This past year, CULTURED spoke to dozens of artists who offered intimate glimpses into their creative processes, personal journeys, and the philosophies that shaped their thinking. From Salome Asega's belief in the classroom as a sanctuary of experimentation to Joan Snyder's revelation of painting as her first true language, here are 12 of the most illuminating excerpts about the connections between personal experience and artistic expression from 2024.

Salome Asega, profiled by Karen Wong

“The classroom is an active place to work through complex, layered challenges without restraint or external pressure,” says Asega. “There’s some level of safety to try things out, fail, try again, and come back. Output isn’t as important as process to me because it’s in developing a process that we can refine and iterate on asking better questions.”

Agnes Denes, profiled by Jacoba Urist

“My work is to communicate with people and a betterment of people, especially today in a world of confusion,” Denes says, pointing to a famous Life magazine photo of her in a wheat field on her computer. “Every era feels confusion and upheaval because you live it. But I think this is different. This is more meaningful, so any intervention, any betterment, is important.”

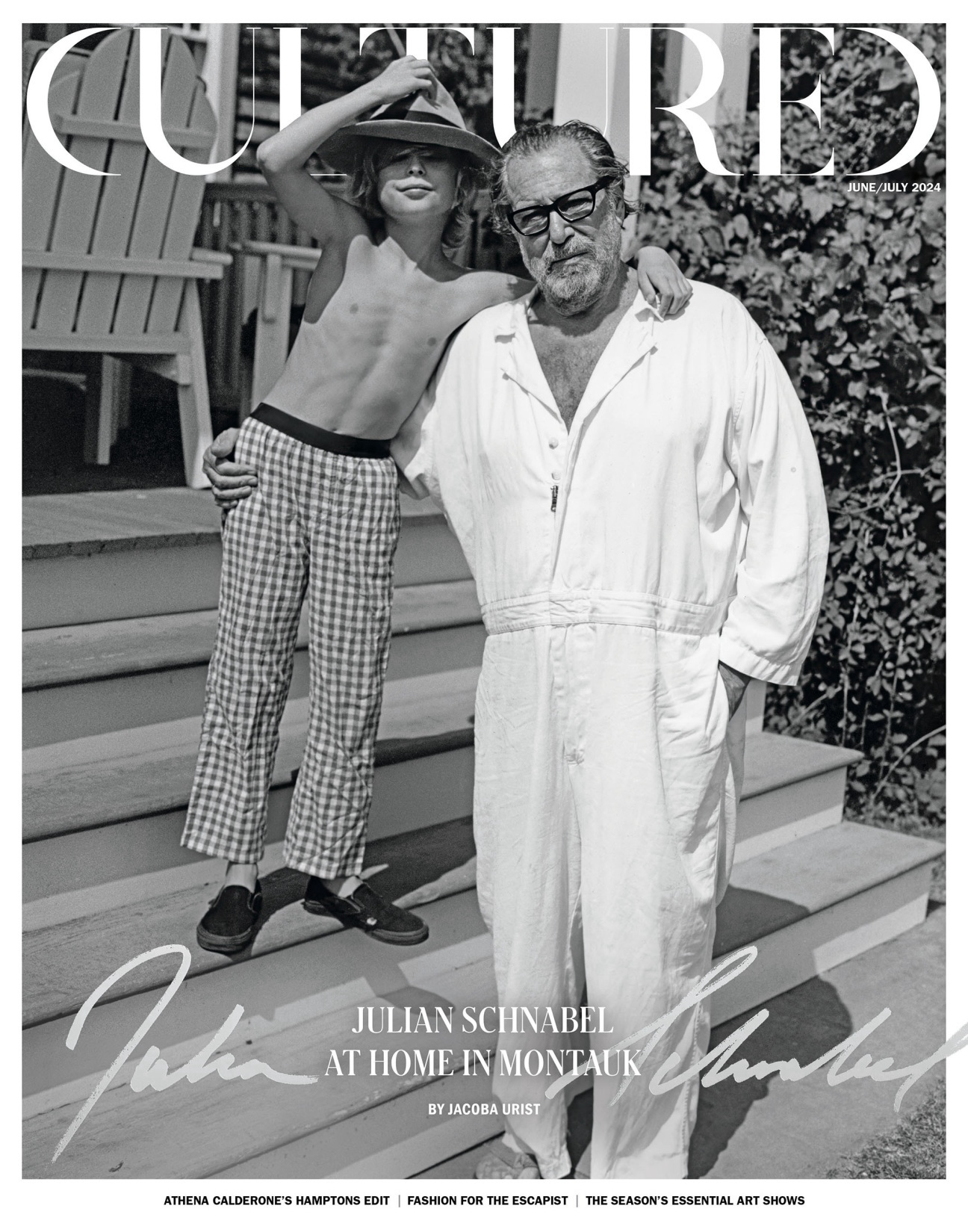

Julian Schnabel, profiled by Jacoba Urist

“Everything that’s not in the painting doesn’t exist,” Schnabel says. “You and I are transient. On the other side of this…”—he points to the confines of an artwork—“no-man’s-land. But inside these things, when I was alive—I was responsible for that. When you make something, it’s about leaving it there so someone could commune with it or feel like you’re communing with them through that thing.”

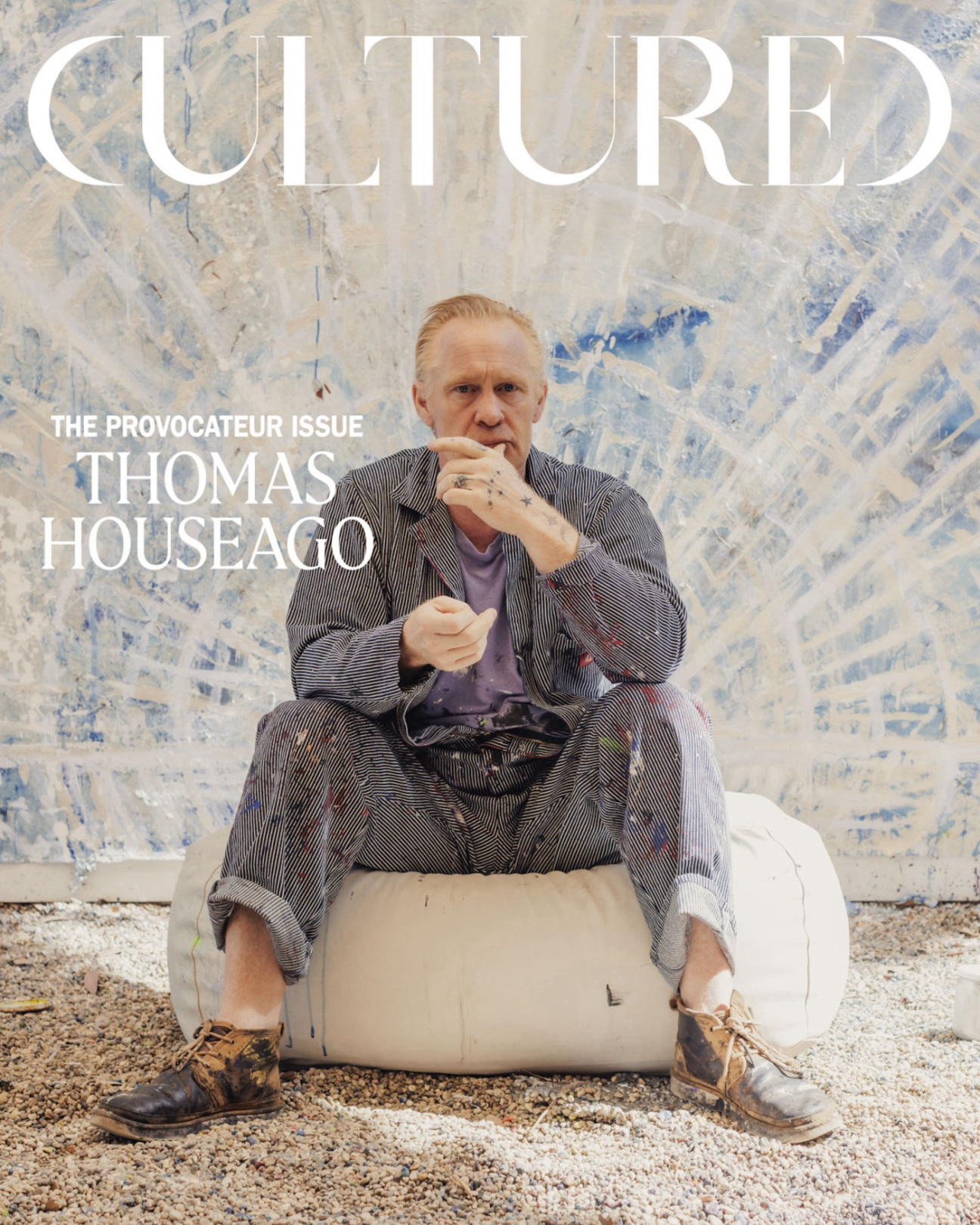

Thomas Houseago, profiled by Ella Martin-Gachot

In Houseago's Lévy Gorvy Dayan exhibition, the path to recovery is punctuated by a turn toward the celestial on the fifth and last floor, with a skylit mural depicting the phases of the sun and moon. “No matter how triggered or fucked up I am, I always find the dawn beautiful,” Houseago concludes. “The whole show in a nutshell is: There’s hope. How do you become an ambassador of hope?”

Maja Ruznic, profiled by John Vincler

“I’ve often thought the imaginative space that feels so comfortable to me, came to me from trauma,” the artist says. At age nine, in an Austrian refugee camp, she remembers being given a set of watercolors, as well as a red lamp that a doctor told her would treat depression. Painting, and the use of color, became a way of both exploring and representing her emotions. “I feel like I really lucked out in that … to deal with the trauma, I became obsessed with creating worlds.”

Joan Snyder, profiled by Ella Martin-Gachot

Before her Whitney Biennial inclusions, before her Guggenheim Fellowship, before selling out solo shows, Joan Snyder was an anxious sociology student at Douglass College. Then she discovered painting. “It was literally like speaking for the first time,” she recalls. “I could say what I wanted to say.”

Loretta Dunkelman, profiled by Brian Boucher

What Loretta Dunkelman knows beyond any doubt, however, is the satisfaction she takes from the outside world's enjoyment of the piece. “Even people who know nothing about art like that painting—my cleaning lady, or the guy who came through to do some electrical work recently,” she concludes. “There’s something very pleasurable about making something everyone can engage with.”

Charles Atlas, profiled by Helen Stoilas

Despite already having done the hard work of a retrospective himself, pouring over his back catalog with a critical eye and selecting the pieces he wants to redisplay, actually seeing all that work in a single show is a different experience altogether for Atlas. “I realized that I never showed more than one piece at a time. Seeing all these pieces together, it kind of just hit me, you know, that this is… it's big, it encompasses a lot of ideas,” he says, adding later in the conversation: “It's a little overwhelming to see everything from 50 years gone by.”

Yvonne Wells, profiled by Ella Martin-Gachot

Have these, and the many accolades Yvonne Wells has accumulated throughout the years, changed how she feels about the word artist? “Whatever they call me is what I am,” she concludes. “It doesn’t matter if I’m folk or fine. I just continue to do what I do. My head sees, my heart feels, and my hands create.”

Evan Holloway, profiled by Jori Finkel

“It’s too early for words / To use language to fix on a meaning / Like when you open your eyes / and you don’t apprehend it’s the ceiling,” he sang. “You can feel with your body / You can sense with your mass / Understand three dimensions / Teach your own master class,” he intoned in another, which just might be the only song ever to cite William James’s theory of “The Spatial Quale.” (Holloway described it as “the quality of sensing an object with your body” and “a set of ideas that have been a really big influence for me.”)

Margaret Lee, profiled by Julia Halperin

Reading psychoanalysts like Sigmund Freud, Mária Török, and Nicolas Abraham—as well as The Artist’s Way—gave Margaret Lee permission to loosen her grip in both life and art. In her own therapy, she worked to cultivate a truer, almost pre-verbal version of herself. “Becoming inarticulate is an extremely scary thing,” Lee says. “It’s the most vulnerable I’ve ever been.”

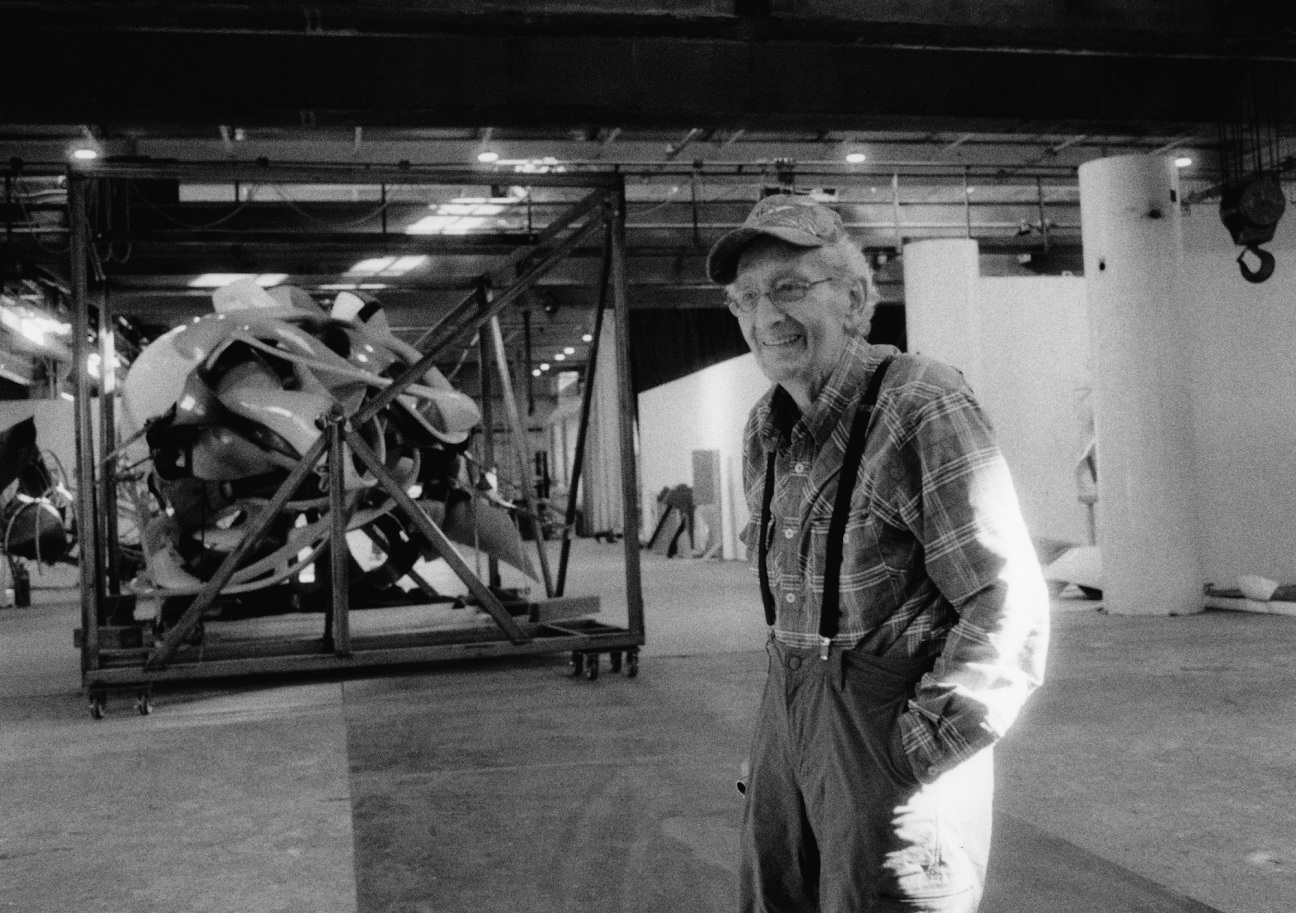

Frank Stella, profiled by Chloe Wyma

As for what is inspiring him now, Stella says he’s “remembering art more than looking at it” these days. He still “get[s] hung up a lot on [Vassily] Kandinsky,” particularly the painter’s once disparaged late work, with its decorative profusion of embryonic, ameboid, and otherwise organic forms.

in your life?

in your life?