Zeinab Saleh gives more reverence to the textures of her daily life—prayer mats, kitchen cabinets, crumpled sheets—than most painters do to the human body.

The rising artist, who was born in Nairobi, grew up in London, and recently moved to Dubai, remembers the exact moment her domestic muses came to her. As an art student, she was taken with the practice of life drawing. “I would draw to scale, using a pencil and different methods for proportion drawings. I really enjoyed the process of looking, making a mark, and checking it,” she recalls over Zoom. “I loved how, when using a pencil this way, it could be incredibly accurate. It’s not just about relying on what you see.”

But live model sessions were expensive, so Saleh turned to her mother’s living room. “I was like, ‘Well, I have this big sofa, these rugs, and objects. The sofa kind of feels a bit fleshy with the folds it creates with the pillows, so I’ll just use this.’”

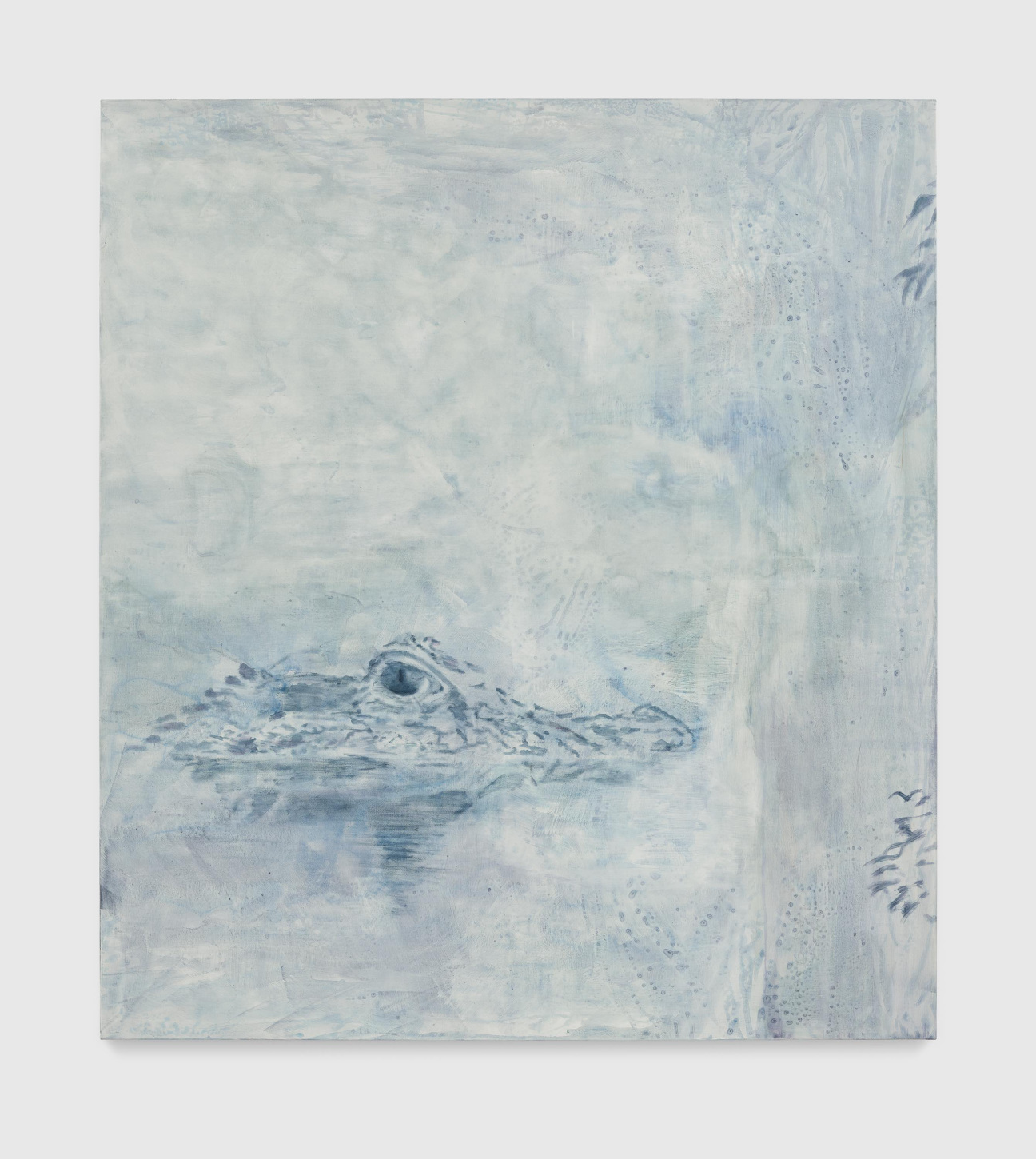

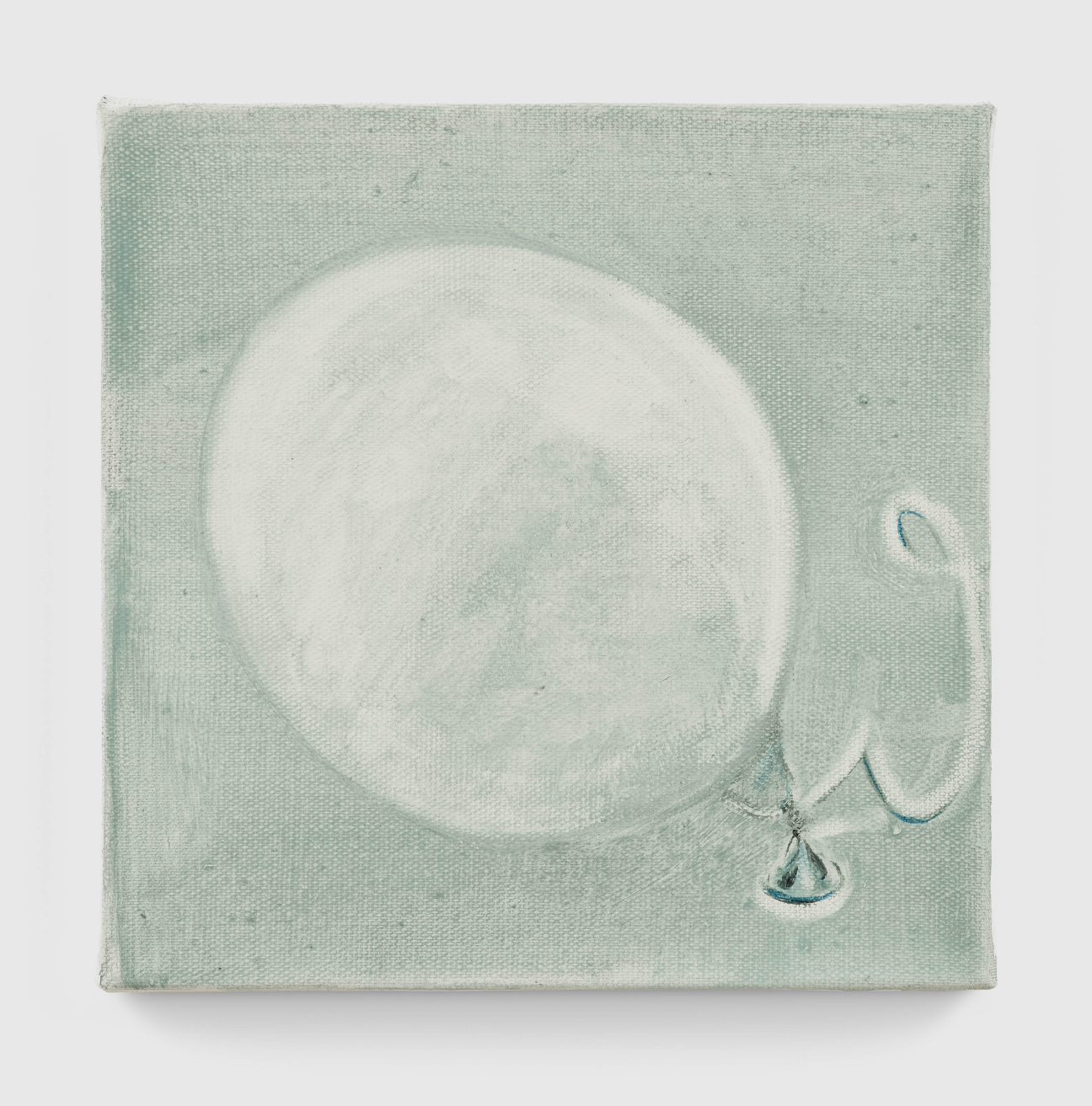

The resulting canvases are both time capsules and emotional palimpsests, retaining and refracting the attachment, both affective and aesthetic, the artist displays for objects. Like Bonnard and Cassatt, Saleh doesn’t just dispatch from the domestic, she revels in its capacity to reveal as much about its beholder as its keeper. This winter, she has brought her muted palette and tonal topographies back to London for her first solo show with David Zwirner, “The space {between},” on view in the gallery’s Upper Room through Jan. 11. At 28, Saleh already has solos at the Tate Britain, Camden Art Centre, Champ Lacombe, and Château Shatto under her belt. The latest previews what the next chapter of her practice might look like, as half of the works on view were made following her move to Dubai, whose climate and iconography are subtly shifting her eye.

To mark the occasion, Saleh sat down with CULTURED to discuss her first encounter with contemporary art, what she looks for in a curator, and why giving a painting room to breathe is vital.

CULTURED: How long have you lived and worked in Dubai? When did you make the move from London?

Zeinab Saleh: I can't believe it's been eight months already. The time has just flown so quickly.

CULTURED: How has working out of your new home studio in Dubai affected your work? Given your focus on interior worlds, has the change in landscape or geography changed anything?

Saleh: In London, I had my studio at Gasworks, with amazing artists who are residents there. I would have really nice conversations with people like Michelle Williams Gamaker, a video artist, or Nicholas Byrne, a painter. Those were super helpful for the development of my work. It's been a bit tough to be honest to be in my studio at home now. So I guess my way of making has changed slightly because I'm more reliant on my own decisions without a soundboard—having to just really live that solo-artist-in-the-studio kind of trope.

Then there's the change in temperature. It's really hot here, so when I do my initial watery layers of acrylic washes, they dry a lot faster than they would when I was in London. Without the AC, the room can get up to 27 degrees Celsius. Here it takes three hours for acrylic wash to dry, whereas in London I would wait for the next day, come back, and be surprised.

CULTURED: Has the shift influenced the themes in your work, or have they carried over from your time at Gasworks to Dubai?

Saleh: The UAE has so much empty space. You'll see lots of empty areas of land, and the homes, galleries, or institutions feel really large. So maybe my paintings feel less claustrophobic. With the acrylic washes I do as the first layer of my works, I often put crumpled pieces of cloth or fabrics [on the surface]. Sometimes I'll put in organic material, like plants or leaves. I've been picking things from my surroundings, so the type of leaf or flower I get is slightly different. So there’s the local ecology slowly seeping into the work. And maybe some of the motifs are slightly more arabesque.

CULTURED: Tell me about your first interactions with art. You went to Slade, but I read that you had initially considered studying psychology.

Saleh: With the British schooling system and the way GCSEs are structured, art education was very focused on the Western canon when I was a student—I know things have improved now. It wasn’t until I switched from physics to art for A-levels, around 16, that I was exposed to contemporary art. I started visiting galleries and encountering work that was unlike anything I’d seen before—art I didn’t even realize could exist. One of the first works that deeply affected me was artist Maha Malluh’s “Food for Thought” series, using Arabic Quran citation cassette tapes. I recognized those tapes from my mom’s old drawers, and seeing them installed in such a unique way was incredible. Coming from an Islamic background, it was exciting to see how these objects could be repurposed and how anything could be art. The tapes felt like a stand-in for the artist’s identity; I could tell where they might be from or how their upbringing was. That was far more engaging than what I’d been taught in earlier stages of art education.

CULTURED: Can you speak to how the domestic objects you depict are afforded new meaning on the canvas versus when you’re simply looking at them, sitting on them, or seeing them in real life?

Saleh: I really enjoy the ambiguity in painting and drawing. When objects reach the canvas, they become distorted, more fluid, and morph into other shapes. What’s interesting about painting as a medium is that you’re never really sure exactly what you’re looking at. This isn’t always present in film, writing, or other visual media, like advertising, which often tells you what to think. With painting, the way you interpret it often says more about you than what’s actually on the canvas. For me, when something moves from calculated, accurate drawing into something more fluid, that’s when it becomes exciting.

CULTURED: How did your palette find you? I’m interested in the haziness of your colors—the blues, whites, grays, and occasional peach—and how they create an atmosphere that seems to seep off the canvas.

Saleh: I worked a lot with charcoal and charcoal powder for a few years, so my palette naturally became quite gray, aside from the initial acrylic underneath. I had a solo show with my gallery, Château Shatto in LA, and someone mentioned the paintings felt very London. I thought, Is it because of the mistiness, the London fog, that kind of blur and haziness? Between 2022 and 2023, I traveled to places like Seoul, Marrakesh, Biarritz, and Kuala Lumpur, and those experiences probably influenced my palette. They made me feel excited about different tones, especially the Marrakesh blue. I was obsessed with how vivid and incredible the blue was in painted buildings and ornaments. Now that I’m working more with acrylic, I can create any tones I want. It’s less limiting than charcoal.

CULTURED: What is your relationship to nostalgia? Is that a word you feel is appropriate to describe your work, and how do you relate to it as an artist?

Saleh: I totally see that there is a sense of nostalgia [in the work], and that's because of the haziness and the depictions of home, which can feel very comforting or familiar. The entire body of work I did for the Tate Art Now presentation was painted from my everyday surroundings in London. In one of the paintings, it’s the view from my kitchen, with the sink and a cupboard. There’s a rug on the floor, the bedsheets, prayer mats—all spaces from my flat, which I no longer live in.

CULTURED: Nostalgia evokes a certain liminality for me. It’s not the present, and it’s not what actually happened—it’s this strange in-between state. That seems to relate to the title of this Zwirner show, “The space {between}.”

Saleh: I guess with the title I wanted it to feel quite open to interpretation—like the space between now and then. I feel like the time we’re living in right now, compared to when Rihanna dropped her song “Work,” is a completely different world.

CULTURED: How do you live in the world today differently than when you lived in the summer of “Work” dropping?

Saleh: That summer when “Work” dropped was such a beautiful time. The world felt like such a great place. But the exhibition title is not necessarily about an exact moment, but the space between “now” and “then”—the space between the works and the objects in the paintings. I often leave negative space, which for me is room for the viewer to connect the dots or just have breathing space.

CULTURED: In your more recent work, are there any departures from past practices you’re noticing?

Saleh: I worked on a lithograph for the Zwirner show, which I’ve never done before. I love printmaking. I’ve done soft ground printing, screen printing, and monoprinting in the past, but had never worked with lithography. I collaborated with a printmaker in New York, and it was an exciting process. It’s challenging, but when they asked if I wanted to do an edition or a print, I immediately thought of The sovereignty of quiet, the painting I showed at the Tate. During that show, so many people asked if I had a print or postcard of it, and I felt bad saying there wasn’t one. I knew right away I wanted to make a print of it, so I decided to create a lithograph from a detail of the painting for the new show. My new lithograph is called Quiet Sovereignty in reference to the painting, which is in reference to Kevin Quashie’s book The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture.

CULTURED: You’ve had quite an ascent over the past five years since graduating from Slade. How has it felt to receive this kind of institutional recognition and reach this point in your career?

Saleh: One of my favorite things about doing these shows is the people I get to meet. I’ve had such positive experiences with the curators I worked with at Tate, Camden Art Centre. Working with Lucy Chadwick from Champ Lacombe and my gallerist Olivia Barrett has been wonderful. I’ve been extremely lucky. At the same time, I’m very selective about what and who I say yes to, which might come down to trusting my gut.

CULTURED: How have you honed that gut feeling?

Saleh: I can’t say yes to many shows because I work quite slowly. I already have a few solo shows I’m working towards, so I’m prioritizing those. I’ve also said yes to things I’m really happy and pleased to commit to, and I always want to honor those commitments first. When deciding, I look for how comfortable I feel speaking with the curator. How are they in the studio? Are they asking lots of questions about the work? Are they curious about the process, the physicality, and the making? An easy red flag is someone vaping on a Zoom—that’s just so unprofessional. So sometimes a red flag is that obvious. Other times, it’s just about going with your gut.

CULTURED: I like the vaping on the Zoom—that’s a fun one.

Saleh: No shade to the vapers. It’s an epidemic. [Laughs]

in your life?

in your life?