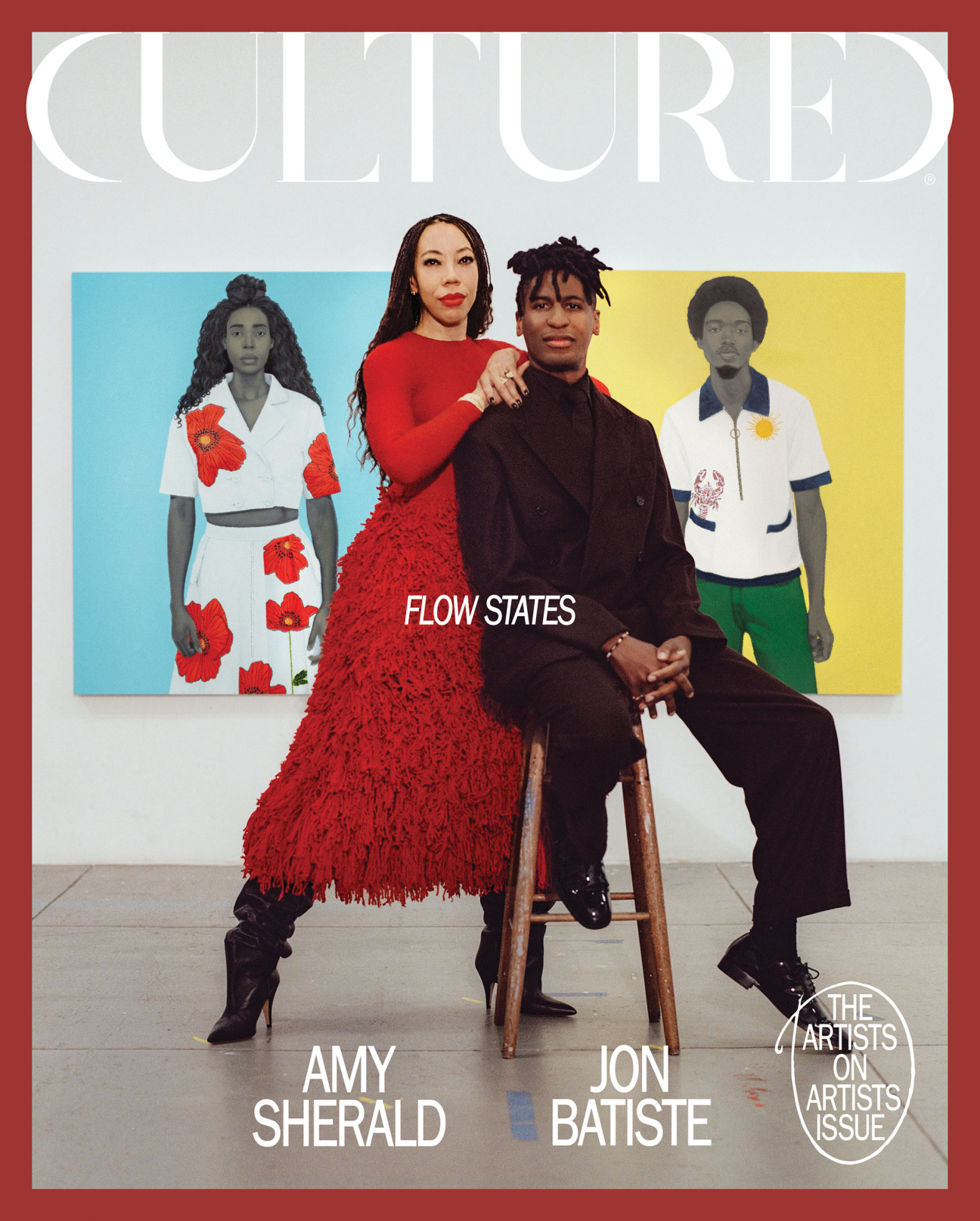

Pre-order the inaugural Artists on Artists issue, featuring this conversation, alongside others between Venus Williams and Titus Kaphar and Malcolm Washington and Njideka Akunyili Crosby, here.

When they step into their studios, Jon Batiste and Amy Sherald become vessels—channeling any number of inspirations, from Frida Kahlo and Beethoven to their own inner child. “When you’re in that flow state, sometimes you forget how you got to the end result,” says Batiste.

For the musician, this trance-like creative process has resulted in five Grammy awards, including Album of the Year for his 2021 project We Are. He’s also an Academy Award winner, thanks to his work on Pixar’s widely acclaimed Soul. Sherald, for her part, is revered for striking portraits—held in the permanent collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Smithsonian—in which her subjects, often rendered in grayscale, seem almost to vibrate with self-possession and conviction.

The pair was first introduced by a mutual friend: one of Sherald’s most well-known subjects, to whom she refers simply as “Michelle.” Sherald’s portrait of the former first lady earned her the grand prize in the 2016 Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition from the National Portrait Gallery—making her the first woman and first African American to do so—and its presence was partially credited with an annual increase of over 1 million visitors to the museum. This winter brings yet another accolade for the artist, with “American Sublime,” a mid-career survey and her largest exhibition yet, on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art before it heads to New York and DC next year. Batiste met the Obamas when they executive produced American Symphony, a documentary about the musician’s composition of the same name, which premiered at Carnegie Hall in 2022. This year marks a return to classical music for Batiste, whose latest album, Beethoven Blues, presents modern renditions of the canonical composer’s time-honored works, and was released just a day before the opening of Sherald’s exhibition.

Both Sherald and Batiste have grown accustomed to the complex privileges of being welcomed into spaces of power—the White House among them. Such experiences spur both artists to challenge notions of how Black art is perceived and how it’s celebrated. But despite their sweeping impacts on contemporary culture, both are careful to protect the delicate filament—that “pure thing”—at the heart of their work.

Here, the duo discusses how they keep that spark safe, and the complexities that come with “shaping our perception of history.”

Jon Batiste: Amy, you’re a genius. Genius is one of those things where I know it when I see it, but I don’t always understand it in other mediums. When I see your work, I’m like, “This is coming from somewhere deeper than just craft, technique, or conception.” There’s a level of divinity to it.

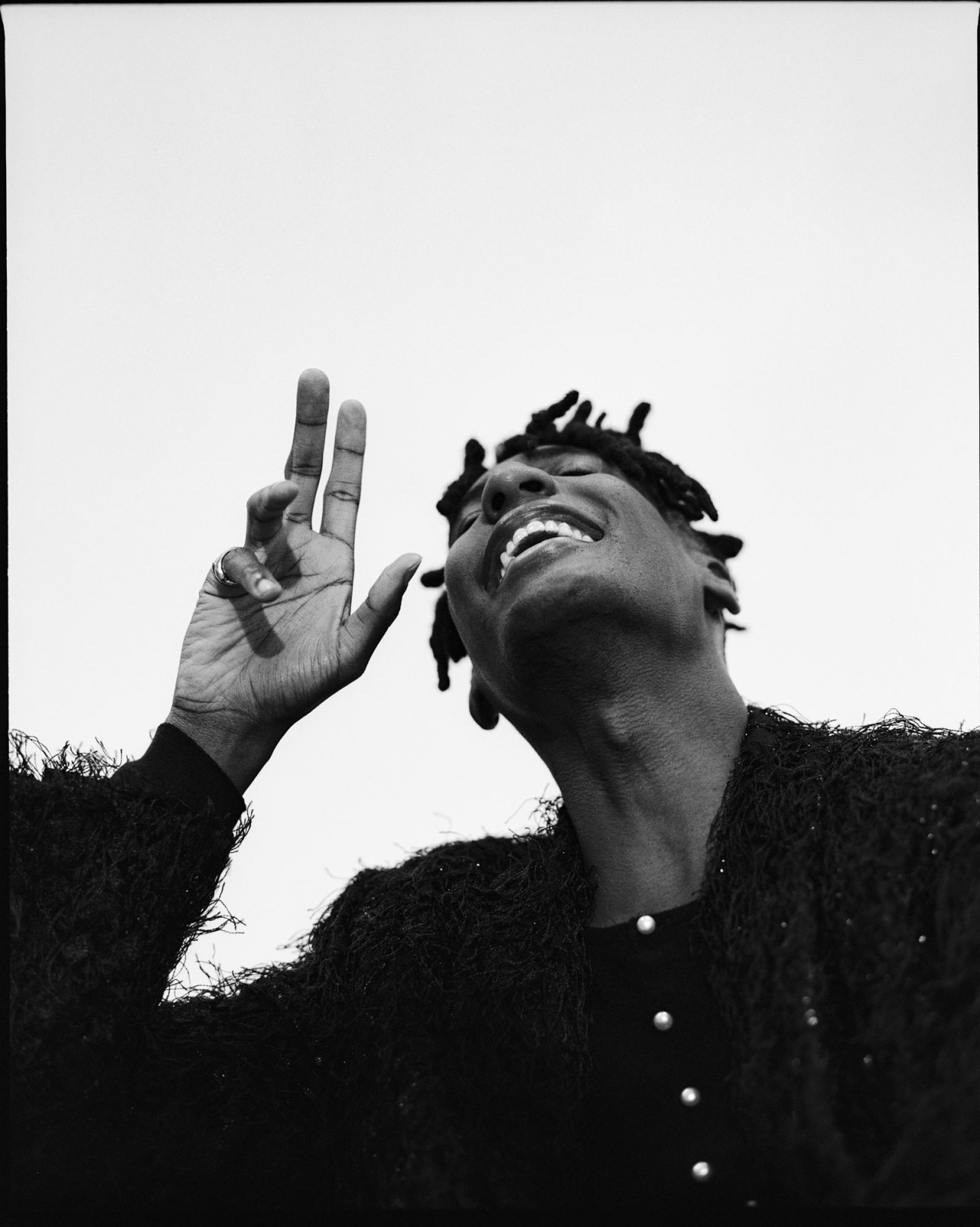

Amy Sherald: I felt the same when I watched you play. You never had to look down. Your eyes were closed, and it was coming from your body, your spirit, your soul.

Batiste: I feel like a vessel. I work hard to then be in the moment like a kid.

Sherald: Yeah, it’s like a trance. When I was younger, I used to have seances and invite Frida Kahlo because that’s who I felt like I was tapping into at the time. Then growing up, we couldn’t watch TV because of the church we attended, so we’d listen to jazz music. There’s this one song on [John] Coltrane’s A Love Supreme called “Pursuance.” When I heard that song, I knew how I wanted my work to be. It’s that psychic energy I try to transport into my portraits—what happens between me, the brush, the painting, and the model.

Batiste: That reciprocal emotional relationship is so deep, even with the audience. Their energy affects what I’m doing onstage. It’s almost like choosing the subject is part of the craft. How do you identify your subjects?

Sherald: It’s intuitive—I just rely on the universe. The ideas come, and I do what I’m told. What’s your earliest memory of seeing something that helped you envision your future? For me, it was a painting by an artist from my hometown [in Georgia], who was white but painted himself as a Black man. I’d never seen a painting of a Black person, period. That painting created a world from which I could imagine.

Batiste: That’s what I felt when I first heard music, believe it or not, in video games. I grew up in New Orleans; I was soaking up this incredible cultural inheritance—all the sounds and rhythms of the city. But as a kid who was introverted and shy—not a performer—video games allowed me to go into the world of characters, to role-play. They awakened my creative instinct in a different sense, like, Wow, we can create things, we can mold the environment around us, and that then inspires others to do the same thing in their way. That opened up something that eventually led back to the music that I was soaking up in the classical world.

Sherald: How did that shift for you when you became successful? I’m also an introvert, and there’s a different person that has to exist in the world than the Amy that wakes up at home. How do you protect your energy?

Batiste: It’s that inner child, the pure thing we have within us. That’s the creative instinct. If I can find a way to get back to that, I know that I’m okay. Sometimes that means taking six months off to journey back there. But whatever it takes, as long as I know that I can identify that place within, I know that I can make it manifest. It’s about cultivating a space where, every time you step into this studio or go to the top of this mountain, that sacred creative energy is there. Do you have a place like that?

Sherald: I want to say it’s my studio, but it changes as your career changes. I’m producing a lot more work now, so that feels different. These days, it’s more what I find in nature, and then I carry that feeling back to the studio. When I’m painting, my tentacles are so extended that I can feel too much, and that distracts me from working. I need to feel cocooned to work—like how dogs wear tight vests when they’re scared of thunder—to be in my body and to start the process. That’s hard to do if you’re collaborating with a group of people.

Batiste: It takes acute, direct communication. When you’re in dialogue with yourself, there’s so much shorthand. Translating that to someone else can disrupt it. I’ve learned that I have to have two me’s. I collaborate with a lot of folks, but I’m also trying to take something that nobody sees or hears and make it tangible. How do I transfer the feeling of this sound I want us to co-create together? There are no words for it—it’s another language. Certain people you have chemistry with, and certain people will never understand the space you need to get into.

Sherald: The people around me have to be aligned. I need “glass half-full” people. The word “impossible” doesn’t exist for me. It’s like, This didn’t work today because something else is going to come that’s going to be even better tomorrow. I love it when things don’t work; it leaves room for something else that’s going to happen next. I live my whole life that way.

Batiste: It’s about living life where even the mundane becomes the muse. There’s a peace in that—it’s like constant meditation or prayer. You’re always seeking.

Sherald: So you and I met for the first time four months ago in Ojai. You were introducing our mutual friend Michelle [Obama].

Batiste: I loved what you did for that official portrait—you’re shaping our perception of history. It’s a lot to manage, being Black—first off, in terms of navigating creative output and representing something so important on many levels. We’re often the first or only ones in the room, and many times there’s no blueprint for that. How did you approach a project like that?

Sherald: I went about it like I do everything else. The formula is what got me here. I’ve learned to trust myself. The most important part of any artist’s practice is intuition: knowing when to listen to yourself and not overstepping yourself. At that point in my career, I thought, I’m just going to move through this like a white man. But now I’d say, I’m moving through the world like a Black woman. I didn’t survive a heart transplant for me not to get this. When I left the White House, I was certain that this was mine, and I survived to get this opportunity.

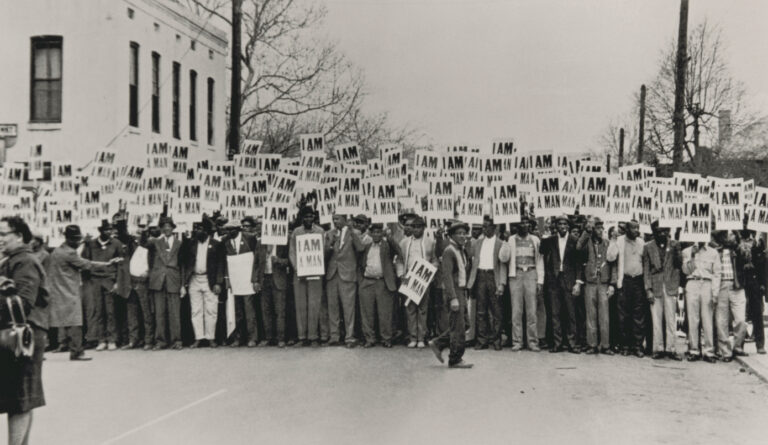

Batiste: That reminds me of when I first played at the White House. I brought my whole family; that was a prerequisite. My grandfather was 92 or 93 at the time, and his perspective on what was happening was incredible. He was in the first wave to integrate the Navy, he participated in the sanitation strikes with Dr. King, he was the hotel workers’ congress president. I’m a part of that lineage, and I got to see that moment through his eyes. To play classical music in my own way, with him in the White House, was really something—and to see that for my nephew, who was 6, some things are commonplace.

Sherald: My niece grew up with Barack [Obama] as president, and to her, having a Black man serve as the president of the United States was no big deal. It changes how they move in the world. We came from a generation where it was more like, We’ve come this far, we don’t want to make any trouble.

Batiste: And this generation is like, This is not enough. Where that will go culturally is exciting to watch.

Sherald: Well, they have so many examples. Maybe if you were playing the piano when I was playing the piano, I would have thought to myself, I can do this. But I didn’t see a connection there the way I found in painting, or in photography. With this new album, you’re painting a portrait of Beethoven and marrying that with a portrait of yourself, which is thrilling to listen to. It’s such a natural transition. How did you decide where to start?

Batiste: The starting point was learning the score as if I were a classical pianist. But I’ve always heard it the way I play it now. It’s natural for me, given my lineage and lived experiences. Beethoven composed this music centuries ago, but now there’s so much diasporic genius that has emerged. We haven’t heard recordings of how he would play it now. That’s the purpose of music—not to be locked in amber in a history museum, but to be extended and refined. It’s like we’re in conversation.

Sherald: What’s a typical day like when you’re not working?

Batiste: I try to live a life in the embrace of peace.

Sherald: When I’m out of the studio, I don’t like to think about the studio. If I’m traveling, I may not even want to go into a museum. I want to do something else because it will give me something else.

Batiste: You have to let those downloads pull you back to the craft. How do we get more life? How do we work on the human being part? How do you work on your humanity? Because that’s what ultimately makes the work.

Sherald: Through giving. I’ve been a caregiver for multiple family members, and that always keeps me grounded. At one point, I taught art to inmates in Baltimore City jail. They had never been told to play, ever. Giving them the space to create, to express themselves, was new for them. It created vulnerabilities they weren’t used to. My dogs also keep me grounded. I just heard [the musician] Adele say, “I’m going to retire; you guys aren’t going to see me for a while because I need to go live the life I’ve built.” I feel that way a little bit. I’m not that far along in my career but the spiritual lift of it is a lot. Somewhere, you have to find a balance.

Batiste: After the survey you’re presenting…

Sherald: You might find me on an island somewhere!

Batiste: I’ll be right down there with you.

Hair by Myss Monique for Amy Sherald and Jenna Robinson for Jon Batiste

Makeup by Laramie With Day One for Sherald and Jesse Lindholm for Batiste

Production by Dionne Cochrane

Styling Assistance by Cecilia Lizarraga for Sherald

Styling Assistance by Kyle Nelson, Wilton White, and Ron Jeffries for Batiste

Production Assistance by Brittany Thompson

in your life?

in your life?