Getting inside Char Jeré’s Bushwick apartment requires some careful maneuvering: turning sideways to squeeze past paintings stacked against the walls, stepping over painted plywood sheets on the floor. Clunky electronic contraptions from the 1990s are strewn everywhere, as are 2x4s and paint cans. Pointing to the warped edges of a plywood panel I'm standing on, Jeré says, “I'm trying to get this to flatten out, so I thought walking on it would help.”

The commingling of domestic space and immersive art is a salient feature of the artist's exhibitions, too. For her solo show at Artists Space in New York last year, she turned a gallery into a living room-like installation, complete with an antique cabinet, desk, and tables. Some of her sculptures resemble piled-up household clutter. It’s still more orderly, however, than her own home, which she once likened to a laboratory. “Building a home,” she said, “especially for Black women, means constantly subverting and transforming what an object or space is designed to do. For me, that can mean turning boxes into chairs and tables, and getting electronics to do things they weren’t made to do.”

After the New York dealer Andrew Kreps visited the Artists Space show, “something about it stayed with me,” he says. “It was a complete environment—there was just so much going on in there.” Shortly thereafter, he met Jeré by chance at his gallery. When he realized that it was her show he’d just seen, he immediately asked her for a walkthrough. “The work all made sense to me at that moment,” Kreps remembers. Now, he's staging Jeré’s first solo show at the gallery, “Remembering the Mind: A Study in Progress,” which opens Jan. 10.

Jeré, who is 41, was born in Rochester, New York, where her great-grandmother fled from Mississippi. “It’s important to say ‘fled’ to Rochester—almost to Canada,” she says. Jeré had been making art her whole life, but when she went to college, her mother urged her to pursue a more practical path. She initially attended SUNY New Paltz to study public relations but quit before graduating. She decided to finish her education only after reading the Black Liberation Army activist Assata Shakur’s memoir. “I was like, 'You can’t be dumb,'” she says.

A key aspect of the Andrew Kreps show is an exploration of the concept of “black noise.” Jeré, who returned to school to study data visualization and sonification at Pratt before getting her MFA in sound art at Columbia University, explained that many of the vintage-looking devices on the floor and countertops in her apartment were white noise machines. “White noise is supposed to be the whole spectrum,” she explains. It’s considered a soothing, atmospheric sound, which some experts think mimics the inside of a womb. But others say it’s too omnipresent in our lives, and the auditory system needs a break.

To Jeré, white noise stands in metaphorically for the ambient swirl of mass media and cultural expectations, from beauty standards to stereotypes. In other words, “things that Black folks or disenfranchised folks have to filter out,” like the “relentless hum of systemic racism.” By contrast, “black noise” is “nothingness” in its traditional conception, Jeré continues. “It’s silence, which I think is really interesting. We've been silenced, right? And erasure has happened.”

Jeré’s work aims to challenge the idea that silence equals passivity. She's exploring the potential of black noise as "both noise and signal," but to her it is more of "an exercise in listening or trusting one's intuition." At the Andrew Kreps show, several white noise machines will be playing, alongside at least a dozen sculptures of black clay ears, dilated to about three times larger than life, on the walls. It’s her take on Frantz Fanon’s 1952 book Black Skin, White Masks; in this case, “it’s black ear, white noise.”

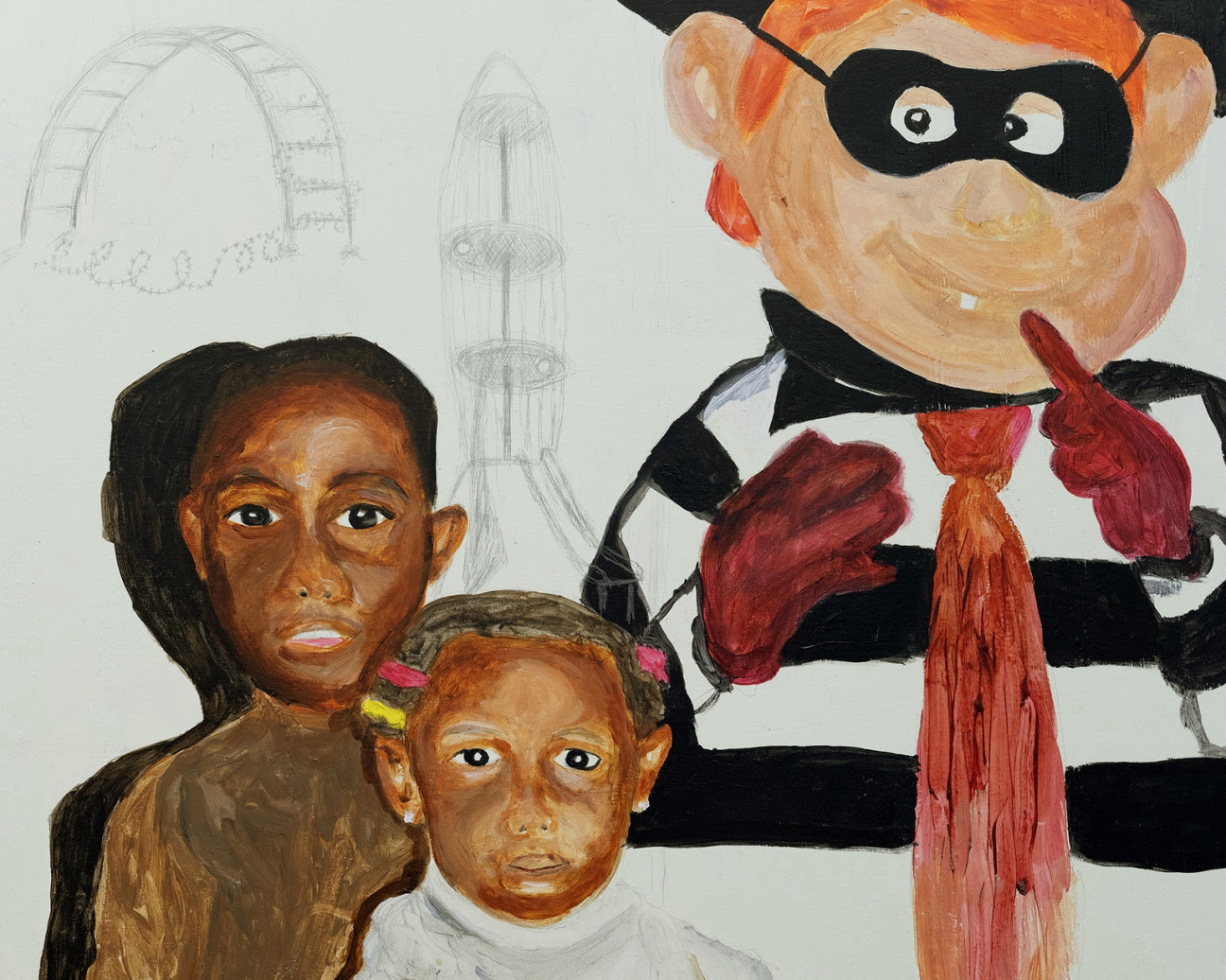

There will also be a performance involving gospel singers and several paintings on view. The canvases, mostly done on plywood, depict characters from Jeré’s life, including her great-grandmother, Raggedy Ann, and the McDonald’s villain the Hamburglar, who is a recurring figure in Jeré’s chronic night terrors. “They're circling around,” Jeré says of the imagery.

This fragmentation, where “everything is just kind of spiraling,” stems from her identification as an “Afro-Fractalist” artist. If Afro-Futurism involves imagining a speculative future through a Black lens, “Afro-Fractalism” is about rejecting the idea of linear time entirely. Jeré described the concept in an interview with Bomb as “a way of defiling a linear, colonial, capitalist temporality. It makes the future less of a destination and more of an ongoing rehearsal or ritual. The future and the past are happening constantly and simultaneously. For me, Black futures take the shape of a fractal.”

Jeré’s live-work space embodies this sensibility. As I begin to leave through the kitchen, she points out several more things she’s working on: a torso-sized sculpture of a white ear, satellite radios she found on the street, and an old TV. Maybe they’ll be part of the Andrew Kreps show. Or maybe they’ll appear in one of her upcoming exhibitions. In March, Jeré will show a short documentary as part of a group show at the Center for Curatorial Studies's Hessel Museum of Art at Bard College, and later in the year, she'll present a project at Paris’s Palais de Tokyo. She works in all media simultaneously, threading together personal and cultural histories, consciousness, and dreamstates. “I have no boundaries,” Jeré says.

in your life?

in your life?