Since his days as a rising artist in the 1960s, Carl Cheng has understood that nature is the only thing that outlives us all. In his work, he simulates natural cycles of growth and decay, as well as the human or technological interference therein with pieces spanning sculpture, photography, and installation.

Museum curator Alex Klein first discovered his work while working at LACMA in the early aughts, where she learned about his contributions to a 1970 exhibition at MoMA, “Photography Into Sculpture.” Then, in 2016 she encountered his "Erosion Machines" at Philip Martin Gallery: microwave-sized mechanisms that eerily replicate the natural process of water erosion. This started Klein’s fascination with Cheng and her desire to learn more. “They blew me away,” recalls Klein, who joined the Contemporary Austin two years ago as head curator and director of curatorial affairs. She has been working even longer than that on putting together a survey of the artist’s work, whose studio was incorporated under the name John Doe Company in the late 1960s.

Ahead of the opening of “Nature Never Loses”—which runs through Dec. 8 before hitting the road to stops at the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania, Bonnefanten, Museum Tinguely, and Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles—Cheng and Klein sat down for a conversation on the artistic process, the role of technology in creative practices, and the things that continue to inspire the 82-year-old artist seven decades into his career.

Alex Klein: One of the things that has been so exciting in learning more about your work is how it really set the stage for younger artists who are thinking about natural processes and the environment, identity, and technology—and some of the questions they’re asking about the art market and art system. What has it been like looking back over six decades of work? Have you found new resonances?

Carl Cheng: Since I just finished visits to the Museum Tinguely [where "Nature Never Loses" will be shown], it brought together a lot of things I was wondering about myself in terms of art and technology. Fusing art and technology is not a permanent thing, even though it seems like it. They’re planning the 100th anniversary of [Jean] Tinguely’s work. A lot of his pieces didn’t work, so they just sit on the wall. But the exciting thing is that there is somebody who tries to make it work, because it’s very difficult.

My work is a little more developed. It can last a little longer but not forever either. It was driven home for me that this is what art and technology really is. You can’t maintain something like that forever. You have to put it in context. I also know that there’s a finite amount of content that my work fits into. It will be superseded in the future, too. So it kind of comes around for me. What happened back then seemed revolutionary, but I’ve survived it all and continued doing what I do. There’s no one thing that works forever.

Klein: There’s been a lot of talk about your work being very prescient and ahead of the curve. And your response has often been, “No, I was just processing the world around me and I was, in some sense, a documentarian.” That's a really interesting remark because it also highlights that some of the issues in your work with the environment or maybe changes in technology look slightly different on the surface now. But those were urgent, pressing concerns then, too.

The smog in Los Angeles would have been really thick because there weren't emission controls. You were growing up in the valley and seeing orchards turning into tract homes, much like we're seeing in Austin with the tech industry developing the landscape. Or thinking about new technologies and computing systems coming into the fold, here we are talking about A.I., et cetera, usurping daily life.

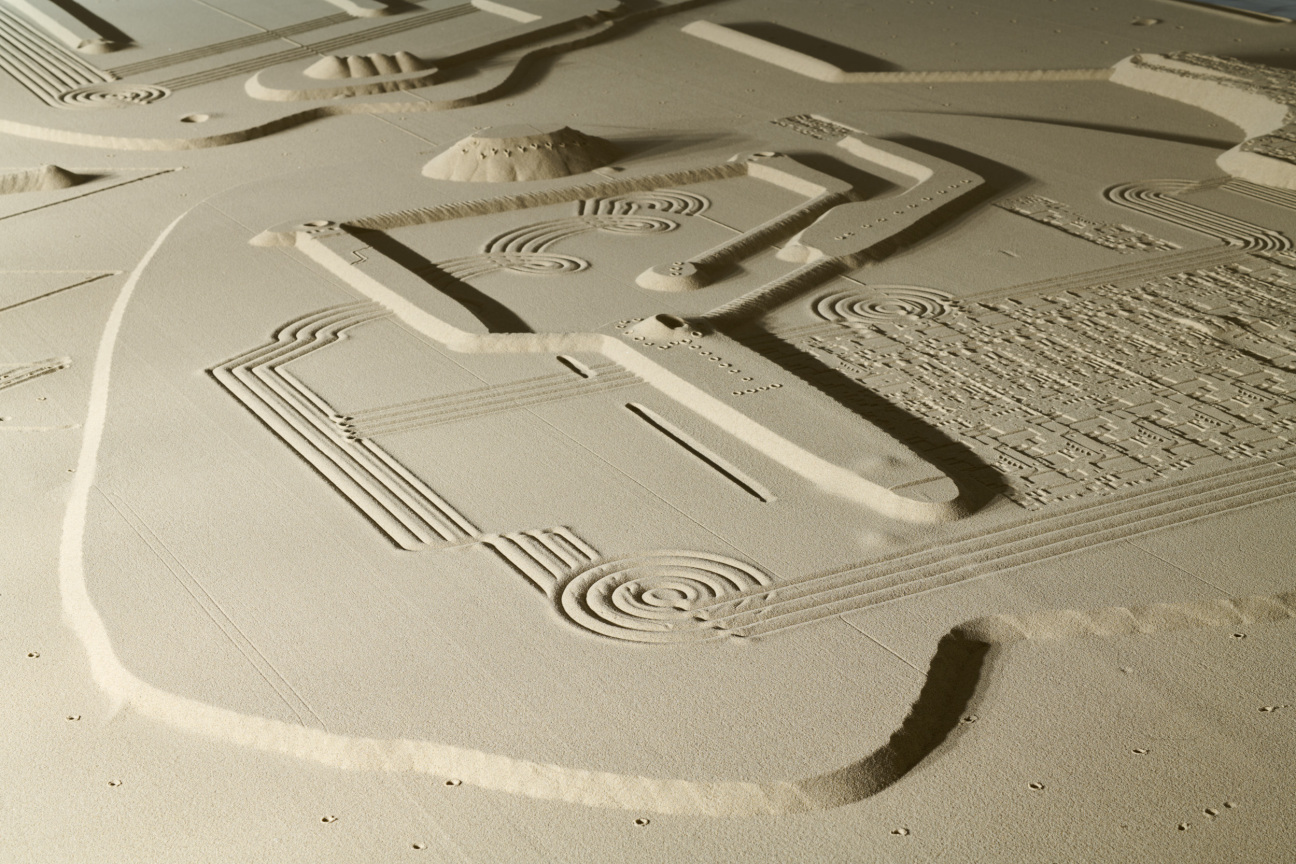

One of the other things that comes up a lot is that, with the way that you work with the technology, there's often an assumption from viewers that you're working with a more contemporary technology like 3D printing. When people see the sand rake, for example, I sometimes get asked, “Is that 3D-printed?” I tell people, “No, this is 8 to 10 days of solid work sitting there, slowly dropping sand, blowing air, dropping water.” It blows their minds and it gives them a completely new appreciation for it because they're mapping contemporary technology onto your processes.

Cheng: There's much more of a performance aspect when you're doing it like I do because the tool itself is kind of worthless. It just does what you tell it to do. Even a lot of times it doesn't do it. To me, it's more important to bring out the human aspects of what we are rather than what a tool can do for us.

Klein: I would argue, Carl, that it raises really profound questions about the tools and technologies that we do have in front of us like A.I. or 3D printing and what role a human needs to play in it for it to create. If you map that thinking onto another kind of technology, you could argue that the human direction is necessary because we're in this moment of debating the role of technology in society.

To advocate for the necessity of the human in all of this is really important because otherwise it takes us down a really scary path. Your work also helps us to think about how these things really are just tools at the end of the day. But the question of impermanence is also a consistent theme in your work, whether it's your erosion experiments or the sand drawing at the conclusion of the exhibition. We have this incredible work that's installed in the exhibition that will just get wiped away at the end. All that you'll be left with is the tool.

If you want to follow it to its fullest you could think of it as a metaphor, not just about the impermanence of an artwork and its impossibility to enter into capitalist consumption, but as a metaphor for how fragile and precarious the human landscape ultimately is in the face of nature and climate change.

Cheng: I agree with you totally.

Klein: I'm super excited for a younger generation of artists and scholars and audiences to be introduced to your work and find inspiration in your practice. And also to learn from some of the bigger issues that your work teases out. There is a specificity to each of the venues that is going to be really interesting. From Austin, with the tech industry here and the environmental issues with the pressing concerns of climate change, we're sitting in the state that drives the oil industry and has the hottest summers on record. In Philadelphia where the Duchamp collection is—that's such a huge influence for you, and has one of the oldest Chinatown communities. Bonnefanten has this humanistic theme to their museum collection. Then the Tinguely Museum in Basel has that direct connection to his kinetic sculptures. And finally landing in Los Angeles, your hometown. We're thinking about also making a new work for that one, potentially a water work. What is this opening up for you in your practice and your studio and your inspiration?

Cheng: Whatever it is, it's influenced by what I see around me. One of the things I was thinking about is the benefit of doing something with grass. What if I do things with nature? That's something that those [European] cultures still sometimes don't think of in terms of how the modern person does. In the past, they have not thought of human beings as part of nature and that's a real basic fundamental difference. It's easy for us in the States to say that human beings are part of nature. But there are people in these countries whose religions don't allow it. They have different ideas of what mankind is. I'm not saying that I necessarily believe in what they believe, but I just kind of have to think about what putting my stuff in there is gonna feel like for some of them. Coming back to LA with it is gonna be an interesting finale.

Klein: And a wonderful homecoming for you! One of the things you're mentioning with the grass piece though is that you’ve worked with growth, erosion, and weathering effects throughout your career. But grass is something that you’ve deployed in installations and there have been things in your projects that are beyond your control, right?

There are things that are subject to these natural processes. And so the show is called “Nature Never Loses.” To think about this point that you're raising here, we aren't outside of nature. There's often reasons why registrars don't like to have plants in the galleries because of infestations and insurance and all the things. But when I see an idea from you wanting to include these systems of growth and decay or organic materials in the spaces that are really supposed to be quite heavily controlled and staid, that to me is also rubbing up against these institutional systems, right? Thinking about the museum more as a laboratory or a greenhouse model is really different than the museum as a tomb or vault or something that implies stasis and collecting as opposed to process.

Cheng: I think you're right.

Klein: Since you were working on this for so long, I don't know how it evolved over time or how you narrowed it down to the direction that you ended up. This process for you, what was it like actually trying to bring the work inside and how did you feel about that?

Cheng: I just let it all happen in the past. To see it framed in a way that's understanding to a larger audience is nice. All the things I've tried to do and work on seem very natural to me, but it's not that natural to others to see this much work.

That's one of the things that concerns me all the time. Am I in the way of my own work? I'm trying to make it universal. Being at John Doe Company [the name he began working under in 1966] made it possible with people not knowing who that person was. But now I'm showing myself with it.

At my age, I can reflect on it differently. I can see myself in it without being tied to anything that says, “I can only do this or only do that.” Maybe I'm trying to take advantage of the fact that I'm not in the majority. I'm always gonna be marginal in a majority society because that's how it came out.

If I was in China and in the majority trying to say something I would have to think about that too. But because I’m not, it allows me a freedom that I've always enjoyed and taken advantage of. So I just have to deal with it and it's interesting in its own way. I'm Carl Cheng, John Doe Company. I’m one person, and yet I don't feel attached to one aspect of my work that I have to prove. It was always loose for me personally. Maybe getting it all together is a good thing in terms of what a human being is doing.

in your life?

in your life?