AGE: 30

BASED: New York

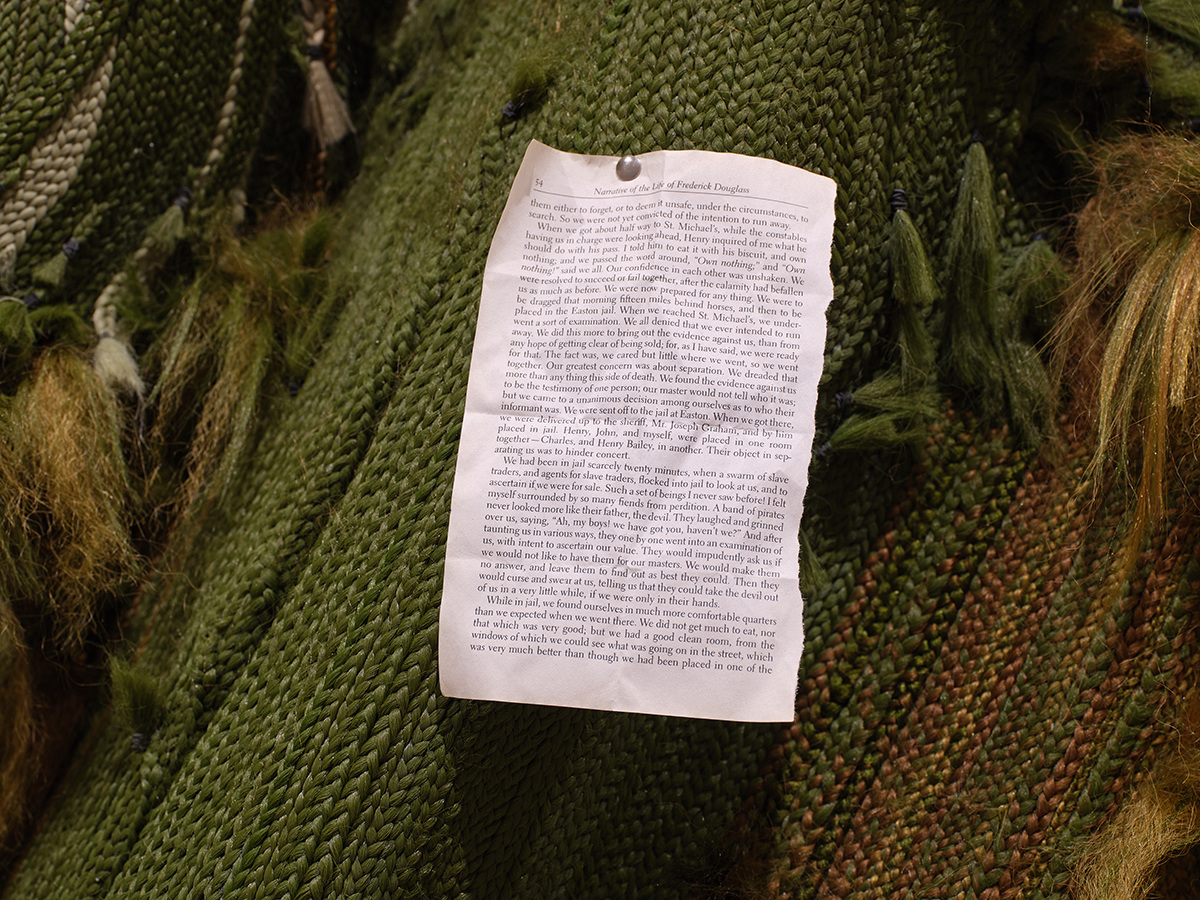

A hulking tree trunk spent the winter in one of MoMA PS1’s galleries this year. Measuring eight feet tall and assembled out of foam, cement, wood, and over 3,000 braids of synthetic hair, the sculpted relic was punctuated by a sonic tapestry of recordings that immerse visitors in moments of “Black convening.”

The installation was not a static sanctuary, but a continually evolving act of presence. When we met ahead of its unveiling, the artist behind the work, Malcolm Peacock, was already calling Five of them were hers and she carved shelters with windows into the backs of their skulls a milestone piece. The Raleigh, North Carolina–born, Baltimore-raised artist began work on the installation last January, a few months into a Studio Museum in Harlem residency that the PS1 showing concluded, pulling from research on redwoods he’d initiated after two summers spent in the Pacific Northwest. It is the only artwork he made in 2024.

Peacock is well aware that most young artists would be warned against dedicating close to a year to a single piece. “Not when you’re 30,” he tells me with a laugh. But that one-track mindset has paid off thus far.

“I have made six things in the last five or six years for various group exhibitions, and endurance has played an essential role in bringing these works to life,” Peacock reasons. The Studio Museum residency is just the latest in a round of institutional attention—including the 58th Carnegie International Fine Prize and a duo show with Shala Miller at Artists Space—that the interdisciplinary artist has garnered since earning his MFA at Rutgers University in 2019.

When asked where he thinks the next five years will take him, Peacock doesn’t blink an eye. “I just want to keep moving like this,” he says. “I would rather have a different career before I settle.” Refusing to settle, or to settle down—that daily dissent grounds Peacock’s practice. Whether he’s braiding, leading breathing exercises, or running while reciting an inner monologue, the artist is interested in making the experience of effort—and the (often invisible) barriers to accessing rest and recreation—manifest.

Malcolm Peacock, Five of them were hers and she carved shelters with windows into the backs of their skulls (Detail Shot), MoMA PS1, 2024. Photography by Kris Graves and courtesy of the artist and MoMA PS1.

One thing is certain: Working at the monumental scale the Studio Museum residency offered has inspired Peacock to meditate on the opportunities that making a major—in all senses of the term—work can afford an artist.

His next project will see him apply that macroscopic lens to a historical event: the first transcontinental American ultramarathon, where 199 men attempted to cross the country by foot in 1928. The artist will focus on the experiences of the five Black men who made the journey and their reverberations a century later.

“I’ll never forget how, in Nicole Miller’s To the Stars, Alonzo King says to his dance students, ‘The whole universe … wants to expand,’” Peacock notes, referring to the Los Angeles-based artist’s 2019 film. “Since completing Five of them were hers…, I’ve become excited about making more works that can speak to the notion of stretching what I know or believe I know to be possible. The word ‘possible’ can often be a barrier that is placed upon people. If there is a desire for agency in our lives, I think we must interrogate that word, its meaning, and its use.”

in your life?

in your life?