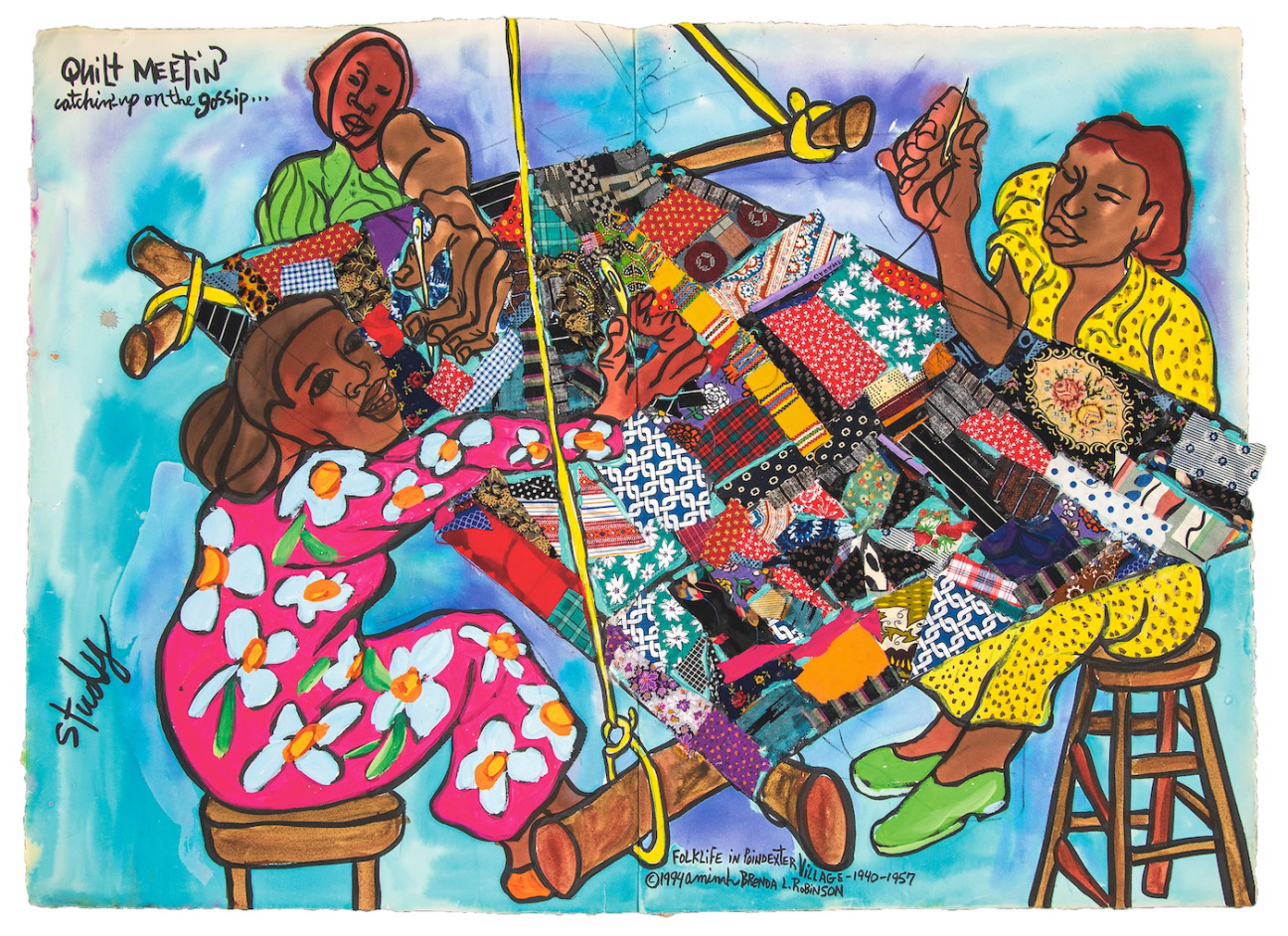

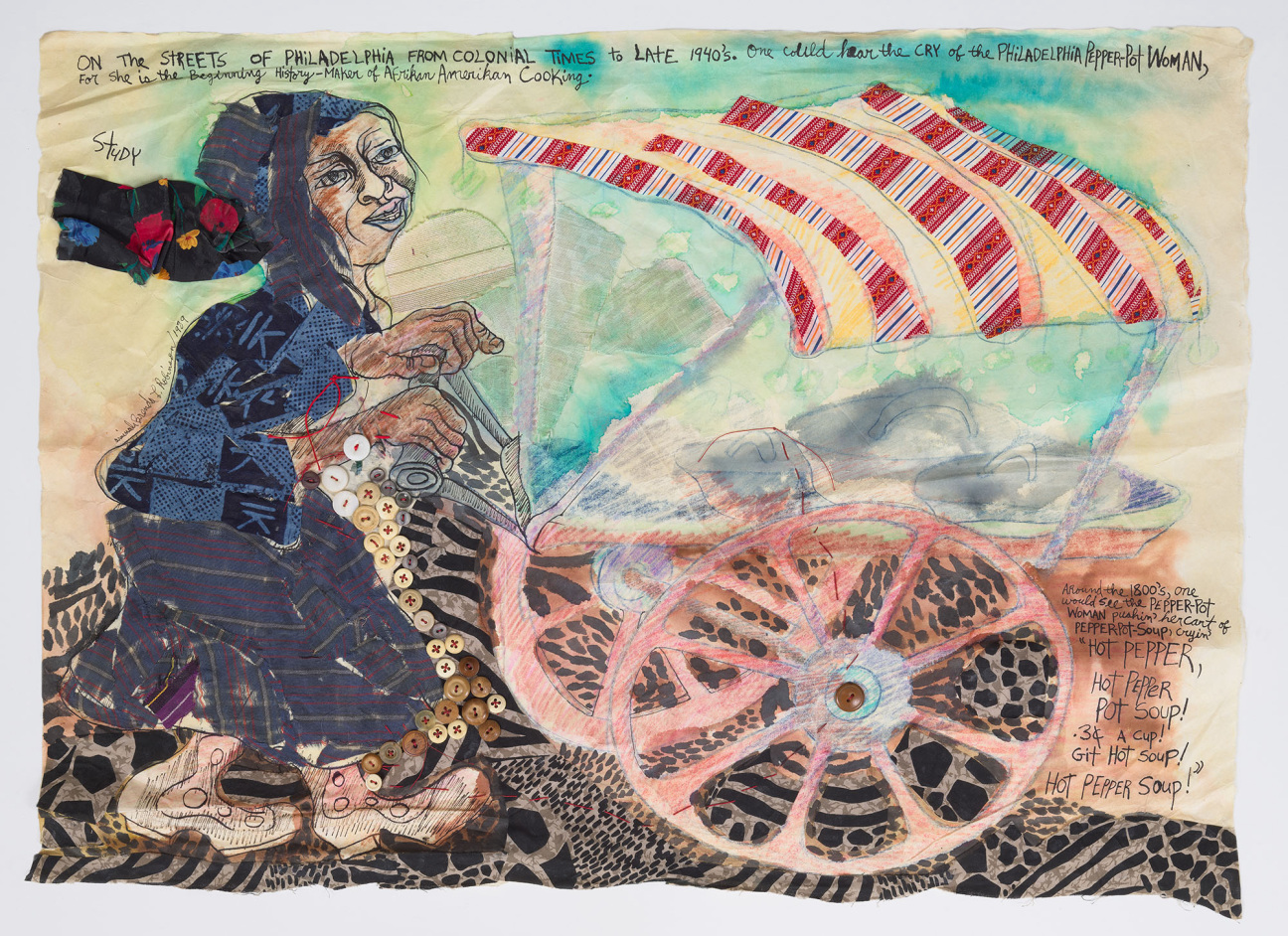

The spirit of Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson—an artist consumed by making, whose life never stopped feeding into her practice—tends to lurk in any room where her work is on view. Perhaps that’s due to her genre-bending, all-over approach, her presence still emanating from the assortment of found objects she incorporated into drawings, sculptures, and her signature, years-in-the-making rag paintings.

For one sculpture in “Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson: Character Studies,” a show of Robinson’s work at Fort Gansevoort in New York (on view through Feb. 8), the artist placed a patterned skirt, shirt, and hat fashioned out of bright orange feathers onto a stick-like figure she constructed using raw wood and hogmawg—a mixture of materials like animal grease and mud that her father had used to make books. Handed-down materials, methods, and memories anchor Robinson’s practice. The artist, who won a MacArthur Foundation "genius” grant in 2004, was a storyteller. “She is either revisiting important moments in history or documenting history as it was happening,” says Maggie Dougherty, a director at Fort Gansevoort.

The show, which inaugurates the gallery’s representation of the artist’s estate, is part of a growing effort to promote the work of Robinson, who died in 2015 at 75. Having grown up in Columbus, Ohio, she cultivated a close relationship with the Columbus Museum of Art and bequeathed her art, writings, and home studio to the institution. Beginning this year, an exhibition of her work organized by the museum will travel to the Springfield Museum of Art in Ohio, the Newark Museum of Art in New Jersey, and the Mobile Museum of Art in Alabama.

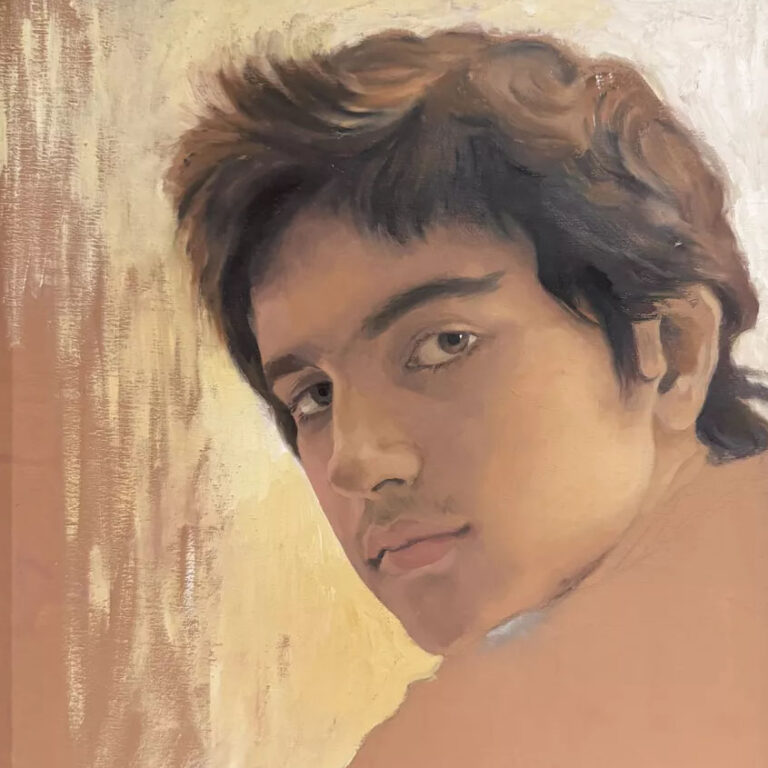

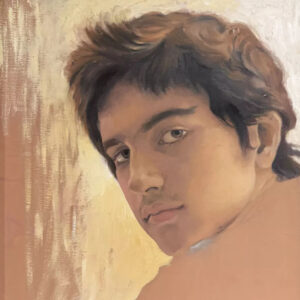

Robinson’s multidisciplinary oeuvre—which begins with a self-portrait she made in 1948 at 8 years old and even includes journals she’d kept throughout her life and catalogued in her art-filled home—forms a nonlinear map of Black life. She combines depictions of her everyday experiences with stories her family shared about their lives. Unwritten stories. Traumatic stories. “A visual record of our existence,” Robinson once said.

One sculpture in the Fort Gansevoort show, called Shaman, honors her great-aunt Cornelia Johnson, who Robinson considered a conduit for their family’s ancestral ties to Africa. Before moving in with Robinson at Poindexter Village in Columbus, Johnson had been enslaved in Sapelo Island, Georgia. Many of the artist’s pieces, especially her drawings featuring vibrant, cartoon-like subjects, memorialize the ongoing customs and traditions of places like these. Robinson would research these ancestries to unlock stories of generations of Black people extending well beyond it.

As much as Robinson’s compositions are unmistakably distinct, revealing an artist with a masterful hand, the repeated appearance within her works of other hands—beautifully articulated, expressive hands—suggests that she identified less as an author and more as a messenger. As professor Lisa Gail Collins put it in the artist’s catalogue, Robinson draws us close “to pass on what was handed down to her.”

In light of this, the Columbus Museum plans to use the proceeds from the gallery show to fund the Aminah Robinson Legacy Project, an initiative focused on promoting not only Robinson’s work, but other African American artists and writers as well, according to Brooke Minto, the museum’s director. Expanding a residency program, which began in 2020, will enable the artist’s legacy “to continue to grow,” she says.

in your life?

in your life?